The Reenchantment of the World (15 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

philosophy

about how the universe worked. Magic was. Of

course, there were many types of magic and many magical philosophies,

but all of them, in sharp contrast to church Aristotelianism, urged the

practitioner to operate on nature, to alter it, not to remain passive. In

this sense, then, the ascendancy of magical doctrines and techniques

in the sixteenth century was fully congruent with the early phases

of capitalism, and Keith Thomas has recorded (for England, at least)

how extensive and intense occult activity was during this time.44 The

idea of dominating nature arose from the magical tradition, perhaps the

first explicit statement of the notion occurring in a work by Francesco

Giorgio in 1525 ("De Harmonia Mundi"), which is not about technology,

but -- of all things -- numerology. This art, he says, will confer upon

man as regards his environment 'vis operandi et dominandi,' "the power

of operating and dominating." We should not be surprised that, in the

sixteenth century, this concept was easily extended from numerology to

accounting and engineering.

between the esoteric and exoteric traditions of the occult sciences. At

the heart of the cabala, for example, lay the notion of a "dialing

code." In the Hebrew alphabet, letters are also numbers, and hence an

equivalence can be established between totally unrelated words based on

the fact that they "add up" to the same amount. The right combination,

it was believed, would put the adept in contact with God. Pico della

Mirandola, for example, was fascinated by the mystical ecstasy brought on

by number meditation, a trance in which communication with the Divinity

was said to occur (the meditation could, of course, produce such ecstasy

if the activity narrowed one's attention in a yogic fashion).45 At the

same time, similar techniques formed the basis of a practical cabala

that the adept might use to obtain love, wealth, influence, and so on.

century, pursuit of God or world harmony began to seem increasingly

quaint, and emphasis on the practical or exoteric tradition resulted in

a purely representational use of the Hebrew alphabet. We can see this

shift in books published only a decade apart by Robert Fludd and Joseph

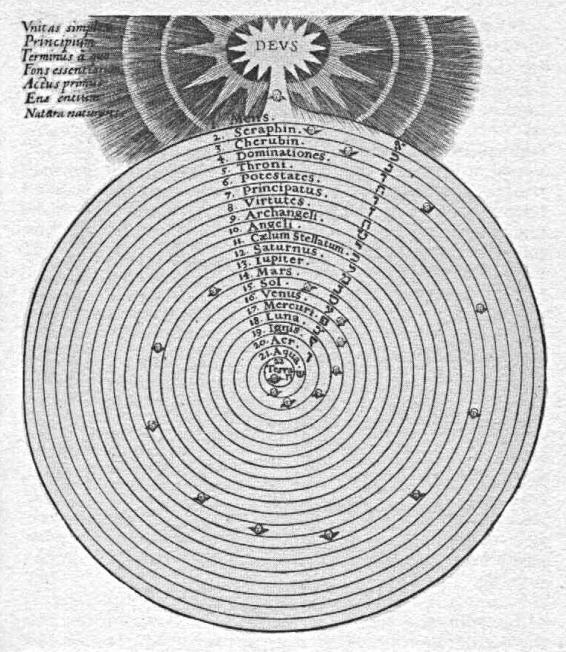

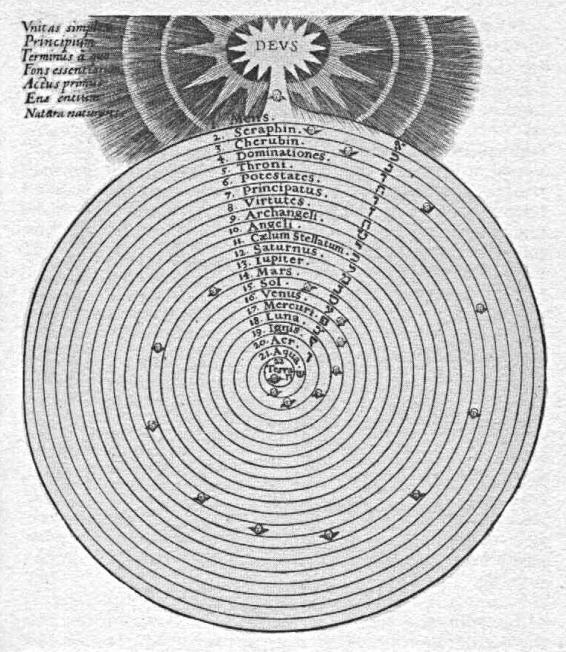

Solomon Delmedigo. In Plate 9, Fludd's illustration of the Ptolemaic

universe (1619), the Hebrew letters signify the "spiritual intelligences"

