The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (9 page)

11

The Ideal Warrior

The Benjamite story about the 700 left-handed slingmen demonstrates that left-handedness was a serious problem in warfare even thousands of years ago. Why else would anyone take the trouble to gather so many left-handed people together and organize them into a military unit of their own? The problem still exists today, in fact it has barely changed.

Organized military action demands a great deal of the soldier, and left-handedness is undesirable. No matter how inconspicuously left-handers tend to function in normal circumstances, in battle they suddenly become a real danger to their comrades. A group of hooligans can turn itself into an army only through discipline, by doing exactly the same thing on command, like a machine. This kind of dis cipline gives it so much power and effectiveness that it can defeat poorly organized opponents, even those that are theoretically far stronger. The ancient Greeks knew this, with their phalanxes of lancers who did little else but dourly persist in walking side by side with their long lances thrust out ahead of them. That orderly block of men, bristling with iron spikes, simply steamrollered across everything that stood in its way. Using roughly the same approach, but with short swords sticking through their tightly linked walls of rectangular shields like the flails of a gigantic threshing machine, Roman legions hacked their bloody path through half the known world. When serious trouble erupts, these tactics are still used today by units of riot police all over the world, except that they wield batons rather than the deadly Roman

gladius

. On all essential points the approach is the same, with serried ranks of anonymous men steered as a single unit like automatons. Military combat worked this way right up until the First World War, when the machine gun put an end to a military tradition that was almost 3,000 years old.

Up to that point, the left-handed soldier presented a serious problem. Effective armies depended on two things: discipline, which ensured that when push came to shove soldiers would not run away, and uniformity. left-handedness violated that uniformity.

Before the invention of gunpowder, a disciplined unit of infantry depended on the relatively effective protection of an unbroken line of shields. Imagine a left-handed soldier coming to stand among them, holding his shield in his right hand. Not only would the left-hander create a dangerous gap in the unit’s cover, he would seriously obstruct the man to his right. That’s not all. A right-handed soldier moves to the left as he steps forward, so that he can strike from behind his shield, but in that position left-handed soldiers are at their most vulnerable. They will instinctively move in the other direction, causing chaos among the men. On commands such as ‘right turn’ and ‘left turn’ a soldier’s equipment can all too easily get tangled up with another’s. In short, with an obdurate left-hander in the ranks, who needs enemies?

Even today the military world continually runs up against this problem. The bolt of a rifle is on the wrong side for left-handers, so it takes them longer to reload. All standard rifles eject empty shells to the right, away from a right-handed shooter. A left-hander holds the gun to the left shoulder and so runs the risk of hot cartridge cases flying at his or her face, or right arm, which supports the barrel. Some modern firearms, though not all, are designed in such a way as to avoid this problem, but even so the left-handed soldier is at a disadvantage because the butt is shaped to fit the right shoulder. The left shoulder against which he or she braces a rifle therefore has to put up with more punishment than strictly necessary. left-handed models are not the solution. When called upon to do so, soldiers have to be able to use the gun carried by the soldier next to them. There’s no time to work out how best to handle an adapted rifle; you must grab it and use it without having to think. So even in the most modern of wars, uniformity, consistency and predictability are essential to any successful fighting unit. A left-handed soldier does not fit in.

There are some circumstances in which a left-handed soldier may be useful. As a right-hander you can shoot around the end of a wall to your left, but if the wall lies to your right you are forced to expose yourself to the enemy’s line of fire. Here left-handers are in their element. There have always been people in army circles who dreamed of an ambidextrous soldier, the ideal warrior, who could wield a sword, pike or shield with the left hand as easily as with the right, mount a horse from either side with equal ease, and shoot just as effortlessly and accurately from either shoulder.

