The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (5 page)

Superstitions about deceitfulness, such as those ways of swearing a false oath and the use of the

hecktaler

, have nothing do to with the complex of sickness and heath. They relate to a quite different theme: inversion. It’s a subject that must be almost as old as mankind and it flows directly from our tendency to polarize and to split things in two. In the Judeo-Christian world it is also directly connected with the distinction between good and evil, since here we encounter the inverse of God: the Devil. God looks like man, so he’s naturally right-handed as most of us are, but the Devil is left-handed, a reversal reminiscent of the way he demands to be kissed not on the cheek or the mouth but on the buttocks or anus.

Adam and Eve eat fruit from the tree of knowledge and are expelled from paradise. Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel, Rome.

Inversion as a characteristic of the Devil is alive and well to this day, and not just in the inverted symbols and rituals of the black mass. As recently as 2008 the Dutch Christian fundamentalist Minister for Youth and the Family, André Rouvoet, publicly declared himself proud of the fact that as a teenager he’d investigated whether pop and rock records contained messages from the Devil by playing them backwards. If he found one that did, he would break the guilty record in two – quite an effort in the days of vinyl. He insists he would do the same today.

The theme of inversion can be found the world over, but it’s by no means always a matter of good and evil. In the ancient world, sacrifices of fish or small animals to the ancient earth gods were often made using the left hand, with the creature’s head downwards. Here inversion is merely a logical consequence of the notion that the gods of heaven live above us and the earth gods beneath.

Among the Toraja on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, inversion is closely connected with the distinction between life and death. The right hand is for normal life and the living. The Toraja therefore care for the graves of their ancestors exclusively with their left hands, and even a handful of rice sacrificed to the dead must be scattered with the left. They imagine the dead as white, whereas their own skin is dark. left-handedness is unacceptable in their culture, not because the left hand is bad but simply because, shockingly, a left-hander treats other people as if they belonged to the realm of death. Offering someone a drink with the left hand strikes the Toraja as like offering someone a wreath as a birthday gift.

The left and right halves of our bodies, then, are clearly and fairly consistently connected with two themes in folklore. One is the magic of sickness and health, which resides on the left. The other is the motif of inversion. But when superstitions concern things outside ourselves and how they move around, then at first sight they make no sense. Arbitrariness reigns, we might think. In Central Europe sheep crossing from right to left are a sign of misfortune, whereas both the Romans and the native Americans thought that crows heralded death and destruction if you watched them pass from left to right. The French agree that crows are a bad omen, but they remain convinced that if the birds approach from the left then their evil effects can be avoided, so only crows coming from the right are worth worrying about. A cuckoo calling off to your left means bad luck, but to your right it’s a sign of good luck. In some places people believe that sheep or pigs bring good fortune as long as they pass on the left side. If they pass by to the right you need to watch out. In other places people are just as convinced that the opposite applies.

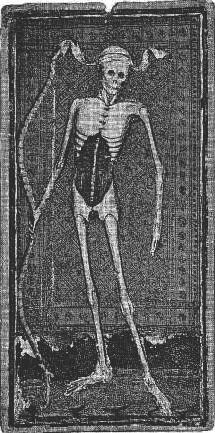

| The Tarot deck’s Death carries his bow in his right hand since – and this is surely no coincidence – he is left-handed. |  |

Official church rituals are no less muddled. Catholics make the sign of the cross by touching first the left shoulder, then the right, but Anglicans and the Eastern Orthodox do it the other way around – although with the right hand; no difference there. This probably has something to do with the fact that both groups of dissenters from the mother church wanted to differentiate themselves as far as possible from their former brothers in the faith. This is a prime example of inversion. The strangest case of inconsistency in direction concerns the ancient Romans, fervent believers in all kinds of omens that had to do with the flight of birds and natural events of that sort. The left was originally regarded as lucky, but under the influence of Greek culture the Romans seamlessly adopted the belief that the right was the favourable side. Fate, it seems, could take its cue from fashion.

The cause of all this confusion might perhaps be the absence of any natural criterion of the kind that the axis of our bodies represents in relation to our body parts. left is almost always associated with negative things because of the inversion motif, but what does left mean in the world around us? That depends whether you concentrate on where something is coming from or where it’s going to. In the former case, animals we hear to our left, that pass us to the left or cross our path from left to right may be bad omens. But if we look at their direction of movement, everything is reversed and suddenly whatever comes from the right is bad.

