The Reenchantment of the World (20 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

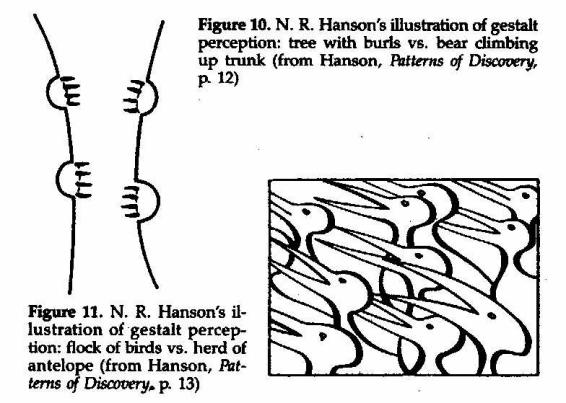

a tree trunk with burls on it? Do you see a flock of birds in Figure 11,

or a herd of antelope? Would people who had never seen antelope, but only

birds, be able to regard Figure 11 as a picture of antelope? Polanyi's

general point is that at a very early age we learn, or are trained,

to put reality together in certain ways ("figurate" it, in Barfield's

terminology), and that the indoctrination is not merely cultural but also

biological. Thus on a conscious level we largely spend our lives finding

out what we already know on an unconscious level. Alternative realities

are screened out by a process that the American psychiatrist Harry Stack

Sullivan used to call "selective inattention," and which has since been

relabeled "cognitive dissonance." Thus "antelope" people would presumably

find "bird" people incomprehensible. Any articulated world view, in fact,

is the result of unconscious factors that have been culturally filtered

and influenced, and is thus to some extent radically disparate from any

other world view.

of seeing. Polanyi points out that the scientist learns his craft in

the same way a child learns a language. Children are born polyglots:

they naturally have German gutterals, French nasaIs, Russian palatals,

and Chinese tonals. They cannot remain this way for long, however,

for to learn a particular language is simultaneously to unlearn the

sounds not common to that language. English, for example, does not have

the Russian palatal sound, and the English-speaking child ultimately

loses the ability to pronounce words in a genuinely Russian manner. The

awareness here is subsidiary, or even subliminal. As in bicyde riding,

so in speaking, we learn to do something without actually analyzing or

realizing what it is we are learning. Science has similarly an ineffable

basis; it too is picked up by osmosis.6

experience, is that of the study of X-ray pathology, and is worth quoting

in full.

X-ray diagnosis of pulmonary diseases. He watches in a darkened room

shadowy traces on a fluorescent screen placed against a patients

chest, and hears the radiologist commenting to his assistants, in

technical language, on the significant features of these shadows. At

first the student is completely puzzled. For he can see in the

X-ray picture of a chest only the shadows of the heart and ribs,

with a few spidery blotches between them. The experts seem to be

romancing about figments of their imagination; he can see nothing

that they are talking about. Then as he goes on listening for a few

weeks, looking carefully at ever new pictures of different cases,

a tentative understanding will dawn on him; he will gradually

forget about the ribs and begin to see the lungs. And eventually,

if he perseveres intelligently, a rich panorama of significant

details will be revealed to him: of physiological variations and

pathological changes, of scars, of chronic infections and signs

of acute disease. He has entered a new world. He still sees only a

fraction of what the experts can see, but the pictures are definitely

making sense now and so do most of the comments made on them. He is

about to grasp what he is being taught; it has clicked.7

not really rational but existential, a groping in the dark after the

fall through Alice's rabbit hole has occurred. There is no

logic

of

scientific discovery here, but rather an act of faith that the process

will lead to learning, and on the basis of the students commitment,

it does.

process violates the Platonic/Western model of knowledge, which insists

that knowledge is obtained in the act of distancing oneself from the

experience. Our hypothetical medical student knew absolutely nothing

when he stood outside the procedures. Only with his submergence in the

experience did the photographs begin to take on any meaning at all. As he

forgot about himself, as the independent "knower" dissolved into the X-ray

blotches, he found that they began to appear meaningful. The crux of such

learning is the Greek concept of 'mimesis,' of visceral/poetic/erotic

identification. Even from Polanyi's verbal description, we can almost

touch the willowy blotches on the warm negative, smell the photographic

developer in the nearby darkroom. This knowledge was clearly participated.

after

the

knowledge has been obtained viscerally. Once the terrain is familiar,

we reflect on how we got the facts and establish the methodological

categories. But these categories emerge from a tacit network, a process

of gradual comprehension so basic that they are not recognized as

"categories." As Marshall McLuhan once remarked, water is the last thing

a fish would identify as part of its environment, if it could talk. In

fact, the categories start to blur with the learning process itself;

they become "Reality," and the fact that the existence of other realities

may be as possible as the existence of other languages usually escapes

our notice. The reality system of any society is thus generated by an

unconscious biological and social process in which the learners in that

society are immersed. These circumstances, says Polanyi, demonstrate

"the pervasive participation of the knowing person in the act of knowing

by virtue of an art which is essentially inarticulate." I can speak of

this knowledge, but I cannot do so adequately.8

is a contradiction in terms. He argues that all knowing takes place in

terms of meaning, and thus that the knower is implicated in the known. To

this I would add that what constitutes knowledge is therefore merely the

findings of an agreed-upon methodology, and the facts that science finds

are merely that -- facts that

science

finds; they possess no meaning

in and of themselves. Science is generated from the tacit knowing and

subsidiary awareness peculiar to Western culture, and it proceeds to

construct the world in those particular terms. If it is true that we

create our reality, it is nevertheless a creation that proceeds in

accordance with very definite rules -- rules that are largely hidden

from conscious view.