In the final decades of the nineteenth century it seemed as if that dream was about to become a reality. It was a time of great optimism and faith in progress. On the political front Europe was relatively peaceful between 1871 and 1914, partly as a result of a complex system of treaties and alliances. True, in Russia and the Far East there were conflicts of various kinds, and from 1899 to 1902 the Boer War raged in South Africa, but that all seemed little more than a bit of bother at the world’s margins. The West was proud of its unprecedented level of civilization, not yet defiled by the two disastrous world wars of the twentieth century. Railways had opened up the possibility of long-distance overland travel and immense construction projects like the Suez Canal and the Panama Canal had proven how far man could bend nature to his will. In less than a century the steamship and the steam train had made the whole world accessible. The first cars were starting to crawl around, and in 1903 mankind took off when Wilbur and Orville Wright made their first powered flights on the beach at Kitty Hawk. There seemed to be no limit to what technology could do. The world was whatever we made of it.

At the same time impressive advances were being achieved in science: so impressive that lord Kelvin, discoverer of absolute zero and the driving force behind the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cable, was convinced that physics had virtually completed its task. ‘There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement’, he prophesied. He had no inkling, convinced as he was that ‘x-ray is a hoax’, of the discoveries that were just round the corner on the subatomic level. In retrospect the game proper had yet to begin.

Even by this point Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory was starting to have far-reaching consequences. Although his theory was misunderstood more often than not, two things had penetrated the consciousness of the general public: human beings were closely related to animals, especially apes, and people were not endowed by God with eternal and immutable characteristics but had evolved gradually over time. They could therefore change. Why should they not be malleable, at least to some extent?

Under the influence of all of this, a new kind of interest developed in the phenomenon of right- and left-handedness. If human characteristics were not set in stone, then surely it must be possible to change them at will. Our closest relatives, the apes, showed no sign of hand preference, so why would we not be capable of creating, through training, a two-handed, more complete person? The fact that apes had not developed to anything like the same extent as humans was simply ignored.

At the start of the twentieth century this attitude led to the founding of an association, the Ambidextral Culture Society, which gained a considerable following in fashionable circles. Devotees of two-handedness were convinced that one-handedness was the last serious handicap preventing us from achieving the supreme ideal of the modern, highly educated and well brought-up person, representing complete self-fulfilment. Children, as long as they were correctly trained in the equal use of their two hands, would grow into perfect people, no longer hampered by a preference either way. It remained unclear why hand preference was such a dreadful thing, aside from the fact that the human being apparently has two virtually identical hands. In this sense the Ambidextral Culture Society was a worthy forerunner of later all-embracing fads such as the fashion for anti-authoritarian childrearing that prevailed in the early 1970s, or the Bhagwan movement of the subsequent decade.

As is characteristic of movements of this sort, the ambidextrous ideal lacked a well-considered foundation. People rushed to claim prominent figures from history as its posthumous defenders. The great eighteenth-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau featured yet again among the chosen few. A myth was born. Even today, long after the ambidextrous movement faded into history, he is still regularly presented as an advocate of a two-handed upbringing.

Rousseau’s supposed predilection for ambidextrousness is based on a passage in his 1762 book

Emile

in which he writes about the development and raising of children. He says that the only habit a child should learn is the habit of not having habits. He should not be carried consistently on one arm or the other, he should be encouraged to shake either hand, and in general he should be allowed to use both hands without distinction. Poor Rousseau. He was simply voicing a protest against the conventional pressure to use the ‘correct hand’ and appealing for children to be allowed to choose for themselves, but his readers interpreted his approach as grounds for forcing children to be ambidextrous. Rousseau’s appeal for permissiveness was effortlessly translated into a demand for coercion.

The driving force behind the movement was a certain John Jackson, who in 1905 published a passionate appeal for two-handedness and a two-handed upbringing under the title

Ambidexterity

. Its fore word was written by no less prominent a figure than Lieutenant General Lord Baden-Powell, founder of the scouting movement and hero of the wars against the Ashanti in the closing years of the nineteenth century – complete with a double signature, written simultaneously with both hands.