With circular motion too, the various beliefs look chaotic at first, but appearances can be deceptive. Here a third theme lies waiting to be discovered.

A wide range of ritual movements are performed clockwise. The processions held by Catholics always move around a church clockwise, just as a priest performing Mass moves clockwise around the altar. When new houses are blessed in today’s Europe, people process around them clockwise. In party games we take turns in clockwise rotation and cards are always dealt out that way round.

Clockwise motion can be seen as rightward in direction, so it might seem as if the connection between the right and favourableness is responsible here once again, but in the early twentieth century French sociologist Robert Hertz came up with a different explanation. He claimed that circular rituals were intended to reinforce a common bond, a sense of ‘them and us’. People turn their right shoulders towards the safe centre of the group and their left shoulders towards the hostile outside world. As a result, they automatically circle clockwise. Neither explanation can be right. Hertz does not make clear, for example, why we would choose to turn our right shoulders inwards. Surely a right-handed majority would want to use their right hands to defend themselves against a hostile outside world. Furthermore, neither Hertz’s hypothesis of cosiness nor the connection between clockwise rotation and goodness and good fortune explains why a number of traditional rituals involve anticlockwise motion.

The sports world offers one highly visible example. Almost all racetracks, whether for dogs, horses, people or cars, are used anticlockwise. The propellers of planes and helicopters turn anticlockwise too, as do windmills.

The best explanation for these phenomena presented so far lies in the path described by the sun. In the northern hemisphere the sun moves clockwise across the sky. Although they may be completely unaware of it, priests and believers who circle churches, altars or houses are following ancient heathen sun rites. They are reflecting the course of the sun as it passes around the place at the centre of the ritual: the church, the altar or the house to be blessed. Precisely the same rituals exist in the southern hemisphere, but this can be explained by the fact that all today’s dominant cultures arose in the northern hemisphere. It would be wonderful to know whether the Incas of South America or the long-lost Bantu cultures of the Congo and southern Africa had circular rituals long before the first European explorers set sail, but they all disappeared long ago, leaving no evidence as to their directional sensitivities.

The traditions of board and card games adhere to exactly the same principle. The players represent the path of the sun, the ‘turn’ is the sun itself and the point around which the sun revolves is the centre of the board or the gaming table. Each player watches the course of the game pass on the other side of the table in the direction of the sun, from sunrise on his left to sunset on his right.

So what about windmills? They may appear to turn anticlockwise, but that’s because we tend to look at them from the wrong side. The reference point for a windmill is not the chance passer-by, looking at the mill from the front, but the miller himself. He is generally inside, behind the turning sails; from his point of view they turn in the same direction as the clock and the sun.

The crankshaft and therefore the drive shaft of an internal combustion engine, as well as aeroplane propellers, simply follow the tradition that arose centuries ago when the first windmills were built. The engine in the earliest motor vehicles quickly came to occupy the place formerly taken by the horse, in front of the driver. Seen from his perspective, engines and propellers turn clockwise. The demands of industrial production soon established an unswerving standardization that was more enduring than could ever have been created by superstition.

Racetracks, finally, differ from all other circuits in the position of their reference point, which lies outside them. The crowd in a stadium or at a racetrack does not usually sit in the centre of the arena; in fact, the centre tends to be virtually empty. Instead people look on from outside. In contrast to players of board and card games, they are not participants but literally outsiders. The action they watch most closely takes place on the nearer side of the track. If the movement observed by the crowd were to circle clockwise, then the competitors would be seen to move from right to left, passing the spectators in the opposite direction to the sun. By using the track the other way round, the usual effect is preserved; the participants pass, like the sun, from left to right.

So all circular movements conform to the same principle, following the sun. The reference point is all that differs from case to case. With processions and games it lies in the thing the circuit revolves around, with windmills it lies inside the mill, with engines in the position of the driver, and at racetracks in the eye of the beholder, outside the circuit.

*

The church engagement ceremony we know today, an extension of the marriage ceremony with the rings on the right hand, is a later innovation.

