Read The Real History of the End of the World Online

Authors: Sharan Newman

The Real History of the End of the World (12 page)

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

11.91Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

By the way,

Myrddin

is also Welsh for the number “one thousand.”

fd

I'm sure that the people who try to predict the future with computers will be delighted with the one and zeroes. More predictions may soon follow.

Myrddin

is also Welsh for the number “one thousand.”

fd

I'm sure that the people who try to predict the future with computers will be delighted with the one and zeroes. More predictions may soon follow.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Setting the Clock

The Maya

Â

Who will be the prophet? Who will be the priestwho shall interpret truly the word of the book?

Â

Â

Â

Â

E

xplanations of the Maya, their Long Calendar, and the end of the world in 2012 have been covered extensively in the media in the past few years. I will address that fateful date in its own section. It seemed though that it might be a good idea to find out more about the Mayans before trying to understand how or if they arrived at 2012 as an end date and what it means. I have noticed that very few of the television talking heads who tell viewers that the Maya have prophesied the end of our world actually know how to read Mayan glyphs or have degrees in archaeoastronomy. That doesn't make them wrong, just rather suspect in my mind. So I have read books and articles by people who are scholars of Mayan culture, both ancient and modern, as well as scientists who are intrigued by the intricacy of the calendars and astronomical computations.

ff

xplanations of the Maya, their Long Calendar, and the end of the world in 2012 have been covered extensively in the media in the past few years. I will address that fateful date in its own section. It seemed though that it might be a good idea to find out more about the Mayans before trying to understand how or if they arrived at 2012 as an end date and what it means. I have noticed that very few of the television talking heads who tell viewers that the Maya have prophesied the end of our world actually know how to read Mayan glyphs or have degrees in archaeoastronomy. That doesn't make them wrong, just rather suspect in my mind. So I have read books and articles by people who are scholars of Mayan culture, both ancient and modern, as well as scientists who are intrigued by the intricacy of the calendars and astronomical computations.

ff

It's true that the Mayan calendar is very complex. For one thing, the Maya based their counting system on fingers and toes, instead of just fingers. So the base is twenty instead of ten. Spanish colonizers noted that in trading with them in cacao beans, the Maya counted, “by fives up to twenty, and by twenties up to one hundred and by hundreds up to four hundred, and by four hundreds up to eight thousand. . . . They have other very long counts and they extend them in infinitum.”

fg

And this is cacao merchants multiplying in their heads! Imagine what the priests who spent all their time studying the sky could come up with.

fg

And this is cacao merchants multiplying in their heads! Imagine what the priests who spent all their time studying the sky could come up with.

They also devised their calendar as most early people did, according to the seasons and the stars, trying to gauge the optimum times for planting, harvesting, and other essential occupations. But the Mesoamericans went far beyond that or any known method of dating. The reason they did this is still debated. Therefore, let's begin by looking at the Maya themselves, where they came from and what may have happened to the civilization that built the stone cities of Mesoamerica.

The Maya didn't spring from nowhere. Their predecessors were the Olmec, who may have developed the mother language, both written and oral, for the four Mayan language groups. The language of the Olmec has not yet been satisfactorily deciphered, although it's thought to be in the Zoquan language group.

fh

Their writing system was adapted by the Maya, although the meaning and pronunciations of the glyphs may not be identical.

fh

Their writing system was adapted by the Maya, although the meaning and pronunciations of the glyphs may not be identical.

The Olmec also may have designed the first 260-day “short” calendar and, perhaps, also the Long Count Calendar.

fi

Their civilization dates from around 1200 B.C.E., although that didn't appear spontaneously, either. There is pottery evidence of a developing culture that goes back another seven thousand years.

fj

Recent excavations by paleobotanists indicate that people along the Gulf of Mexico were raising corn and sunflowers as early as 5000 B.C.E., although it's not known if they were the same as the people who became the Olmec.

fk

fi

Their civilization dates from around 1200 B.C.E., although that didn't appear spontaneously, either. There is pottery evidence of a developing culture that goes back another seven thousand years.

fj

Recent excavations by paleobotanists indicate that people along the Gulf of Mexico were raising corn and sunflowers as early as 5000 B.C.E., although it's not known if they were the same as the people who became the Olmec.

fk

The Olmec are probably also responsible for the base twenty number system and the invention of the zero.

fl

The Maya seem to have built considerably on their work.

fl

The Maya seem to have built considerably on their work.