Baden-Powell was a man with far-reaching ideas about many things. He had a strong faith in the optimal training of the human body, which for a military man was of course only sensible. On the one hand this gave rise to the scouting movement as a means of developing the average boy’s body to perfection. On the other, he was convinced that one-sidedness in people, whether it was a matter of hands, legs or eyes, was a serious obstacle to the attainment of the perfection he demanded in a soldier. As far as Baden-Powell was concerned the importance of two-handed training from an early age was almost impossible to overstate. He claimed he could keep on top of his office work only by regularly switching his writing hand and he regretted that as a child he had not practiced writing about two different subjects at once. If for that reason alone, he cannot have been much of an intellectual. Even English lords have only one head and he doesn’t explain how his could have busied itself with two subjects at a time, each independently of the other.

Baden-Powell’s beliefs about ambidextrousness left their mark in at least one scouting custom: scouts greet each other with the left hand. This habit is only tangentially connected with hand preference, incidentally. The idea occurred to the child-loving warhorse in 1896, when a defeated Ashanti chief reverentially offered him his left hand, simply because that was the way his tribe greeted the bravest of the brave.

In the end the Ambidextral Culture Society turned out to be merely a fashionable hobby. Having led nowhere, except presumably to a certain amount of childhood misery, it faded into the background when more serious matters, such as the First World War, claimed public attention. The society seems to have existed at least until the early 1980s, when in all probability it died a silent death.

12

The Polymorphism of One-sidedness

Although the silent demise of the British Ambidextral Culture Society demonstrates that two-handedness is not necessarily the route to Nirvana, and that it seems impossible to teach by any reasonable means, in one respect the movement’s followers did on the face of it have a point. Isn’t it the case that, by tradition at least, several of the greatest artists in history used both hands? Holbein, Leonardo and Michelangelo are supposed to have been ambidextrous, for instance, and the famous British painter Sir Edwin Landseer, a close friend of Queen Victoria (who was said to be ‘two-handed’ herself). The story goes that once, when the subject of ambidexterity arose at a party, Landseer called for two canvasses and two pencils and drew, simultaneously, the head of a deer with one hand and the head of a horse with the other, to the amazement of all present. Whether or not the story is true, clearly some people are capable of achieving roughly the same impressive feats with either hand. Nonetheless, the adherents of the two-handedness doctrine had committed an elementary error of reasoning. The fact that there are people who can perform great tasks with both hands is not at all the same as saying that ambidexterity in itself leads to such astonishing achievements, or to achievements of any kind. There are plenty of people with two hands that work equally well who are not capable of doing anything particularly special with either of them. They don’t become famous; instead they have to put up with being labelled ‘all fingers and thumbs’.

The most important consequence of the existence of something resembling ambidexterity is that we cannot simply divide human beings into two categories, with a group of pure right-handers on one side and a far smaller group of pure left-handers on the other. A wide range of variation lies between the two extremes. Many left-handed people are aware that there are certain tasks they perform as if they were right-handed. Sometimes they have no choice, for example when using implements designed for right-handed people such as tin openers and cork screws. In other instances their habit has arisen under duress, as in the case of left-handers who were taught to write with their right hands, or under pressure – sometimes mild, sometimes harsh – from those who brought them up, most commonly perhaps when it comes to table manners. Sometimes things simply turned out that way. less well known is the fact that the reverse is much more common. The most bizarre case I’ve come across con cerns a purely right-handed man who does just one thing consistently with his left hand: eat. The strange thing here is that table manners are one of the few patterns of behaviour that parents can do a great deal to influence. Holding a spoon with the right hand is the norm, and in many families it’s insisted upon from an early age.

