Read The Real History of the End of the World Online

Authors: Sharan Newman

The Real History of the End of the World (17 page)

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

7.7Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Â

Â

A

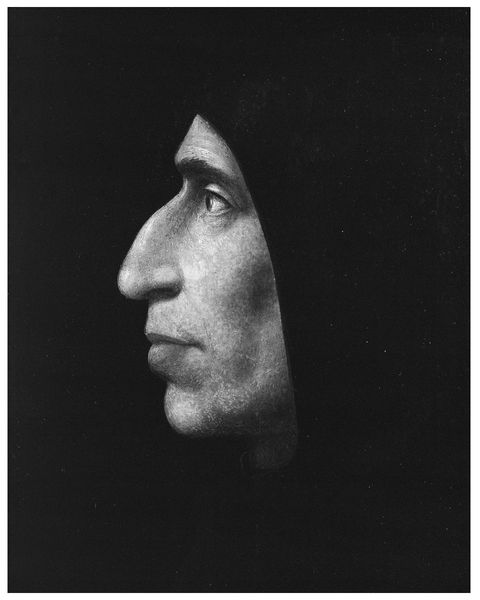

t the height of the Renaissance, the city of Florence was home to some of the finest artists in the world. Under the rule of Lorenzo de Medici, known as Lorenzo the Magnificent, Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Verrochio, and Michelangelo lived and worked in Florence. It was also, at the end of the fifteenth century, a city rife with corruption and rapidly facing bankruptcy. Into this contradiction walked a Dominican monk with a gift for preaching. His name was Giralamo Savonarola. If the portraits of him are near to accuracy, he was tall and thin with penetrating eyes and a nose one could hang umbrellas on.

t the height of the Renaissance, the city of Florence was home to some of the finest artists in the world. Under the rule of Lorenzo de Medici, known as Lorenzo the Magnificent, Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Verrochio, and Michelangelo lived and worked in Florence. It was also, at the end of the fifteenth century, a city rife with corruption and rapidly facing bankruptcy. Into this contradiction walked a Dominican monk with a gift for preaching. His name was Giralamo Savonarola. If the portraits of him are near to accuracy, he was tall and thin with penetrating eyes and a nose one could hang umbrellas on.

Born in the town of Ferrara in 1452, Savonarola seems to have been concerned about sin and the end of the world from his youth. In 1472, even before he became a monk, he wrote a poem in which he lamented that the world was upside down, Rome had abandoned its moral leadership, and the end was coming.

2

Of course, at twenty, many people feel this way, but Giralamo didn't grow out of his gloom.

2

Of course, at twenty, many people feel this way, but Giralamo didn't grow out of his gloom.

Savonarola.

Erich Lessing / Art Resource, New York

Erich Lessing / Art Resource, New York

After becoming a monk, he was sent to Florence from 1482 to 1486 before going on to San Gimignao, where he began his apocalyptic preaching career. One of his earliest sermons had for its subject: “Do penance, for the Kingdom of God is at hand.”

3

3

In 1490, Lorenzo di Medici called Savonarola back to Florence and installed him as abbot of the Medici monastery of San Marco. As abbot, Savonarola encouraged the monks to create works of sculpture, paintings, and architecture. He even hired Sienese nuns to illuminate manuscripts.

4

Despite his insistence on penance and austerity before the arrival of the Apocalypse, Savonarola had an appreciation for the importance of art that fit in with the times.

4

Despite his insistence on penance and austerity before the arrival of the Apocalypse, Savonarola had an appreciation for the importance of art that fit in with the times.

His preaching over the next few years continued to dwell on the need for penance. He may have coined the phrase

bonfire of the vanities,

when, in February 1497, he convinced many Florentines to burn their wigs and other finery in an orgy of renunciation. His visions of the end were modeled on those of Joachim of Fiore but added to from visions of his own, which he was understandably reluctant to tell his followers about, at least at first.

bonfire of the vanities,

when, in February 1497, he convinced many Florentines to burn their wigs and other finery in an orgy of renunciation. His visions of the end were modeled on those of Joachim of Fiore but added to from visions of his own, which he was understandably reluctant to tell his followers about, at least at first.