7

The True Nature of left and Right

Inversion, the path of the sun and healing magic: these are the three contexts in which the left side and the left hand occur in modern-day symbolism. Only the last of the three is interesting in its own right. With inversion, the choice of the left hand is simply derived from the fact that right-handedness is the norm, and rituals inspired by the path of the sun across the sky are dictated by the fact that the sun happens to travel from left to right as seen from the dominant northern hemisphere. The left is of essential importance only in magic. The symbolic link between the left side of the body, the left hand in particular, and health and sickness, life and death, is not derived from anything else, at least not directly. It has to do purely with the opposition between left and right. This is a puzzle, since although left and right are opposites, it’s less clear what the opposite of health and sickness could be, or of life and death.

Of course with matters of this sort it’s impossible to prove anything beyond doubt. We are dealing with soft values – irrational feelings, intuitive judgements, things that lend themselves poorly to analysis – and we cannot ask our ancestors to tell us about their motives. We can’t even directly observe the foundations on which we construct our everyday, subconscious view of the world, but we can formulate a reasonable conclusion about what we suspect is going on with all that health magic and its link to the left side of the body. First we need to return to classical antiquity.

More than 2,000 years ago, in the Hellenic period, a goddess with Egyptian origins called Isis developed into a divinity that was popular all the way from England to Mesopotamia. Isis was a manifestly female figure who symbolized the elongated land called Egypt as it waited to be fertilized by the flooding of the Nile, a river represented by her husband Osiris. Together the couple symbolized the cycle of living and dying, the idea that life returns after death, just as new life sprouts from the parched earth every spring. In that flourishing period the Isis cult grew into a mystical religion that was in some ways similar to the later Christian faith. It had initiation rites that included baptism, and people who underwent them were literally expected to see the light. Those who had been initiated would live on in the Elysian Fields after their deaths, under the protection of Isis, on condition that they had fulfilled the duties laid down, one of which was permanent chastity. The Isis cult was centred on values familiar to us, including self-control, asceticism and a sense of guilt and remorse. The Hellenic world, it seems, was becoming ripe for a religion like Christianity.

Processions were held for Isis, and those taking part carried a wide range of symbols. One of them, Apuleius tells us in his

Metamorphoses

, was the image of a left hand as a symbol of justice. He adds that it was highly appropriate, since the left hand’s innate clumsiness made it better able than the right to symbolize that particular virtue. This indicates exactly what the left hand portrayed: not artful, juridical justice, with its manipulations and complex, logical interpretations, but a sense of justice, the emotional experience of justice, the feeling of fairness and just deserts.

Remarkably, we find something very similar in Judaism. According to ancient Jewish tradition, Yahweh holds mercy and the Torah in his right hand, life and justice in his left. Not only is the left hand once again associated with life, but it also symbolizes justice, as in the Isis cult, except that this time the opposite pole is the Torah, the written law. Justice must therefore be understood here too as a purely emotional conviction that right has prevailed, that things are as they should be, rather than the confidence that certain rules or laws have been res pected. Anyone who has received a parking ticket or been thrown out of a school class on dubious grounds knows that there can be a considerable difference between the two.

Isn’t this contradicted by the fact that the right hand of that same god holds mercy as well? Surely mercy is an emotional business? Not at all. Our intuitive sense of justice has to do with atonement, with a settling of accounts, with revenge. Ultimately it means an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, as demonstrated by sayings such as ‘as you sow, so shall you reap’, ‘on your own head be it’ and ‘good comes to those who do good’. It’s brutish and unrestrained, with no room for empathy or for allowing merciful compassion to serve as justice.

Mercy by contrast puts a civilized, rational brake on our desire for retribution. We might want to tear those who wrong us limb from limb, to hang, draw and quarter them, to tear out their tongues, but instead, entirely rationally, we muster some understanding for their motives and circumstances, consider what the further consequences of vengeance would be and satisfy ourselves with less than our due. Mercy has nothing to do with lovingly stroking the head of a naughty child – that’s simply tenderness or pampering. Showing mercy is a way to interrupt a spiral of violence before it gets out of hand, mainly on rational grounds.

Here the true significance of the contrast between left and right emerges at last: emotion as opposed to reason, things felt but not understood as against analysis and knowledge. left also signifies the things that inevitably happen to us in contrast to the things we control, magic as opposed to skill, and this fits perfectly with its link to health and sickness, life and death. If there’s anything mysterious and unfathomable, anything with a magical charge, then it’s the business of sickness and health. This remains the case today, to judge by the popularity of herbal lore, faith healers and the laying on of hands. And let’s not forget the placebo effect.