that rule each of the twenty-two spheres, from the World Mind, ("Mens")

down to the sphere of the earth. (This same type of labeling also occurs

in cabalistic illustrations of the human body, where Hebrew letters

serve to identify the spiritual intelligences that govern each particular

part.) Fludd was a major proponent of the view that the Hebrew letters in

the diagram corresponded to something real: they concretely identified the

ruling archetypes of each region, and this information could be plugged

into certain types of cabalistic "equations" to generate significant

results for the practitioner. It was hardly a problem that the letters

did not correspond to anything material or substantial in in nature.

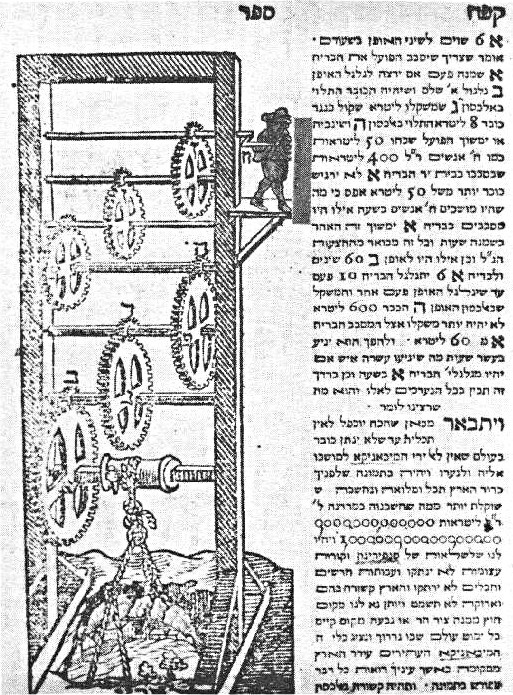

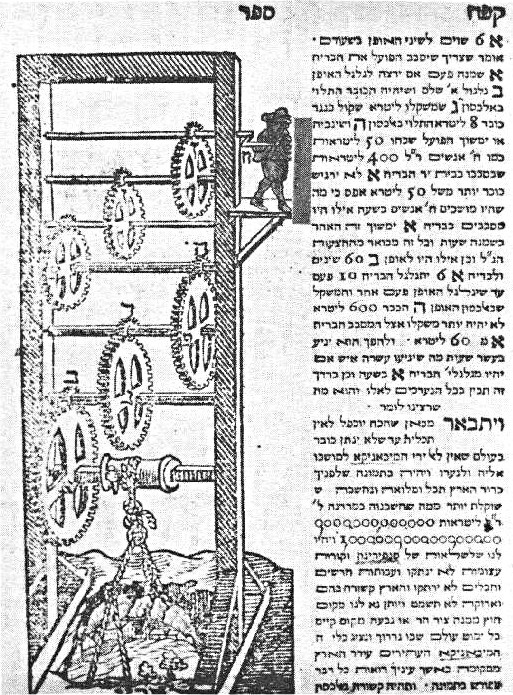

an engineering sketch from Joseph Solomon Delmedigo's book "Elim"

(1629). Here, the letters are used to label a set of gears in a diagram

illustrating how power can be multiplied so that, in Archimedean fashion,

an individual with a place to stand can move a large section of the

earth. It is no accident that Rabbi Delmedigo had been a student of

Galileo at Padua, that he was an ardent Copernican, the first Jewish

scholar to employ logarithms, and ultimately a leading popularizer

of scientific knowledge. Yet the labels have a still more complex

significance. "Elim" means "powers" or "forces," and its implication can

be both sacred and secular. Thus Jehovah is addressed as "El" in Hebrew

liturgy; and more generally, an "el" can be a power that carries the

essence ("spiritual intelligence") of God. But "el" can signify a purely

material force as well, such as the power developed by a gear train. This

ambiguity is reflected in the book itself, which deals with both religious

and scientific matters, and in the authors attitude toward the cabala

-- an attitude that was so ambiguous that present-day Jewish scholars

remain uncertain whether Delmedigo was a critic or a proponent. For a

time, then, disparate concepts of number could exist side by side, even

within a single mind, but ultimately, the esoteric tradition was unable

to sustain itself. Under the pressures of a new economy, the spiritual

aspect of the cabala, along with the evocative power of the spoken Hebrew

word, became increasingly irrelevant. It was not that the cabala was

"wrong," but that technology and mercantile capital had little use for

religious mathematics.46

sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, with the possible exception