When the French king Charles VIII invaded Italy in 1494, many in France and Italy hoped that he was actually the reincarnation of his distant ancestor Charlemagne, making his promised return as the New World emperor.

5

Savonarola at first believed that Charles was more of an Antichrist, or at least his helper, on his way to punish sinful Florentines. He changed his mind when Charles withdrew from Florence. “The Florentines began to see themselves and their city as divinely chosen to be a new elect to lead the world to salvation.”

6

5

Savonarola at first believed that Charles was more of an Antichrist, or at least his helper, on his way to punish sinful Florentines. He changed his mind when Charles withdrew from Florence. “The Florentines began to see themselves and their city as divinely chosen to be a new elect to lead the world to salvation.”

6

This view was helped considerably by Savonarola. During the crisis of the French invasion, Lorenzo's son, Piero de Medici, had panicked and given King Charles two Florentine towns. He and his brothers then fled the city, and when they tried to return, they were blocked by angry citizens. At the same time, Savonarola was part of a city delegation to Charles and he managed to convince the king that the French and the Florentines should be allies. When he returned to Florence, he became the de facto leader of the city. All of his sermons of coming disaster were fresh in the minds of the Florentines. They recognized Savonarola as a prophet as well as a diplomat. In the ensuing weeks, Savonarola moved from believing in an imminent apocalypse. Instead he began to think that the New Jerusalem could be established in Florence with the Millennium to follow.

Savonarola told the Florentines that they were a chosen city, something they already may have believed. In a sermon from December 1494, he preached, “God has everywhere prepared a great scourge, nevertheless, on the other hand, he loves you, . . . Mercy and Justice have come together in the city of Florence.”

7

7

A republic was established in Florence, something Savonarola had not preached or expected but which he welcomed.

8

Like the later Fifth Monarchists, he thought that there should be no king but Christ. In a more earthly vein, he suggested that they form a government on the Venetian pattern, with checks and balances and a rotating leadership.

9

8

Like the later Fifth Monarchists, he thought that there should be no king but Christ. In a more earthly vein, he suggested that they form a government on the Venetian pattern, with checks and balances and a rotating leadership.

9

Savonarola's visions became more spectacular, as is seen in the

Compendium of Revelations,

which he wrote to defend himself from the accusations of heresy that had reached Pope Alexander. The work is in the form of a dream vision, a prophetic literary form of great antiquity. In this dream, after several debates with the Tempter, in which he explains his own actions and that of Florence, Savonarola arrives in heaven. There he ascends through the nine choirs of angels to the throne of the Virgin Mary and announces that he is “the legate of the Florentines to the throne of the Queen of Heaven.” He begs her to ask God to grant the people of Florence just rulers and the ability to live according to the Divine Laws. Jesus then approaches and gives Savonarola a ruby that symbolizes his Passion, “So that mercy and grace might be given to the people of Florence.”

10

Compendium of Revelations,

which he wrote to defend himself from the accusations of heresy that had reached Pope Alexander. The work is in the form of a dream vision, a prophetic literary form of great antiquity. In this dream, after several debates with the Tempter, in which he explains his own actions and that of Florence, Savonarola arrives in heaven. There he ascends through the nine choirs of angels to the throne of the Virgin Mary and announces that he is “the legate of the Florentines to the throne of the Queen of Heaven.” He begs her to ask God to grant the people of Florence just rulers and the ability to live according to the Divine Laws. Jesus then approaches and gives Savonarola a ruby that symbolizes his Passion, “So that mercy and grace might be given to the people of Florence.”

10

With that sort of patronage, it would be hard for anyone to contradict Savonarola.

In one area, however, the prophetic reformer went too far for even the radical Florentines. In a sermon made at the height of his influence, on March 18, 1496, Savonarola suggested that women be allowed to decide reforms that they would be affected by. Within a few days, he was convinced to make a retraction and nothing more was heard of the plan.