Elsewhere too we come upon indications that the contrast between the rational and the irrational represents the ultimate significance of the symbolic contrast between right and left. We need only look at advertising, especially on television. All over the world, left is associated with femininity, right with masculinity. We saw this in Pythagoras’ Table of Opposites, but it emerges in countless other ways too. Think for example of the belief that sperm from the left testicle produces girls and sperm from the right boys. It’s a superstition that goes back to another early Greek philosopher, Anaxagoras, and it survived well beyond the Middle Ages. Over the centuries, a great many men have tied off their left testicle in the hope of conceiving a son.

Even on the other side of the world, people think the same way about male and female. The Maori of New Zealand, to take one example, call the right

tama tane

: the male side.

Tama tane

is also the term for the male sexual urge, for power, for creativity and for the east. The female side,

tama wahine

, has precisely the opposite connotations. Many Bantu tribes in Africa regard the right hand as the strong, masculine hand and the left hand as feminine and weak.

In contemporary advertisements for fashionable luxuries, such as certain drinks, or night clubs and fashion items, the man is generally the smooth, self-assured type who is very much in control. He goes about either in casual clothes of calculated nonchalance or in sharp suits. He drives a classic car of the kind available only to true go-getters, expertly sails a seagoing yacht single-handed, stripped to the waist, or carries a briefcase which clearly contains extremely important documents, indicating that he bears immense responsibility. He’s a man of the world, exuding expertise and self-confidence, a good sport but clearly someone who sets his own boundaries and upholds them.

Women in these commercials are of an altogether different nature. No longer the dumb blondes or gentle, self-sacrificing mother figures of decades past, they take the initiative and dress in tantalizing, shiny lingerie or enchanting but utterly impractical outfits. Sometimes, playfully, they may wear men’s clothing, but in that case they’re redolent of naughtiness with a hint of irresponsibility. Clearly such a woman couldn’t care less about any conventions or boundaries that prove inconvenient. Sometimes, rippling like a tiger, she stalks a man, tempting him into a wild tango. She may even slink towards him across a crowded bar, oozing an aggressive, mysterious sensuality. He goes along with her as far as it suits him, even a fraction further perhaps. She may get to the point of tearing the clothes from his body, although only to make herself seem all the more tempting, or to lead him into a yet more irresponsible game. She goes to extremes, behaves with undisguised hostility towards other equally ravishing women, and regards life as a feast for the senses. If she has ever worked at all, then she probably had something to do with painting or sculpture.

Among the prime examples of this division of roles are the advertising campaigns a Dutch gents’ clothing company called Van Gils has been running since around 1985. The earliest of its adverts each featured a man who in one way or another fell under the spell of a woman. Once, only half covered by a sheet, he was taken in hand by a heartstoppingly pretty masseuse, his suit hanging over a chair just out of reach. Another time a woman seized possession of his suit while he was in the bathroom. Each time the tagline went: ‘Back in control very soon.’ Here we have all the symbolic elements in an undiluted form. Neither the man nor the woman lack courage, but in the woman’s case it’s the courage to let herself go, to allow herself to be led by playfulness and sensuality, whereas in the man’s case it’s the courage to take a calculated risk; he delivers himself to the woman, but not completely. The tagline represents what he’s thinking. A quarter-century later, in 2009, the Van Gils campaign featured a love-making session in an expensive hotel room. The woman is as playful and sensual as ever, elegantly revealed in her black lingerie. The man is wearing his suit this time, and he has the head and hands of an unpainted mannequin. He plays the game, but without baring an inch.

It’s clear what’s going on here. Whether or not we agree with the premise on which they’re based, these adverts are caricatures of deeply rooted associations: the man stands for control and calculation, in short for reason, while the woman represents irrationality, spontaneity and uninhibited emotion. As Camille Paglia would put it, the woman is the natural, irrepressible element, contrasted with the orderly, controlled, cultured world of the man. If we take account of the established links between femininity and the left, masculinity and the right, then everything falls neatly into place. left and right are symbols of nature versus culture, magic versus expertise, overwhelming emotion versus controlled deliberation.