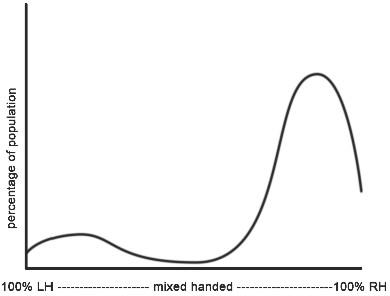

Those who don’t do everything with either their right hand or their left fall into a category of mixed-handed individuals. It’s a group that exists only in statistics, since people never refer to themselves that way in daily life. Most would say they are either right-handed or left-handed and often they are not even aware of any inconsistency in their hand preference, but if we draw a graph showing the degree to which each of a large group of individuals favours one hand or the other, it takes the form of a wave with two peaks: a low one on the left and a far higher one on the right. Most left-handers do most things with their left hand but not everything, and the same applies in reverse to right-handers. Within each of the two groups, only a minority perform all tasks with their preferred hand. Still, there are even fewer who use their two hands more or less equally. People who could be described as entirely mixed-handed seem to be exceedingly rare.

A mixed-handed person is not at all the same, incidentally, as an ambidextrous person, since he or she will use the left hand by preference or exclusively for certain tasks and the right for others. That is a quite different matter from an ability to perform any given task equally well or easily with either hand. The truly ambidextrous can do exactly that, but the question is whether such people actually exist. There are certainly those who claim to be ambidextrous, but it’s proven impossible to find people for whom it makes absolutely no difference which hand they use to write, draw, slice bread, peel potatoes, ladle soup or perform other typically one-handed tasks. If they do exist, you might almost suspect that for reasons of practicality they would unconsciously become converts to right- or left-handedness and neglect the other hand. The delights of ambidextrousness must soon pall if every time you want to note something down or put a spoon to your mouth you first have to decide which hand to use.

Of course there are plenty of people who can do certain things using either hand, with equal success and equal ease. This is in fact quite common with relatively simple tasks such as tightening a screw or whitewashing a wall. If you work so hard that your preferred hand becomes tired, you can generally switch to the other with a reasonable degree of success. The same goes for working in awkward places, but the hand used in such cases comes into play only when there’s a good reason. In normal circumstances, the favoured hand is used instinctively. When it comes to more difficult tasks, such as painting window frames or, harder still, writing and drawing, it’s almost impossible to find anyone who can easily switch from one hand to the other.

The overwhelming majority of people are either left-handed or right-handed to a significant degree, even if they do not use their preferred hand for every single task. Truly ambidextrous people are extremely rare.

Michelangelo could, apparently, which gained him a reputation for being ambidextrous. The painting of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome was not merely an artistic tour de force, it was a physical one as well. For much of the time he had to lie just under the roof, on high scaffolding. Anyone who has installed a light or mended a hole in the ceiling will have some inkling of what it means to work for long hours, day after day, with your arms raised. Gravity and lactic acid soon make the muscles weak and painful. It’s possible the world-famous painting might never have been completed if the artist had not been able to switch from one utterly exhausted arm to the other, but this does not tell us whether Michelangelo was truly ambidextrous. To find that out we would need to know whether he always started the day using the same hand and which of the two he used under normal circumstances, back in his studio. We might not be much the wiser even then, since according to contemporaries Michelangelo was a left-hander who’d been taught to paint and draw with his right hand.

Opinions are deeply divided as to the true proportions of left-handed, mixed-handed and right-handed people. This is mainly because there are almost as many ways of measuring hand preference as there are studies of the phenomenon – and fault can be found with almost all of them. The simplest method would seem to be simply to ask people which hand they favour for certain tasks, but that will render up reliable data only if we can resolve three problems faced by the questioner. Firstly, nice people – which generally includes those willing to take part in research without being offered any significant reward – like to give socially desirable answers. In other words, they try to answer in a way that fits in with their ideas about how they ought to behave, rather than according to the facts of the matter. This tends to produce conformist answers that may not be true.

The second problem appears to contradict the first. Nice people have an equally strong tendency to try to avoid disappointing the poor researcher. They’re eager to tell the questioner something interesting, and this tends to produce non-conformist rather than accurate answers. The third problem is that people sometimes have no clear idea which hand they favour for certain tasks and so, entirely in good faith, they answer incorrectly.

