The Rape of Europa (5 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Stunned by this speech, the audience entered the portals of the new museum, already dubbed “Palazzo Kitschi” and “Munich Art Terminal,” to a stultifying display carefully limited to idealized German peasant families, commercial art nudes, and heroic war scenes, including not a few works by jurist Ziegler himself. The newly disciplined art press dutifully reported that “sketchiness had been rigorously eliminated” and that “only those paintings had been accepted that are fully executed examples of their kind, and that give us no cause to ask what the artist might have meant to convey.” Despite the fact that the Führer was portrayed “as a mounted knight clad in silver armor and carrying a fluttering flag” and “the female nude is strongly represented … which emanates delight in the healthy human body,” the show was essentially a flop and attendance was low.

40

Sales were even worse and Hitler ended up buying most of the works for the government.

Quite the reverse was true of the exhibition of “Degenerate Art,” which opened on the third day of this Passion of German Art. Ziegler, who must

have been quite exhausted by now, again began the proceedings with a speech echoing Hitler’s words of the previous day, adding a condemnation of museum directors who had expected their countrymen to look at such “examples of decadence.”

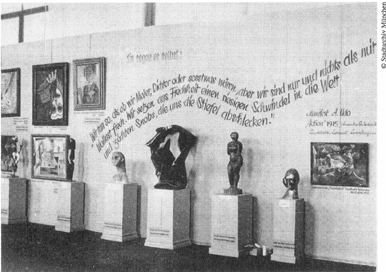

“Degenerate Art” show: typical installation showing “Anarchist-Bolshevist” wall (Inscription: “‘They say it themselves: We act as if we were painters, poets or whatever, but what we are is simply and ecstatically impudent. In our impudence we take the world for a ride and train snobs to lick our boots.’ Manifesto A. Udo, Aktion, 1915. Anarchist-Bolshevist: Lunarscharski, Liebknecht, Luxembourg.”)

In a run-down building formerly used to store plaster casts were jammed the hundreds of works removed from the museums in the previous weeks. Over the door of one gallery were inscribed the words “They had four years.” One hundred thirteen artists who had not understood the message were represented. Schlemmer and Kirchner illustrated “barbarous methods of representation.” The antimilitary works of Dix and Grosz were called “art as a tool of Marxist propaganda against military service.” Expressionist sculpture was accused of promoting “the systematic eradication of every last trace of racial consciousness” for its depiction of blacks. Another room was “a representative selection from the endless supply of Jewish trash that no words can adequately describe.” Abstract and Constructivist pictures by Metzinger, Baumeister, and

Schwitters were simply called “total madness.” The catalogue, a badly printed and confused booklet, was laced with the most vicious quotes from Hitler’s art speeches. The walls were covered with mocking graffiti. To “protect” them, children were not allowed in.

Before it closed on November 30 more than 2 million people poured through this exhibition, which was often so crowded that the doors had to be temporarily closed. Reactions were mixed. An association of German officers wrote to the Chamber of Art to protest the inclusion of the works of Franz Marc, who had been killed at Verdun and awarded the Iron Cross. Marc’s

Tower of Blue Horses

was quickly withdrawn, but four other pictures by his hand remained. Although the Hannoverian collector Dr. Bernhard Sprengel was inspired to rush out and buy Nolde watercolors from a Munich gallery, and many art lovers came to see their favorites for the last time, both Hentzen and Rave sadly note that the propaganda had had its effect: the government had successfully exploited the desire of all Germans to forget the grim harshness of the recent past, and the reality of a world in economic and social turmoil. This their modern painters would not let them do. The new reality would be fashioned by the Nazi regime alone.

A few weeks after these momentous ceremonies, “total purification” began in earnest. Curators continued their delaying tactics, often aided by continuing aesthetic confusion on the part of the purgers:

In Berlin the commission at first confiscated anything even a little impressionistic…. When Ziegler came the next morning and moderated the guidelines, a large number of pictures were put back. Herr Hofmann found everything Degenerate … especially the landscapes of Slevogt and Corinth…. The

Inntal Landscape

(1910) by Corinth was … according to Hofmann a typical case of how, in one picture, genius and decadence could be combined…. The landscape brilliant—the sky decadent!