of witchcraft, which was (to my knowledge) purely transitive and without

a subjective, or self-transforming, aspect. What science accomplished

(or rather, what became science) was the adoption of the epistemological

framework, indeed the whole ideology, of the exoteric tradition. All

of the "natural magicians" of the sixteenth century, such as Agrippa,

Della Porta, Campanella, John Dee, and Paracelsus, right down to Francis

Bacon, drew on both the technological and Hermetic traditions for the

phrase "evoking the powers of nature." Both traditions began to fuse at

this time and form the basis of modern scientific experimentation. Both

were active ways of addressing reality, constituting a sharp contrast to

the static nature of Greek science and the frozen verbalism of medieval

Scholastic disputation. The identity of knowledge and construction which

we discussed in Chapter 2, the "making that is itself a knowledge," which

received its clearest expression in the work of Bacon, was derived from

the numerous writings on magic and alchemy which appeared in Europe during

the sixteenth century.47 Della Porta candidly termed magic the "practical

part of natural science," and such men as Dee, Campanella, and Agrippa

tended to blur (from our point of view) control of the environment by

means of the art of navigation with control of the environment by means

of astrology.48 Prior to and during the English Civil War, remarked

John Aubrey in "Brief Lives," "astrologer, mathematician, and conjurer

were accounted the same things."49 It was only after magic had provided

technology with a methodological program that the latter was in a position

to reject the former. But it was more in the fusion of the two, than in

their subsequent separation, that the esoteric tradition was lost.

in astrology, for example, as represented by the Florentine scholar

Marsilio Ficino (1433-99), who translated the entire Hermetic corpus for

Cosimo de Medici between 1462 and 1484, sought to condition the body and

spirit through music or incantation in order to alter the personality

("receive the celestial influence"). Bacon himself approved of this

aspect of the art, calling it "astrologia sana," and D.P. Walker has in

effect said the same thing when he calls Ficino's system "astrological

psychotherapy."50 But the ultimate legacy of the tradition, even among

present-day astrologers who consider themselves serious students, is for

the most part manipulative and this-worldly, and the horoscope column

in the daily newspapers represents the pathetic outcome of what was once

a magnificent edifice of dialectical thought.