11

11

He cautioned the people of Florence that the Fifth Age, of the Antichrist and conversion, was beginning. He predicted the conversion of the Turks within the next few years. He also hoped for the Joachite coming of the Angelic Pope who would renew the corrupt Church of Rome. Now, Pope Alexander VI was, among many other things, the father of Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia. While I think that many of the stories about his orgies at the Vatican and incest with Lucrezia are probably greatly exaggerated, Alexander certainly used the papacy as a private fief, handing out property to his family and having his enemies mysteriously vanish. Savonarola, who had supported Alexander's strongest adversary, the French king, and had preached against the excesses of Rome, soon arrived at the top of the papal hit list.

The cynic and admirer of Cesare Borgia, Machiavelli, wrote that he thought Savonarola a charlatan. Of course, Machiavelli was a friend of the now-exiled Medici family.

12

But he had a number of other problems with the reformer. Some had to do with Savonarola's ideas of the running of a Christian state in Florence and the fact that Machiavelli had lost a seat on the city council to a supporter of Savonarola. Another matter that offended Machiavelli was Savonarola's determination to wipe out homosexual behavior. While not gay himself, Machiavelli saw nothing wrong with being so and felt that Savonarola was intruding into people's private lives.

13

It is not surprising that Savonarola was homophobic; toleration in any form was not part of his Christian city. He also called for the expulsion of prostitutes and Jews from Florence.

14

12

But he had a number of other problems with the reformer. Some had to do with Savonarola's ideas of the running of a Christian state in Florence and the fact that Machiavelli had lost a seat on the city council to a supporter of Savonarola. Another matter that offended Machiavelli was Savonarola's determination to wipe out homosexual behavior. While not gay himself, Machiavelli saw nothing wrong with being so and felt that Savonarola was intruding into people's private lives.

13

It is not surprising that Savonarola was homophobic; toleration in any form was not part of his Christian city. He also called for the expulsion of prostitutes and Jews from Florence.

14

Savonarola had his defenders, too, among them the writer Pico della Mirandola. The first printing press had appeared in Italy ten years before and was put to good use in what became a war of pamphlets between supporters of the pope and those of Savonarola.

But the issue boiled down to one inescapable fact. Pope Alexander had ordered Savonarola to come to Rome and answer his accusers. The preacher decided that this would not be a good career move. Instead, he had sent the pope a pamphlet. Because Savonarola was a Dominican friar, his disobedience was grounds for excommunication. Added to this was his “preaching of false doctrine.” This was enough of an excuse for Alexander. On May 13, 1497, the pope declared Savonarola no longer among the community of Christians.

15

15

This put the citizens of Florence into a serious quandary. They could either rally around Savonarola and risk being condemned with him or they could turn their backs on their prophet. Some in Florence were already disillusioned and glad of a reason to back out, but many of his devoted followers continued to protest his innocence with another round of pamphleteering. It was pointed out in these that Alexander had bought the office of pope, something widely known but politely not mentioned. This opened another can of worms, the longstanding debate about whether sinful clerics could perform valid sacraments.

16

16

In February 1498 Savonarola defied the papal ban on preaching. After several weeks of tension, it was decided that he would undergo the ordeal by fire on April 7, 1498, to prove the righteousness of his teaching. He apparently forgot the appointment. His nonappearance was seen as an admission of guilt and the next day the Monastery of San Marco was raided by supporters of the pope. Savonarola and two of his staunchest followers were arrested, tried and, on May 23, hanged and their bodies burned. Worried that his followers would claim the ashes as relics, the authorities had the remains thrown into the Arno River.

17

17

Perhaps the Florentines would have protected Savonarola longer if he had been less strict and kept the brothels open. It was said that they reopened shortly after his execution and hymns of praise were heard coming from grateful patrons as they entered the houses.