As in many other cultures, the Maya saw time as cyclical, rather than linear. Things happened in patterns, not in exactly the same way each time, but within knowable possibilities.

fm

In the

Chilam Balam

, one of the few Mayan books that survive (although written in Roman letters), this cycle is shown as a wheel. Within it are the

katunob

, “an endlessly recurring sequence of thirteen twenty-year periods, . . . each with its designation and characteristic events.”

fn

This is known as the Short Count Calendar. In it, a year contains 260 days. Of course, the Maya knew that the solar year is 365+ days. So there is another calendar called the

Haab,

or “vague year,” of eighteen months with twenty days each, along with five “unlucky days” at the end.

fo

These two calendars were used at the same time. Each day in the Short Calendar had an equivalent day in the

Haab

but, because the cycles were of different lengths, 3

Pop

could be 3

Kimi

in one year and 7

Ak'bal

in another. It takes fifty-two years for the correlations to start repeating. The first day of the year, 0

Pop

, was originally set at the winter solstice. However, because neither calendar was exact, it happened that 0

Pop

fell on the winter solstice only every 1,507 years. This, plus archaeological evidence, has led scholars to think that this calendar was in use by 550 B.C.E.

fp

fm

In the

Chilam Balam

, one of the few Mayan books that survive (although written in Roman letters), this cycle is shown as a wheel. Within it are the

katunob

, “an endlessly recurring sequence of thirteen twenty-year periods, . . . each with its designation and characteristic events.”

fn

This is known as the Short Count Calendar. In it, a year contains 260 days. Of course, the Maya knew that the solar year is 365+ days. So there is another calendar called the

Haab,

or “vague year,” of eighteen months with twenty days each, along with five “unlucky days” at the end.

fo

These two calendars were used at the same time. Each day in the Short Calendar had an equivalent day in the

Haab

but, because the cycles were of different lengths, 3

Pop

could be 3

Kimi

in one year and 7

Ak'bal

in another. It takes fifty-two years for the correlations to start repeating. The first day of the year, 0

Pop

, was originally set at the winter solstice. However, because neither calendar was exact, it happened that 0

Pop

fell on the winter solstice only every 1,507 years. This, plus archaeological evidence, has led scholars to think that this calendar was in use by 550 B.C.E.

fp

But that's only the Short Count years. For the Long Count, the Maya used another year, this time of 360 days, called a

tun;

twenty

tuns

made a

ka'tun

and twenty

ka'tuns

was a

bak'tun,

or 144,000 days.

fq

The Long Count seems to have been computed starting at August 11 or 13, 3114 B.C.E. “a date on which astronomers have found no momentous celestial event to have occurred.”

fr

tun;

twenty

tuns

made a

ka'tun

and twenty

ka'tuns

was a

bak'tun,

or 144,000 days.

fq

The Long Count seems to have been computed starting at August 11 or 13, 3114 B.C.E. “a date on which astronomers have found no momentous celestial event to have occurred.”

fr

Thirteen

bak'tuns

was the cycle that has created all the stir. According to post-conquest sources, the last creation ended in a great flood.

fs

The next cycle does indeed end in December 2012. At that point, the calendar will “flip” to 13.0.0.0.0. Whether this is like a car odometer hitting a hundred thousand miles or something more momentous remains to be seen.

bak'tuns

was the cycle that has created all the stir. According to post-conquest sources, the last creation ended in a great flood.

fs

The next cycle does indeed end in December 2012. At that point, the calendar will “flip” to 13.0.0.0.0. Whether this is like a car odometer hitting a hundred thousand miles or something more momentous remains to be seen.

What did the Maya use these calendars for? It looks as if they were mainly religious in nature. The principal information on the Maya culture comes from the four books that remain from before the Spanish conquest; the observations of the conquerors, particularly Bishop Diego de Landa; and the many inscriptions on Mayan artifacts. We may have a very skewed impression of the Maya from this. As Michael Coe says, “[It's] as though all that posterity know of ourselves were to be based upon three prayer books and

Pilgrim's Progress

.”

ft

If someday the Great Mayan Novel turns up and there's nothing in it about the gods, then all scholarship on their culture will have to be reconsidered.

Pilgrim's Progress

.”

ft

If someday the Great Mayan Novel turns up and there's nothing in it about the gods, then all scholarship on their culture will have to be reconsidered.