41

Fortunately for this picture, the landscape prevailed, and it hangs in Berlin to this day. (Corinth, whose early works were widely acclaimed as “very German,” posed a problem that was neatly resolved by barring only the works he painted after 1911, the year in which he had suffered a stroke.)

All over Germany curators presented excuses in their desire to preserve their collections: pictures were in the photography studio or being restored. Corinth’s

Trojan Horse

was saved when Rave suggested that the Nationalgalerie quickly trade it for a less “degenerate” work still owned by the artist’s widow. Some officials refused any removal order not in writing. In Berlin’s Print Room the purification committee was presented with

Stacks of boxes containing more than 2,000 prints. After pulling out 588, they left, confused and exhausted. That night curator Willy Kurth managed to replace some of his most valuable prints with lesser ones by the same artists from another museum, and thus to preserve many priceless works by Munch, Kirchner, and Picasso.

42

Not all museums were so scrupulous: officials in Hamburg turned over some of their forbidden pictures, including a Degas, to eager dealers. But all these subterfuges saved only a tiny fraction of the collections. In the end, the confiscation committees removed nearly 16,000 works of art from German public collections.

There now arose the problem of what to do with this mass of art. The “Degenerate” show, touring Germany after its Munich opening, only took care of a few hundred works. For the time being the purged objects were taken to Berlin and stored in a warehouse in the Copernicusstrasse. The Bavarian Museums carefully insured their shipment before it left, declaring “substantial market value,” and the Chamber of Culture generously paid the premium.

43

Goering, who had been forming his own collection for some time, was the first to recognize the potential monetary value of this trove. He sent his agent, Sepp Angerer, to put aside paintings which would have value abroad, a foray which netted him pictures by Cézanne, Munch, Marc—and no fewer than four van Goghs. These he used to obtain cash for the Old Masters and tapestries he preferred. Angerer sold Cézanne’s

Stone Bridge

and two of the van Goghs,

Daubigny’s Garden

and the

Portrait of Dr. Gachet

, to the banker Franz Koenigs in Amsterdam for about RM 500,00?.

44

Goering, always scrupulous about appearances, paid the Nationalgalerie RM 165,000 for its purged work, a bargain since, according to Rave,

Daubigny’s Garden

alone was worth more than RM 250,000.

Hungry for foreign currency, other Nazi leaders also secretly cashed in on this bonanza, but their dealings were only a drop in the bucket. In March 1938 Franz Hofmann, chairman of the confiscation committee, declared the museums to be “purified.” The fate of the remaining works awaited the Führer’s orders. Hitler had seen the deposits for himself in January. In June he signed a law freeing the government from all claims for compensation for the “safeguarded” works, one of the first official uses of the euphemism which was to become an international watchword in the next decade. His action opened the way to unrestrained commerce. Goebbels was pleased and wrote in his diary that he hoped to “make some money from this garbage.”

45

A Commission for the Exploitation of Degenerate Art was formed. On it sat the chief of Alfred Rosenberg’s art operations,

Robert Scholz; Ziegler; photographer Heinrich Hoffmann; and, in an arrangement that makes modern insider-dealing scandals seem childish, Berlin art dealer Karl Haberstock, who had begun his career at the Paul Cassirer firm and had ties to all the major European dealers. To avoid any appearance of impropriety the commission members were supposed to refrain from selling. Four well-known dealers were appointed to take over the actual marketing of this extraordinary inventory: Karl Buchholz, Ferdinand Möller, Bernhard Boehmer, and Hildebrand Gurlitt. All were men who had handled modern art for years. Möller had represented Nolde and Feininger; Boehmer was a friend of Barlach’s. Gurlitt had been fired from Zwichau for exhibiting modern artists, and Buchholz was the mentor of Curt Valentin, who had named his New York gallery in Buchholz’s honor and who would be present at the Lucerne auction.

The international market had already been well primed for these sales, as such farsighted museum directors as Count Baudissin had begun deaccessioning “unacceptable” works soon after Hitler’s advent to power.