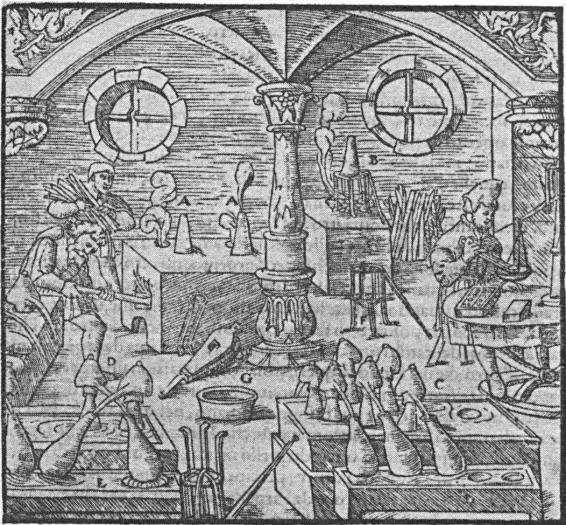

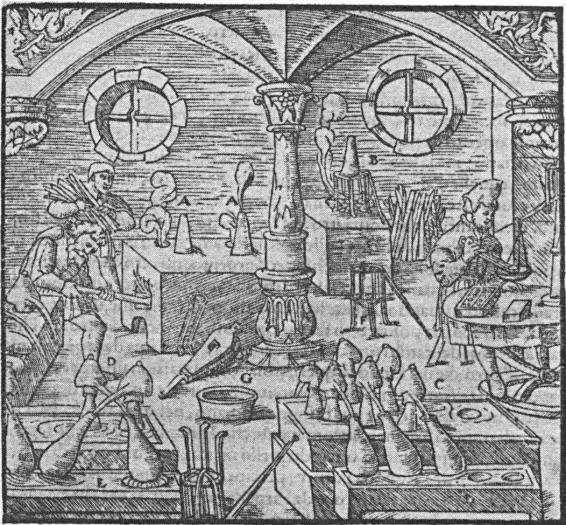

were once again technological, particularly because of alchemy's

age-old relationship to mining, metallurgy, and numerous crafts and

manufacturers. The sixteenth century saw the emergence of a coterie of

artisans who denounced the alchemists, this attitude being most clearly

expressed in works such as Biringuccio's "Pirotechnia" and Agricola's

"De Re Metallica."51 The split is at the same time a response to

changing economic relationships, in particular, the collapse of the

guilds. An increasingly laissez-faire economy challenged both the

feudal notion of maintaining secrecy about a craft's techniques and

the oral tradition that had been the basis of initiation into these

"mysteries." Pressure to reveal these secrets, to make them accessible

to all by way of Gutenberg's movable type, led to the publication of

craft handbooks (like those of Biringuccio and Agricola) which provided

detailed accounts of processes and illustrations of guild practices

(see Plate 11). These works, the appearance of which would have been

viewed with horror in the Middle Ages, now served the interests of a

large and amorphous social class. Craft processes themselves had become

commodities; and secrecy, revealed knowledge, and microcosm/macrocosm

analogies were seen as superfluous and even inimical by an artisanry that

was increasingly caught up in a market economy. Thus, when the surgeon

Ambroise Paré (1510-90) was accused of having betrayed guild secrets,

he felt confident in replying that he was not of those men who "make a

cabala of art."52 Indeed, the whole notion of scientific organization

which was trumpeted by Bacon in the "New Atlantis" was completely

incompatible with the medieval ideal of deliberate secretiveness.

the idea of an inner psychic landscape (in our terms), or original

participation, was partly lost, technology was able to judge the

alchemical tradition from the point of view of technical clarity and

precision and, of course, find it sorely lacking. As we have seen, the

language of alchemy is dreamlike, symbolic, imagistic, but this world

of resemblance was disintegrating. Carrots were not bottles, lions no

longer devoured the sun, androgynes were inventions in the same category

as unicorns. Cryptic phrases such as "the sun and his shadow complete

the work" did not glaze pots or extract tin, and names for substances

such as "butter of antimony" or "flowers of arsenic" (which, however,

lasted down to the late eighteenth century) were now seen as cumbersome

and inefficient. The whole alchemical imagery of things being themselves

and their opposites, or possessing inherent ambiguity, was now regarded

as stupid, incomprehensible, an obstacle to be rooted out. Biringuccio,

Bacon, Agricola, Lazarus Ercker, and many others deliberately set

themselves against the tradition of wonder at nature, of credulity

about fabulous beasts and plants and stones -- a tradition that had

characterized medieval literature from Pliny to Agrippa. The notion of

'satsang' still present in esoteric disciplines like Zen and yoga,

that the truth is miraculously communicable through a relationship

with a teacher, was an anathema to these men, who correctly saw that

the attempted domination of nature depended on cognitive clarity. The

collapse of an ecological, or holistic, orientation toward nature went

hand in hand with the rejection of dialectical reason.53

about how the universe worked. Magic was. Of

course, there were many types of magic and many magical philosophies,

but all of them, in sharp contrast to church Aristotelianism, urged the

practitioner to operate on nature, to alter it, not to remain passive. In

this sense, then, the ascendancy of magical doctrines and techniques

in the sixteenth century was fully congruent with the early phases

of capitalism, and Keith Thomas has recorded (for England, at least)

how extensive and intense occult activity was during this time.44 The

idea of dominating nature arose from the magical tradition, perhaps the

first explicit statement of the notion occurring in a work by Francesco

Giorgio in 1525 ("De Harmonia Mundi"), which is not about technology,

but -- of all things -- numerology. This art, he says, will confer upon

man as regards his environment 'vis operandi et dominandi,' "the power

of operating and dominating." We should not be surprised that, in the

sixteenth century, this concept was easily extended from numerology to

accounting and engineering.

between the esoteric and exoteric traditions of the occult sciences. At

the heart of the cabala, for example, lay the notion of a "dialing

code." In the Hebrew alphabet, letters are also numbers, and hence an

equivalence can be established between totally unrelated words based on

the fact that they "add up" to the same amount. The right combination,

it was believed, would put the adept in contact with God. Pico della

Mirandola, for example, was fascinated by the mystical ecstasy brought on

by number meditation, a trance in which communication with the Divinity

was said to occur (the meditation could, of course, produce such ecstasy

if the activity narrowed one's attention in a yogic fashion).45 At the

same time, similar techniques formed the basis of a practical cabala

that the adept might use to obtain love, wealth, influence, and so on.

