The Rape of Europa (36 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

On June 22 Leningrad had lain shimmering in the strange light of the White Nights. All who write of these events are struck that the attack took place on this beautiful and festive night when Leningraders traditionally celebrate the arrival of summer. News of the invasion did not arrive at the

Hermitage until noon on June 23, an hour after the vast museum had opened. As the word passed, the galleries quickly emptied. Curators were called in, and the grim processes of evacuation were set in motion.

Although the surprise had been complete, the Russian museums had, like all others in Europe, long since ranked their objects and prepared packing materials. But evacuating the Hermitage, vast showcase of the Czarist collections, would be an incredible task at the best of times. Its holdings, some 2.5 million objects, ran the gamut: paintings, delicate porcelains, glass, coins, jewelry, massive antiquities, furniture, and every other decorative art. In the first hours director Iosif Orbeli, who had fought for years to keep the collections intact, ordered the forty most valuable items rushed to the basements. The first air raid came twenty-four hours after the notice of war. Curators patrolled the roofs ready to quench fires while their fellow citizens mobilized to build trenches and fortifications around the city.

In the constant daylight, packing went on around the clock. Art students came in to help. Paintings separated by tissue paper were rolled twenty to sixty on one cylinder, covered with oilcloth, and packed in long coffinlike crates. Works which had to be left in their frames, such as panel paintings, were crated in bunches according to size. Only one picture, Rembrandt’s enormous

Return of the Prodigal Son

, got its own box. Other crates held Coptic textiles, Scythian and Hellenistic gold, eighteenth-century jewelry, snuffboxes, and even medieval German beer mugs. Specialists from the Lomonosov porcelain factory packed thousands of dishes and ornaments. To minimize shock, delicate Greek vases were painstakingly filled with crumbled cork before being wrapped. The days were hot, and work went on next to windows opened wide. The sounds of doves cooing were punctuated by the roar of aircraft over the city. As the crates were filled and sealed, relays of Red Navy sailors moved them to the entrances or basements. Soon the galleries were piled with empty frames—a sight now so familiar in the Western museums.

The first train of twenty-two boxcars containing some half a million items left on July 1. Antiaircraft guns were attached at each end. Director Orbeli, tall, bearded, and imposing, wept as it moved out. Before each station the staff halted the train and deployed guards. Miraculously unharmed, it arrived five days later in the Siberian town of Sverdlovsk, where the objects were democratically distributed among a former Catholic church, the Museum of Atheism, and the local art museum.

Back in Leningrad the packing went on. A second shipment left on July 20 with seven hundred thousand objects. These gigantic transports represented less than half of the museum’s holdings and preparations for a third

continued, but by August their packing materials were nearly gone. Fifty tons of shavings, three tons of cotton wool, and almost ten miles of oilcloth had been consumed. Far worse was the news that German forces had begun to move again and had cut the rail link to the East. On September 4 artillery shells began to fall within the city. The German front line was only eight and a half miles from the museum. Now everything that could be taken away went down to the basements, while upstairs, the immovable, giant malachite urns, enormous marble tabletops, and magnificent panelling, floors, and mosaics of the palace itself awaited their fate.

6

Packing chandeliers at the Hermitage

It was just as well that the exhausted citizens of Leningrad were not privy to Hitler’s thoughts about their city. In the evenings at the Wolf’s Lair the Nazi chief held forth endlessly to his staff on his view of history and his plans for Russia, monologues that were recorded at Bormann’s order. Hitler explained that Germany had missed out on the distribution of “Lebensraum” in the past because of its involvement in religious war. The founding of St. Petersburg, he mused, had been a catastrophe for Europe. It must therefore “disappear completely from the earth, as should Moscow.” Only then, he theorized, would the Slavs “retire to Siberia,” and provide Germans their needed space. The Führer was not worried about

the works of art in these cities. He assumed, correctly, that they had either been taken out to the east by train or stored in castles in the countryside.

7

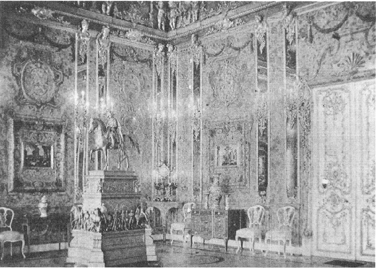

The scenes in these “castles” had been equally frantic as those in the Hermitage. One of the first rooms to be emptied at the palace of Catherine the Great in the town of Pushkin, formerly known as Tsarskoye Selo, was the famous Amber Room, so called because it was not only entirely panelled with delicately carved sheets of amber, but contained chairs, tables, and ornaments made of the same material. The latter were easily packed, but the panels proved too difficult to remove and were left in place.

The palaces had far less packing material than the Hermitage. To save precious paper and shavings, some things were even packed in freshly mown hay; at the Palace of Pavlovsk the carefully preserved uniforms of Czar Nicholas II and his wife’s dresses were used as padding. At 5 a.m. on July 1 the first Pavlovsk shipment of thirty-four crates left for Gorky, accompanied by chief curator Anatoly Kuchumov. Work continued night and day, even as the artillery barrages began and the male work force, called to arms, diminished.