18

18

But the impact Savonarola had on Florence and on the increasingly vocal dissidents in Europe could not be washed away as easily as his remains. If hymns were sung in derision, many more were hummed quietly in remembrance of the man who was now a martyr.

The Republic of Florence lasted another twenty years before the Medicis returned. If it wasn't a New Jerusalem, it at least had learned that princes weren't absolutely necessary to government.

One of the most long-lasting repercussions of the debate over Savonarola was the realization of the power of the press. Savonarola was especially canny in his use of the medium. His pamphlets, written in Latin, traveled all over Europe. They were embellished with woodcuts of the prophet preaching, chatting with nuns, and bringing down the Apocalypse on unbelievers. They were reprinted long after his ashes had floated out to sea and many still exist, as do printed copies of his sermons. The next century would see the blossoming of the seed planted in Florence by Savonarola and many more attempts to create a City of God on earth.

One of the most intriguing aftereffects of the life of Savonarola is that, despite his fight with the pope, some Catholics considered him a martyr, too. Even the saints Catarina de' Ricci and Philip Neri “revered him as a martyr and master of the contemplative life.”

19

There is even today a group lobbying for his canonization.

20

19

There is even today a group lobbying for his canonization.

20

In looking at later groups that tried to create a New Jerusalem, it might be worth remembering the example of Savonarola and Florence. His preaching began by assuming that the end of the world would be any day. His attitude changed with his success; he began to hope that the world could change rather than be destroyed. He learned the hard way that Florence wasn't ready for perfection. The unanswerable question is what would have happened if all of Florence had stood with him? Would they have fought to the death or come to a compromise that would have allowed them to live as they liked? Would they have committed mass suicide, like some other religious groups, despite the fact that it was a mortal sin?

There is a subtle tipping point in a movement after which there is no turning back. The Florentines tipped toward their old lives. Many other followers of the prophets chronicled in this book went the other way.

2

Donald Weinstein, “Savonarola, Florence and the Millenarian Tradition,”

Church History

27, no. 4 (1958): 293.

Donald Weinstein, “Savonarola, Florence and the Millenarian Tradition,”

Church History

27, no. 4 (1958): 293.

3

Loc. cit.

Loc. cit.

4

A. Hayett Mayor, “Renaissance Pamphleteers, Savonarola and Luther,”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin

new ser. 6, no. 2 (1947): 67.

A. Hayett Mayor, “Renaissance Pamphleteers, Savonarola and Luther,”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin

new ser. 6, no. 2 (1947): 67.

5

This prophecy had been invented for Charles VI a hundred years before, but since it didn't come true, there was no point in wasting it, and the prophecy was recast for Charles VIII. See McGinn, 187.

This prophecy had been invented for Charles VI a hundred years before, but since it didn't come true, there was no point in wasting it, and the prophecy was recast for Charles VIII. See McGinn, 187.

6

Jack Fruchtman Jr. “The Apocalyptic Politics of Richard Price and Joseph Priestly: A Study in Late Eighteenth-Century English Republican Millennialism,”

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

new ser. 73, no. 4 (1983): 10.

Jack Fruchtman Jr. “The Apocalyptic Politics of Richard Price and Joseph Priestly: A Study in Late Eighteenth-Century English Republican Millennialism,”

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

new ser. 73, no. 4 (1983): 10.

7

Quoted in Rob Hatfield, “Botticelli's Mystical Nativity, Savonarola and the Millennium,”

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes

58 (1995): 83.

Quoted in Rob Hatfield, “Botticelli's Mystical Nativity, Savonarola and the Millennium,”

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes

58 (1995): 83.

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

7.7Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Any Other Name: A Longmire Mystery by Craig Johnson

Hemlock Veils by Davenport, Jennie

The Spirit Banner by Alex Archer

Listen! by Frances Itani

Recipe for Love (Entangled Select Suspense) by Dyann Love Barr

The Godlost Land by Curtis, Greg

Cameron and the Girls by Edward Averett

Seaweed Under Water by Stanley Evans

Tachyon Web by Christopher Pike

Chimaera by Ian Irvine