Plate 9. The Ptolemaic universe according to Robert Fludd, 1619. Courtesy,

The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

century, pursuit of God or world harmony began to seem increasingly

quaint, and emphasis on the practical or exoteric tradition resulted in

a purely representational use of the Hebrew alphabet. We can see this

shift in books published only a decade apart by Robert Fludd and Joseph

Solomon Delmedigo. In Plate 9, Fludd's illustration of the Ptolemaic

universe (1619), the Hebrew letters signify the "spiritual intelligences"

that rule each of the twenty-two spheres, from the World Mind, ("Mens")

down to the sphere of the earth. (This same type of labeling also occurs

in cabalistic illustrations of the human body, where Hebrew letters

serve to identify the spiritual intelligences that govern each particular

part.) Fludd was a major proponent of the view that the Hebrew letters in

the diagram corresponded to something real: they concretely identified the

ruling archetypes of each region, and this information could be plugged

into certain types of cabalistic "equations" to generate significant

results for the practitioner. It was hardly a problem that the letters

did not correspond to anything material or substantial in in nature.

Plate 10. Engineering illustration from "Elim," by Joseph Solomon

Delmedigo, 1629.

an engineering sketch from Joseph Solomon Delmedigo's book "Elim"

(1629). Here, the letters are used to label a set of gears in a diagram

illustrating how power can be multiplied so that, in Archimedean fashion,

an individual with a place to stand can move a large section of the

earth. It is no accident that Rabbi Delmedigo had been a student of

Galileo at Padua, that he was an ardent Copernican, the first Jewish

scholar to employ logarithms, and ultimately a leading popularizer

of scientific knowledge. Yet the labels have a still more complex

significance. "Elim" means "powers" or "forces," and its implication can

be both sacred and secular. Thus Jehovah is addressed as "El" in Hebrew

liturgy; and more generally, an "el" can be a power that carries the

essence ("spiritual intelligence") of God. But "el" can signify a purely

material force as well, such as the power developed by a gear train. This

ambiguity is reflected in the book itself, which deals with both religious

and scientific matters, and in the authors attitude toward the cabala

-- an attitude that was so ambiguous that present-day Jewish scholars

remain uncertain whether Delmedigo was a critic or a proponent. For a

time, then, disparate concepts of number could exist side by side, even

within a single mind, but ultimately, the esoteric tradition was unable

to sustain itself. Under the pressures of a new economy, the spiritual

aspect of the cabala, along with the evocative power of the spoken Hebrew

word, became increasingly irrelevant. It was not that the cabala was

"wrong," but that technology and mercantile capital had little use for

religious mathematics.46

sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, with the possible exception

of witchcraft, which was (to my knowledge) purely transitive and without

a subjective, or self-transforming, aspect. What science accomplished

(or rather, what became science) was the adoption of the epistemological

framework, indeed the whole ideology, of the exoteric tradition. All

of the "natural magicians" of the sixteenth century, such as Agrippa,

Della Porta, Campanella, John Dee, and Paracelsus, right down to Francis

Bacon, drew on both the technological and Hermetic traditions for the

phrase "evoking the powers of nature." Both traditions began to fuse at

this time and form the basis of modern scientific experimentation. Both

were active ways of addressing reality, constituting a sharp contrast to

the static nature of Greek science and the frozen verbalism of medieval

Scholastic disputation. The identity of knowledge and construction which

we discussed in Chapter 2, the "making that is itself a knowledge," which

received its clearest expression in the work of Bacon, was derived from

the numerous writings on magic and alchemy which appeared in Europe during

the sixteenth century.47 Della Porta candidly termed magic the "practical

part of natural science," and such men as Dee, Campanella, and Agrippa

tended to blur (from our point of view) control of the environment by

means of the art of navigation with control of the environment by means

of astrology.48 Prior to and during the English Civil War, remarked

John Aubrey in "Brief Lives," "astrologer, mathematician, and conjurer

were accounted the same things."49 It was only after magic had provided

technology with a methodological program that the latter was in a position

to reject the former. But it was more in the fusion of the two, than in

their subsequent separation, that the esoteric tradition was lost.