46

The dealers were instructed to sell for foreign currency without “arousing positive evaluations” at home. Fortunately, the operation was managed by an enlightened lawyer and amateur art historian, Rolf Hetsch, who knew the true value of the contents of the warehouse. He set up a salesroom in Schloss Niederschonhausen, just outside Berlin. The four dealers could buy things for very little as long as they paid in foreign currency. Even Germans could buy if they had dollars, sterling, Swiss francs, or objects of interest to the Führer.

47

A painter of modest means, Emanuel Fohn, who lived in Rome, heard of the sales in late 1938. Remembering Ziegler from student days at the Munich Academy, he rushed to consult him and was given Hetsch’s name. Hetsch agreed to accept works from Fohn’s collection of nineteenth-century German paintings in exchange for “degenerate” ones. Fohn took them back to Italy and promised to return these paintings someday to Germany. At his death the collection was indeed left to the Städtische Museum in Munich, the birthplace of his wife, Sofie.

48

Word of the trade soon went much farther afield. The director of the Basel Kunstmuseum, Georg Schmidt, persuaded his city fathers to give him SFr 50,000 to invest, declaring that it was their duty to save good art. He spent it well both at the Schloss and at the Lucerne auction. Curt Valentin, still a German citizen, was able to obtain from this source much of the inventory which established him as a major New York dealer, and continued to make frequent and risky trips to Berlin. Hetsch sold works for practically nothing, simply to get them out of the country. A postwar study lists more than twenty pages of objects distributed from the Nation-algalerie’s collections alone. Even a little sample of the prices paid makes unbelievable reading:

| M. Beckmann | Southern Coast | $20 to Buchholz |

| M. Beckmann | Portrait | SFr 1 to Gurlitt |

| W. Gilles | 5 Watercolors | $.20 each to Boehmer |

| W. Kandinsky | Ruhe | $100 to Möller [now Guggenheim Museum, New York] |

| E. Kirchner | Strassenzene | $160 to Buchholz [now MoMA, New York] |

| P. Klee | Das Vokaltuch der Sängerin Rosa Silber | $300 to Buchholz |

| Lehmbruck | Kneeling Woman | $10 to Buchholz 49 |

Needless to say, the anointed dealers often did rather better on the resales, which they did not always report to the Commission.

In the fall of 1938 Exploitation Commission member and dealer Karl Haberstock suggested to Hitler and Goebbels that a public auction would increase these minimal revenues. He brought a Swiss crony and fellow Cassirer alumnus, Theodore Fischer, to look over the depositories. Together they chose the 126 works which would be sold in Lucerne on that sunny day the following June. It was none too soon. Despite all the trading activity, the Copernicusstrasse warehouse remained distressingly full. Franz Hofmann, fanatically desirous of carrying out Hitler’s purification policies to the letter, pushed to get rid of the remaining works, which he declared “unexploitable.” He suggested that they be “burned in a bonfire as a symbolic propaganda action” and offered to “deliver a suitably caustic funeral oration.”

50

Shocked at the idea of such destruction, Hetsch and the dealers took away as much as they could. But Goebbels agreed to Hofmann’s plan, and on March 20, 1939, 1,004 paintings and sculptures and 3,825 drawings, watercolors, and graphics were burned as a practice exercise in the courtyard of the Berlin Fire Department’s headquarters just down the street. The works in Schloss Niederschonhausen were reprieved and gradually sold or traded away. The whole process of “purifying” the German art world, and its “final solution” in flames, eerily foreshadows the terrible events to come in the next six years.

Other books

The Treasure OfThe Sierra Madre by B. Traven

The Last Kingdom by Bernard Cornwell

Give Me You by Caisey Quinn

Telling Lies to Alice by Laura Wilson

The Weird Tales of Conan the Barbarian by Robert E. Howard

The Nemesis Program (Ben Hope) by Scott Mariani

The End of the Line by Stephen Legault

In Her Day by Rita Mae Brown

The Anchor Book of Chinese Poetry by Tony Barnstone

Mission: Tomorrow - eARC by Bryan Thomas Schmidt