However, at least one section of Classical Maya society (400- 900 C.E.) seems to have been vitally concerned with the relationship between man and the universe. How far it reached from the priests and the ruling class to the military, artisans, farmers, and others is hard to tell. But the fact that the general population tolerated, or even encouraged, the public practice of very bloody sacrifices and rites indicates that most of them were also believers.

What the Maya believed is not completely clear, either. I think they viewed the world very differently from most of us today, and so even if the tangle of gods, dates, movements of the stars and ritual were figured out, we could still not really enter into the understanding the Maya had of their place in the cosmos. Of course, that shouldn't stop anyone from trying. However, those who insist that they know exactly what the Maya believed probably haven't studied them enough.

For one thing, the Maya were not one monolithic culture. There were several cities, each with its own variation on central myths. Some of these incorporated the local ruling families into the creation stories. Others had gods, or aspects of the same gods, which were venerated only by that city. There were also gods who appeared in different forms: old, young, infant, animal, or natural force.

fu

In the

Popol Voh

, one of the pre-conquest books written in Maya (but in Spanish characters), the story of the creation as known to the Quiche Maya is told.

fu

In the

Popol Voh

, one of the pre-conquest books written in Maya (but in Spanish characters), the story of the creation as known to the Quiche Maya is told.

In it, the Plumed Serpent of the sea and the Heart of Sky, with the help of other gods, created the earth, plants, and animals. The gods wanted some acknowledgment for the cleverness of their creation, but the animals only squawked or hooted or roared. So they fashioned puppet people from wood and clay, but these went about living without paying attention to the gods. Therefore the gods sent the flood to destroy them all. (In the Mayan story there are no righteous survivors.) Just to be certain, “Gouger of Faces: he gouged out their eyeballs. . . . Sudden Bloodletter: he snapped off their heads. . . . Crunching Jaguar: he ate their flesh. . . . Tearing Jaguar: he tore them open. They were pounded down to the bones and tendons, smashed and pulverized even to the bones.”

fv

fv

Added to this, their domestic animals attacked the puppet people; their pots and pans burned them; trees threw them off their branches, and caves closed before them when they tried to hide.

fw

Soon, there was only a small remnant of them left, which became the monkeys.

fw

Soon, there was only a small remnant of them left, which became the monkeys.

This is what happens to a people who don't respect the hard work their gods went through to create them.

The creation of the current human race and the history and genealogy of the Quiche Maya make up the rest of the

Popol Vuh.

In the story, there is constant interaction between the people and the gods. Often the lords of the land take on the aspects of gods, changing shape, like Plumed Serpent, who could become an eagle or a jaguar or “nothing but a pool of blood.”

fx

Popol Vuh.

In the story, there is constant interaction between the people and the gods. Often the lords of the land take on the aspects of gods, changing shape, like Plumed Serpent, who could become an eagle or a jaguar or “nothing but a pool of blood.”

fx

Blood was essential in most of the Mayan rites. Timing seems to have been as well. The correct sacrifice must be performed according to the season and the stars. Their calculations for the movements of Venus and Mars were particularly complicated. The Maya had charts to predict solar and lunar eclipses. The

Dresden Codex

, a book written in Mayan glyphs, contains many of these charts and calculations. Although they have been provisionally translated, the book is rather like having a manual for a machine one has never seen. The people who used it knew what it meant, but modern scholars can only guess, using inscriptions on monuments and pottery as well as remembered traditions of modern-day Maya. It does appear that they believed that gods sent messages through the sky. Missing one could result in disaster.

fy

Therefore the Maya had dozens of ways to observe the movements in the heavens, to measure the ecliptic and the distance of planets and stars relative to it.

fz

Dresden Codex

, a book written in Mayan glyphs, contains many of these charts and calculations. Although they have been provisionally translated, the book is rather like having a manual for a machine one has never seen. The people who used it knew what it meant, but modern scholars can only guess, using inscriptions on monuments and pottery as well as remembered traditions of modern-day Maya. It does appear that they believed that gods sent messages through the sky. Missing one could result in disaster.

fy

Therefore the Maya had dozens of ways to observe the movements in the heavens, to measure the ecliptic and the distance of planets and stars relative to it.