It seems as if everything conspires to make the number of true answers as small as possible. This has nothing to do with the subject itself; these are problems that plague all pollsters and they help to explain why political polls can be so misleading. People want both to fit in and to tell the questioner what they think he’d like to hear, and they are only partially aware of their own actions and motivations. As a result, completely unintentionally, they come up with patent untruths. If you think this cannot possibly apply to you, just consider whether at this moment you could say with certainty in which position you are usually lying when you wake up in the mornings, whether you generally cut the toe-nails of your right or left foot first and which ankle goes on top if you sit cross-legged.

A radical way of avoiding the pollsters’ problem is to ask nothing at all but to take objective measurements. One approach has been to measure the strength of the grip in each hand, with the idea that the stronger hand would be the one a person truly preferred. A man called Jules van Biervliet tried an even more subtle approach in 1897. He hung equal weights on the index fingers of both hands of his subjects and asked which was heavier. If an individual said the weight on his right finger was heavier, then he was left-handed and vice versa. Others have used all kinds of methods of measuring the size of the hands and arms, labelling the larger as the one the subject favoured.

This approach allows us to say something about people who are long dead, based on their skeletons. In 1995 researchers at the University of Southampton and English Heritage’s Ancient Monuments laboratory believed they had found evidence that the proportion of left-handed people was slightly higher in the Middle Ages than it is now. They measured the lengths of the bones in the arms of 80 peasants who were buried between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries in the graveyard at the village of Wharram Percy in Yorkshire. In 16 per cent of skeletons the left arm was longer than the right, in 3 per cent both were of equal length and in the remainder the right arm was longer. Based on the assumption that the dominant hand is more often used for carrying loads, and that the right arm would therefore become slightly longer, they concluded there were more left-handed people around in the past than now. The reason for this, they believed, was that in an illiterate world there would be less cultural pressure to be right-handed. It was a story no less muddled than it was entertaining, since cultural pressure has never been about carrying loads but instead relates to things like writing and table manners.

A huge number of carelessly designed studies of this kind have been carried out over the years, all involving the assumption that the preferred hand is the one with which we perform best in certain circumstances: exert the most force, perform the quickest moves, carry the heaviest weights or detect the most subtle distinctions. But whatever they did, the researchers came up with different figures every time, and no wonder, since power and speed are not what hand preference is all about. A few top tennis players aside, our favoured hand or arm is not noticeably stronger than the other, and the cause of hand preference does not lie in the hand or arm anyhow but in the brain, an organ that until recently divulged virtually none of its secrets.

It is therefore more helpful to record behaviour than to look at physical characteristics. After all, the way we behave is the externally visible result of how our brains work. Even this approach is not without its problems, since social and cultural pressure mean that to some extent naturally occurring left-handedness is repressed, as we see even in the tolerant Western world of today when a child learns to write. In a busily scribbling school class there are even now slightly fewer left-handers on show than are present in reality.

This creates a need to look at criteria that are independent of culture, at tasks that are performed with the preferred hand but not governed by etiquette. Back in the 1930s, American Ira S. Wile came up with a truly original solution. He calculated the percentage of left-handers based, among other things, on people he counted as they passed a busy street corner carrying an umbrella or a shopping bag. If they were using their left hands, he categorized them as left-handed. Otherwise he ticked the box for right-handedness. The idea is not entirely absurd, but in practice it was undermined by Wile’s inability to control the circumstances under which he took his measurements. A person may carry an umbrella in his left hand because he’s left-handed, or it may equally well be because his right arm is tired or aching, because he’s injured his right hand, or for a thousand other reasons that Wile could not possibly know about. No wonder he arrived at one of the highest scores of all time: almost a third of the people in Wile’s research were left-handed according to his criteria.

If the results are to be valid it’s essential to exclude the possibility that people will display a particular behaviour for reasons other than those assumed by the researcher. This explains why psychological experiments usually take place in bare, utterly boring rooms and subjects are asked to carry out minor, often apparently pointless tasks. The fewer external influences at play the better.