of the X-ray student would suggest. To see this, let us follow Barfield

and define 'figuration' as representation, that is, the act by which we

transform sensations into mental pictures.9 The process of thinking

about these "things," these images, and their relationships with each

other (a process commonly called conceptualization) can be defined as

'alpha-thinking.' In the process of learning, figuration gradually becomes

alpha-thinking in other words, our concepts are really habits. Our X-ray

student at first formed mental pictures of the blotches or shadows

on the screen, then learned to identify cancer and tuberculosis. His

instructors, however, immediately and unthinkingly saw cancer and TB

without experiencing the blotches in the same way he did. Similarly,

when I hear a bird singing, I form some sort of mental image of the

sound and try to sort it out. My friend, a professional ornithologist,

goes through no such process. He hardly even hears the notes. What

comes to his mind, quite automatically, is "thrush." Thus, at least in

his professional capacity, he is doing alpha-thinking all the time. He

is beyond figuration, whereas I am still struggling with it. It would

be more correct to say that he figurates in terms of concepts rather

than sensations and primary data. He does, then, participate the world

(or at least the bird world), but for the most part as a collection

of abstractions.

system, we are all ornithologists. We experience an agreed-upon set of

alpha-thoughts, or what Talcott Parsons calls "glosses," instead of the

actual events. In short, we continue the process of figuration which

began in the learning stages, but it becomes automatic and conceptual

rather than dynamic and concrete.

"Concepts of Science." Let us say that you and I are sitting on the steps

of an old farmhouse in the country one summer night, looking down the

dusty road that leads to the house. As we sit there, we see a pair of

headlights coming up the road. Having nothing more profound on my mind at

the moment, I turn to you and say, "There's a car coming up the road." You

are silent for a moment and then ask me, "How do you know its a car? After

all, it could be two motorcycles riding side by side." I reflect on this,

and then decide to modify my original statement. "You're right. Either

there's a car coming up the road, or two motorcycles riding side by

side at the same speed." "Hold on," you reply. "That's not necessarily

the case either. It could be two large bunches of fireflies." At this

point, I may wish to draw the line. We could, after all, do this all

night. The point is that in our culture, two parallel lights moving at

the same speed along a road at night invariably denote an automobile. We

do not really experience (figurate) the lights in any detail; instead

we figurate the concept "car." Only an infant (or a poet, or a painter)

might figurate the experience in the rich possibility of its detail;

only a student figurates X-ray images.10 Every culture, every subculture

(ornithology, X-ray pathology) has a network of such alpha-thoughts,

because if we had to figurate everything, we would never be able to

construct a science, nor any model of reality. But such a network is a

model

, and we tend to forget that. In Alfred Korzybski's famous dictum

(

Science and Sanity

, 1933), "the map is not the territory." After all,

what if the lights

were

fireflies?11

nonparticipating consciousness. Alpha-thinking necessarily involves the

absence of participation, for when we think about anything (except in

the initial stages of learning) we are aware of our detachment from the

thing thought about. "The history of alpha-thinking," writes Barfield,

"accordingly includes the history of science, as the term has hitherto

been understood, and reaches its culmination in a system of thought

which only interests itself in phenomena to the extent that they can be

grasped as independent of consciousness."

perception was precisely the historical project of the Jews and the

Greeks. The Scientific Revolution was the final step in the process,

and henceforth all representations in the Western reality system became

what Barfield calls "mechanomorphic." Construing reality mechanically

is, however, a way of participating the world, but it is a very strange

way, because our reality system officially denies that participation

exists. What then happens? It ceases to be conscious because we no longer

attend to it, writes Barfield, but it does not cease to exist. It does,

however, cease to be what we have called original participation. Making

an abstraction out of nature is a particular way of participating

it. Just as the ex-lovers who refuse to have anything to do with one

another really have a powerful type of relationship, so the insistence

that subject and object are radically disparate is merely another way

of relating the two. The problem, the strangeness, lies in the denial

of participation's role, not only because the learning process itself

necessarily involves mimesis, but because as long as there is a human

mind, there will be tacit knowing and subliminal awareness.

in alpha-thinking as much as we are. Once past his apprenticeship, the

witch doctor spends much of his time identifying the various members of

the spirit world according to a formula. Despite this, the "primitive"

slides quite naturally between figuration and alpha-thinking, or in

our terminology, between the unconscious and the conscious mind;

and he probably spends most of his time experiencing, rather than

abstracting. Even if he wished to shut the unconscious out, it would

not be possible, because for him the spirits are real and (despite

any ritualized system) frequently experienced on a visceral level. His

experience of nature constantly creates joy, anxiety, or some intermediate

bodily reaction; it is never a strictly cerebral process. He may often

be frightened by his environment or by things in it, but he is never

alienated by it. There are no Sartres or Kafkas in such cultures any more

than there were in medieval Europe. The "primitive" is thus in touch

with what Kant called the 'Ding an sich,' the thing in itself, in the

same way as was the denizen of ancient Greece or (to a lesser extent)

medieval Europe. We, on the other hand, by denying both the existence

of spirits and the role of our own spirit in our figuration of reality,

are out of touch with it. Yet it is the case, as Barfield notes; that in

Other books

April Fool Bride by Joan Reeves

In Bed With A Stranger by Mary Wine

Until There Was You by Higgins, Kristan

Atone by Beth Yarnall

Bond of Fate by Jane Corrie

Donovan Creed 11 - Because We Can! by John Locke

Obsession (Endurance) by McClendon, Shayne

A Deadly Affair at Bobtail Ridge by Terry Shames

If Looks Could Kill by Carolyn Keene