The Rape of Europa (17 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Louvain Library, 1940

In Paris, life was affected only slightly. It was noticed that diamonds, easily portable, were selling well. Fancy ladies involved in war work, including the Duchess of Windsor, still lunched with one another, now dressed in the snappy uniforms of the Red Cross and other such organizations. Concerts, exhibitions, and horse races went on. During the rare airraid alerts, the chic concierges served coffee and soup in their shelters, though few could compete with that of the Ritz, which is said to have been furnished with Hermès sleeping bags.

10

Art dealers were open, but trade was slow, and stocks of contemporary works diminished as younger artists were drafted along with everyone

else. From the journal

Beaux Arts

, which had a column devoted to the whereabouts of artists, curators, and dealers, it could be learned that the brothers Durand-Ruel, Pierre and Charles, were serving as pilot and interpreter, respectively, that Bonnard was in Cannes, and Louvre curator Gerald van der Kemp was in a telegraph unit.

An amazing number of artists, anxious to sell, still remained in Paris. This worked greatly to the advantage of any collector who was on the scene, and especially of the American Peggy Guggenheim, who had come to Paris determined to “buy a picture a day” for her projected modern gallery. Indeed, the artists flocked to her, some desperate to accumulate enough money to leave France. “People even brought me paintings in the morning to bed, before I rose,” she reported.

11

In no time she had works by Tanguy, Pevsner, Dali, Giacometti, Man Ray, and Léger. So optimistic was she that, even as the Germans invaded Norway on April 9, she rented a large apartment in the place Vendôme in which to hang her new acquisitions, and began to remodel it. After May 10 her circle rapidly diminished, but Peggy stayed until the last, buying Brancusi’s famous

Bird in Space

on June 3 as German planes bombed the suburbs. Brancusi, who hated to sell anything, wept as she took it away.

12

In all the apparent normalcy of the

drôle de guerre

, the empty, echoing galleries of Paris’ great museums had been a sobering reminder of what might come. The French museum people had not slackened their efforts to perfect the protection of their treasures. After the major works had reached Chambord they had begun to redistribute the collections among eleven other châteaux to the west of Paris, all within a convenient radius around Chambord, and as far from the advertised battle zone around the Maginot line as possible. Six of the eleven were located north of the Loire. In November the

Mona Lisa

, resting on an ambulance stretcher in a sealed van escorted by two other vehicles, was transferred to Louvigny, near Le Mans. The curator who stayed by her side for the trip emerged semiconscious from the van and had to be revived, but Leonardo’s inscrutable lady was fine. With her went Fra Bartolommeo’s

Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine

and other principal works of the Italian school. The Rubens of the Medici gallery went to the Château of Sourches, where they were later guarded by the curator Germain Bazin. Courtalain, near Châteaudun, received the Egyptian collection. Just south of the Loire thirty truckloads went from Chambord to Brissac, near Angers, where they were joined by the Apocalypse tapestries from that city. Cheverny sheltered works from the Cluny Museum, and the great Talleyrand domain at Valençay took in the major sculptures: the

Venus de Milo, Winged Victory

, and Michelangelo’s

Slaves

, as well as the crown jewels.

13

At Chambord itself, curators had unpacked needed archives and generally tried to make themselves at home in the huge château, unoccupied for centuries, in which the plumbing was as historic as anything else. Life at this repository was somewhat more relaxed for the art professionals than it was at the châteaux still occupied by their owners, where the country life continued full tilt. At Cheverny there was an active hunt with its pack of hounds whipped in by huntsmen in red and gold. Valençay’s ducal owner had a magnificent if noisy collection of parrots in cages scattered about the premises. The curators, regarding adaptation to these new experiences as part of their professional duty, soon learned that “thirty or forty technical words well placed in conversation were enough to make us worthy conversationalists, and cure us of any inferiority complexes.”

14

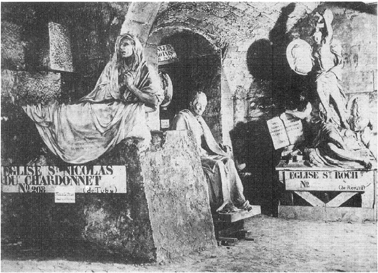

All through the winter more was brought out from Paris in whatever transportation could be begged or borrowed by Musées director Jacques Jaujard from donors, employees, and friends. Other convoys took the contents of the museums of the Ville de Paris, separately administered, to additional châteaux in the same region. In Paris proper the cellars of the Pantheon and Saint-Sulpice gradually filled with sculpture and stained glass from nearby churches and such institutions as the Comédie-Française. One curator was highly amused to find Houdon’s statue of arch anticleric Voltaire surrounded by saints and angels pointing heavenward.

15

Similar scenes took place all over France. In Bayeux, just in case, the mayor ordered the famous tapestry rolled, sealed in its special lead box, and stored in a concrete vault.

Despite all the preparations, the reality of the invasion of Holland and Belgium was a shock. Henri Matisse, caught in Paris, rushed to a travel agent and booked passage to Rio on a ship leaving Genoa on June 8. As he walked out of the agency he met Picasso by chance, and expressed his dismay at the dismal performance of the French armies. Picasso explained,

“C’est l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts,”

to him a perfect description of the Maginot mentality.

16

On June 4 a great wheeling maneuver of the main body of the German invasion forces placed them directly north of the clustered French repositories and only 160 miles away with no Maginot line in between. They advanced relentlessly. Before this juggernaut millions from Belgium, the north of France, and soon Paris, fled in a tidal wave. Exhausted, filthy people and their children, cats, and dogs jammed into cars swathed in mattresses, pushing grotesquely loaded bicycles or simply walking, streamed into the parks of Chambord and Valençay, reminding one art historian of

Callot’s

Misères de la Guerre.