fz

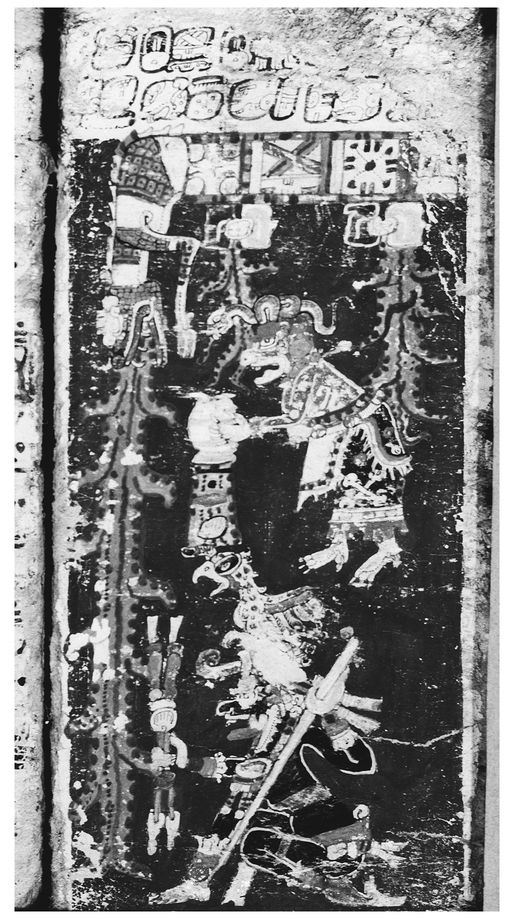

A Mayan representation of the destruction of the world, from the

Dresden Codex. Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesietz /Art resource, New York

Dresden Codex. Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesietz /Art resource, New York

The need for sacrifices, particularly of blood, was deemed necessary for the continued health of the society: rain, crops, animals to hunt, and so forth. The Maya fed the gods with blood in order to be fed themselves.

ga

They sacrificed captives and slaves in ways that allowed blood to flow down gutters in the altars, soaking the ground. But the Mayan priests and rulers also practiced painful rites on themselves in which men pierced their penises and women their tongues. Then they drew thorny ropes through the wounds to extract blood. The blood was mixed with incense and paper and either burned or rubbed on the stone images of the gods.

gb

ga

They sacrificed captives and slaves in ways that allowed blood to flow down gutters in the altars, soaking the ground. But the Mayan priests and rulers also practiced painful rites on themselves in which men pierced their penises and women their tongues. Then they drew thorny ropes through the wounds to extract blood. The blood was mixed with incense and paper and either burned or rubbed on the stone images of the gods.

gb

The pattern of the sacrifices and other rites used only the 260-day calendar, and apparently by the end of the Classical period, the Long Count Calendar was no longer part of the calculations, although it continued to be used for other things.

It seems that the Maya, like the Egyptians, were more concerned with keeping this world going than with when it was going to end. “They had a crucial role to play in the cyclical drama, through their calendrical computations, their related rituals, and even their wars and revolts. Theirs was the task of helping the gods to carry the burden of the days, the years and the

katuns

and thereby to keep time and the cosmos in orderly motion.”

gc

katuns

and thereby to keep time and the cosmos in orderly motion.”

gc

Only one ancient Mayan artifact has been found with a prediction by the Palequue Maya that says anything about the end of the current

bak'tun,

and that was found on an, unfortunately, broken inscribed stone. It says that “the 13th

Pik /Bak'tun

will end and . . . a god or gods called

Bolon Yokte'

will descend.”

gd

The unbroken section of the stone doesn't say who this god is or what he/she/they/it is going to do when he/she/they/it arrive. The Palenque Maya seem to have believed that we are not living in the last creation and that after 13.0.0.0.0 will come 14.0.0.0.1 and not the end of the world.

ge

bak'tun,

and that was found on an, unfortunately, broken inscribed stone. It says that “the 13th

Pik /Bak'tun

will end and . . . a god or gods called

Bolon Yokte'

will descend.”

gd

The unbroken section of the stone doesn't say who this god is or what he/she/they/it is going to do when he/she/they/it arrive. The Palenque Maya seem to have believed that we are not living in the last creation and that after 13.0.0.0.0 will come 14.0.0.0.1 and not the end of the world.

ge

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

11.91Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Behind Palace Doors by Jules Bennett

Unbridled by Beth Williamson

Doubting Our Hearts by Rachel E. Cagle

Spartan Frost by Estep, Jennifer

The Problem at Two Tithes (An Angela Marchmont Mystery Book 7) by Clara Benson

Cowboy For Hire by Duncan, Alice

Family Secrets by Kasey Millstead

2 The Dante Connection by Estelle Ryan

Better Off Red by Rebekah Weatherspoon

The High-Life by Jean-Pierre Martinet