in astrology, for example, as represented by the Florentine scholar

Marsilio Ficino (1433-99), who translated the entire Hermetic corpus for

Cosimo de Medici between 1462 and 1484, sought to condition the body and

spirit through music or incantation in order to alter the personality

("receive the celestial influence"). Bacon himself approved of this

aspect of the art, calling it "astrologia sana," and D.P. Walker has in

effect said the same thing when he calls Ficino's system "astrological

psychotherapy."50 But the ultimate legacy of the tradition, even among

present-day astrologers who consider themselves serious students, is for

the most part manipulative and this-worldly, and the horoscope column

in the daily newspapers represents the pathetic outcome of what was once

a magnificent edifice of dialectical thought.

were once again technological, particularly because of alchemy's

age-old relationship to mining, metallurgy, and numerous crafts and

manufacturers. The sixteenth century saw the emergence of a coterie of

artisans who denounced the alchemists, this attitude being most clearly

expressed in works such as Biringuccio's "Pirotechnia" and Agricola's

"De Re Metallica."51 The split is at the same time a response to

changing economic relationships, in particular, the collapse of the

guilds. An increasingly laissez-faire economy challenged both the

feudal notion of maintaining secrecy about a craft's techniques and

the oral tradition that had been the basis of initiation into these

"mysteries." Pressure to reveal these secrets, to make them accessible

to all by way of Gutenberg's movable type, led to the publication of

craft handbooks (like those of Biringuccio and Agricola) which provided

detailed accounts of processes and illustrations of guild practices

(see Plate 11). These works, the appearance of which would have been

viewed with horror in the Middle Ages, now served the interests of a

large and amorphous social class. Craft processes themselves had become

commodities; and secrecy, revealed knowledge, and microcosm/macrocosm

analogies were seen as superfluous and even inimical by an artisanry that

was increasingly caught up in a market economy. Thus, when the surgeon

Ambroise Paré (1510-90) was accused of having betrayed guild secrets,

he felt confident in replying that he was not of those men who "make a

cabala of art."52 Indeed, the whole notion of scientific organization

which was trumpeted by Bacon in the "New Atlantis" was completely

incompatible with the medieval ideal of deliberate secretiveness.

Plate 11. Separating gold from silver, from De Re Metallica (1556).

Courtesy, The Bancroft Library, Unversity of California, Berkeley.

the idea of an inner psychic landscape (in our terms), or original

participation, was partly lost, technology was able to judge the

alchemical tradition from the point of view of technical clarity and

precision and, of course, find it sorely lacking. As we have seen, the

language of alchemy is dreamlike, symbolic, imagistic, but this world

of resemblance was disintegrating. Carrots were not bottles, lions no

longer devoured the sun, androgynes were inventions in the same category

as unicorns. Cryptic phrases such as "the sun and his shadow complete

the work" did not glaze pots or extract tin, and names for substances

such as "butter of antimony" or "flowers of arsenic" (which, however,

lasted down to the late eighteenth century) were now seen as cumbersome

and inefficient. The whole alchemical imagery of things being themselves

and their opposites, or possessing inherent ambiguity, was now regarded

as stupid, incomprehensible, an obstacle to be rooted out. Biringuccio,

Bacon, Agricola, Lazarus Ercker, and many others deliberately set

themselves against the tradition of wonder at nature, of credulity

about fabulous beasts and plants and stones -- a tradition that had

characterized medieval literature from Pliny to Agrippa. The notion of

'satsang' still present in esoteric disciplines like Zen and yoga,

that the truth is miraculously communicable through a relationship

with a teacher, was an anathema to these men, who correctly saw that

the attempted domination of nature depended on cognitive clarity. The

collapse of an ecological, or holistic, orientation toward nature went

hand in hand with the rejection of dialectical reason.53

Other books

Katrina, The Beginning by Elizabeth Loraine

Fire And Ash by Nia Davenport

Hitting the Right Notes by Elisa Jackson

A Little Folly by Jude Morgan

The Secret Life of Houdini by William Kalush, Larry Sloman

Falling in Love With Her Husband by Ruth Ann Nordin

Orpheus by DeWitt, Dan

Burning Desire by Donna Grant

Baseball Pals by Matt Christopher