Every train and station was jammed. And into this river of despair were launched, once again, the greatest treasures of France. The

Mona Lisa

was the first to depart with a few other hastily packed works from Louvigny, the northernmost depot. By June 5 she was safely in the ancient Abbey of Loc-Dieu in the Midi near Villefranche-de-Rouergue. More than three thousand pictures would join her there as a result of the extraordinary efforts of the French curators. The last convoy crossed the Loire on June 17, only hours before the bridges were blown.

Saint-Sulpice, Paris: Voltaire among the saints

South of the river, conditions on the roads were terrible. The biggest convoy inched painfully toward Valençay. One of the truck drivers, Lucie Mazauric, terrified because she had only managed to pass her driver’s test the day before, later wrote:

The hardest was the beginning, from Chambord to Valençay. Cars were going in every direction. The jammed roads slowed our progress, and I had the misfortune, driving up toward Valençay, to hook my bumper over that of Mme. Delaroche-Vernet. We would never have gotten it loose, and would have been crushed by the flood of cars being driven by dazed drivers who seemed not to see any obstacles, had a

strong youth not unhooked us…. This act of kindness helped us bear the rest, and the rest was difficult…. German aircraft constantly flew up and down the roads. If they had wanted to attack … the exodus would have been a carnage.

17

At Valençay, which was already jammed with curators and refugees, they stopped for the night and slept badly, listening to the sounds of artillery barrages, for most their first experience of this. At dawn the convoy left again in the terribly beautiful weather which had blessed this whole invasion, spending a second night in a village schoolhouse on mattresses. The next day, passing through countryside where no one seemed to be in charge, they were pleased to note that mentioning the Louvre was enough to get them the gasoline they needed. They arrived at Loc-Dieu, trucks in dire need of maintenance, on the day of the Armistice.

On June 10 the French government had also fled Paris to join its masterpieces in châteaux beyond the barrier provided by the Loire. Its departure was not unexpected. So encumbered were the roads that the ministers took more than twelve hours to drive the 160 miles to their assigned domains around Tours. Now it was their turn to discover the traditional discomforts of country life. No one had remembered the minimal telephonic equipment cherished by château dwellers to this day. The equal dearth of bathing facilities led to surprising encounters of famous personages in the halls: both Churchill and the omnipresent mistress of the French Premier, the Countess de Portes, were seen wandering about swathed in voluminous red silk dressing gowns in search of bathrooms.

18

It was not until June 13 that French Commander in Chief Weygand, with the encouragement and assistance of the neutral American and Swiss embassies, declared Paris an open city.

19

This was as much a military decision as an aesthetic one: Weygand wanted to prevent the total encirclement of the Army defending the city. Churchill disapproved; he had urged that Paris be defended, as the “house to house defense of a great city” would have “enormous absorbing power.”

20

German troops entered Paris the next day. Retreating again, the government, as helpless as the 8 million other refugees, moved on to Bordeaux.

Thousands of privately owned works of art were also on the move in the chaotic invasion days. The French museum administration had taken in a large number of private holdings, including many works belonging to the major Jewish collectors and dealers. At Moyre and Sourches were items belonging to the Wildensteins, various Rothschilds, M. David David-Weill

(chairman of the Conseil des Musées), and Alphonse Kann. Brissac sheltered more. But these collections, which represented only a fraction of the privately held works in Paris, were not among those which were transported south by the Musées. The rest were dealt with in all sorts of ways. Peggy Guggenheim, who had been refused space in the Louvre sanctuaries because, she later claimed, “the Louvre decided the pictures were too modern and not worth saving,” frantically began removing her pictures from their stretchers on June 5. They were packed in three large crates which she managed to send to Vichy, where they were hidden in a friend’s barn.

21

Before fleeing to New York via Lisbon, the dealer Paul Rosenberg left 162 major works in a bank in Libourne, just outside Bordeaux. This deposit contained no less than 5 Degas, 5 Monets, 7 Bonnards, 21 Matisses, 14 Braques, 33 Picassos, plus a good selection of items by Corot, Ingres, van Gogh, Cézanne, Renoir, and Gauguin. One hundred more Rosenberg pictures went to a rented château at nearby Floirac.

22

Matisse, who had been staying with Rosenberg in Bordeaux, was so horrified by the maelstrom of refugees fighting to board anything that would take them away that he changed his mind about leaving France. It took him two months, moving slowly from town to town across the south of France, to reach his favorite Hotel Regina in Nice. Once there, he wrote to his son in New York that “it seemed to me I would be deserting. If everyone who has any values leaves France, what remains?”

23

Georges Braque too was on the road, with his wife, studio assistant, and as many paintings as he could fit in his car. When he arrived in Bordeaux, Braque used the same bank as Rosenberg, entrusting to it part of his modern collection and, unfortunately as it would turn out, one Cranach portrait.

Other books

Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree by Tariq Ali

Hometown Girl by Robin Kaye

Hemp Bound by Doug Fine

Submit (Songs of Submission) by CD Reiss

L8r, G8r by Lauren Myracle

Destiny's Rift (Broken Well Trilogy) by Sam Bowring

Mausoleum by Justin Scott

The White Dragon by Salvador Mercer

Romeo's Ex by Lisa Fiedler

DowntoBusiness by Dena Garson