One cannot rush this sort of packing. Delicate and complex objects such as chandeliers, clocks, and furniture had to be dismantled before being wrapped. Careful records of where each separate piece had been packed were necessary. When a whole set of furniture could not be taken, a sample was chosen and sent. Some things were simply too big. At Pavlovsk the fine collection of Greek and Roman statues was dragged and pushed on carpets and planks by stalwart lady packers down into a remote corner of the cellars and walled up so cleverly that they were never discovered by the Germans. The same women managed to bury without trace most of the statuary in the park, including a fourteen-foot-high work by Triscorni depicting the Three Graces.

By August 20 three more shipments had left the palaces, which by now were filling up with refugees fleeing before the armies. Soon afterward, curator Anna Zelenova of Pavlovsk, who had directed the last operations, found that she was cut off from Leningrad. On August 31 the palace was taken over as a Red Army headquarters. Despite all, packing continued in the hope that trucks could somehow be sent from Leningrad to take the crates to safety. On September 16 Zelenova was told that Pavlovsk was within German-held territory, and that their patrols were already in the famous white birch groves of the park. She and a colleague fled on foot through the battle zone, taking the vital inventories and storage maps with them. As they made their way through the fields they could see the Chinese Theater at the neighboring Catherine Palace burning. Five harrowing

hours later they arrived in Leningrad on an Army truck filled with wounded. It would not be a comfortable refuge. At Pavlovsk alone some eight thousand objects remained and now awaited the arrival of the Germans.

8

A prewar photograph of the Amber Room in the Catherine Palace. The whereabouts of the panels remains a mystery.

The invaders were prepared. Von Kunsberg’s Second Special Battalion immediately moved into the newly conquered area. There were certain Germanic things that had been targeted for them, for the Kümmel Report which had listed such items in the West also had a Russian section. One of von Kunsberg’s first objectives was the Amber Room, which had originally adorned the Prussian palace of Mon Bijou, and which, legend has it, was given to Peter the Great by the Soldier-King Frederick William II in exchange for a battalion of large Russian mercenaries. Von Kunsberg’s well-equipped minions made short work of removing the Amber Room panels, which, dismantled and carefully packed in twenty-nine crates, were sent off to the museum at Königsberg, showplace for the top gatherings from the Eastern Territories. The museum lost no time in unpacking and installing its new acquisition. The

Frankfurter Zeitung

announced to the home front in a front-page article on January 3, 1942, that the unique

assemblage, “saved by German soldiers from the destroyed palace of Catherine the Great is now on exhibition.” Next was the famous Gottorp Globe, a miniature planetarium in which twelve people could sit and contemplate the arrangement of the heavens depicted on the inside. The globe, made for the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp in the seventeenth century, was greatly admired by his descendant, Czar Peter III, and eventually presented to him. Now, the Nazi press reported, “through our soldiers’ struggle this unique work of art has been obtained and will again be brought back to its old home at Gottorp.”

9

The Special Commandos did not limit themselves to these German creations. They and the rest of the Army, indeed not behaving in a “knightly fashion,” took anything they could pry loose from the myriad palaces and pavilions around Leningrad, right down to the parquet floors. They opened packed crates and helped themselves to the contents. Mirrors were smashed or machine-gunned, brocades and silks ripped from the walls. At Peterhof, just outside Leningrad, the machinery controlling the famous cascading fountains was destroyed, and the gilded bronze statues of Neptune and Samson upon which the waters played were hauled off to the smelting furnace in full view of the distraught townspeople.

The depredations around Leningrad were just the beginning. All across the newly conquered lands those in the know went after the “Germanic” things they had long coveted. Sometimes the Germanic attribution took a bit of doing. The ubiquitous SS operative Kraut, who had worked so hard in Poland, wrote on July 18 to SS headquarters that he hoped it would be possible to “bring home” the magnificent, eleven-foot-high bronze doors of the ancient cathedral of Novgorod. These were thought to have been made originally by a Magdeburg artist in the twelfth century for the Polish cathedral of Plock, which Kraut argued was now “a town belonging to the German Reich.” The doors, after a complicated history, had arrived in Novgorod in 1187. He also warned his colleagues not to be fooled by the fact that in Novgorod the portals were referred to as the Korsun Gate, “which gives the impression that they are an ancient Greek work originating from the Crimea, thus camouflaging their German origin.” Kraut was disappointed to find later that the doors had been “dragged off” by the Russians.

10

This was fortunate, as the Nazis would soon ravage the cathedral and all the city’s museums.

In the Baltic states, a German commission that had been negotiating for months for cultural items which it claimed belonged to ethnic Germans “resettled” in the Reich and in Poland after Stalin took over, now was able to “safeguard” the disputed items and ship them off to Danzig.

11

And Admiral Lorey of the Zeughaus, Berlin’s military museum, was once again

informed that the Führer wished him to undertake the recovery of German weaponry lost in wars back to the Middle Ages, expense being no object.

12

Other books

Just a Little Surprise by Tracie Puckett

Only Emma by Sally Warner, Jamie Harper

Pestilence (Jack Randall #2) by Wood, Randall

Fire Bringer by David Clement-Davies

Inverted World by Christopher Priest

His Captivating Confidante (Secret Sentinels) by Lisa Weaver

Sparks & Cabin Fever by Susan K. Droney

After Ever by Jillian Eaton

Daughter of Silk by Linda Lee Chaikin

The Rottenest Angel by R.L. Stine