The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (25 page)

As far as the tongue is concerned, our knowledge is extremely limited. It would be a little bizarre to ask large numbers of people to sing songs or recite poems with half their tongue between their teeth, and who can say whether or not it would render up anything useful?

28

Tallying Up

What is it exactly that’s so irresistibly funny about the eternally squabbling cartoon duo Tom and Jerry? Surely it has a great deal to do with the inexhaustible supply of unpleasant surprises, like the door with a brick wall behind it. Less funny was the discovery that medical and psychological breakthroughs of the second half of the nineteenth century were rather like the opening of exactly that kind of door. It was clear that hand preference had something to do with specialization by the two sides of the brain, but it would be a long time before the brain became accessible for direct investigation.

So people resorted to indirect methods, using psychological and statistical research to chart the traits that accompany left-handedness more often than we would expect based on chance alone. Scientists hoped this would at least help to determine whether hand preference was inherited and whether left-handedness was an abnormality, perhaps one that pointed to other problems. Although this would not lead to an explanation of the origins of hand preference, it might perhaps teach us something about the reasons why to this day one in ten newborn babies are left-handed. Over the years this approach has produced an impressive pile of reports and research data.

For practical reasons many such studies focus on groups that already differ from the norm in some way: children at schools for the disabled, people undergoing hospital treatment, residents of care homes or other institutions, prisoners, and pupils with all kinds of problems who have come to the attention of school doctors and psychologists. One major advantage of this approach is that you don’t need to go looking for subjects. You can concentrate instead on groups that tend to live in organized contexts, in buildings that are easily accessed by the staffs of universities, institutes and hospitals. Their lives are regulated by systems in which it’s normal to be investigated, so studying hand preference is a relatively effortless business, and they generally have little to do, which makes them ready and willing to take part in innocent-looking research projects. It’s a welcome diversion, something to distract them from their less than cheering daily routine. Furthermore, all kinds of medical and psychological data are available on such people, so it’s easy to make comparisons. All this has the incidental but far from trivial advantage that the research can be kept relatively cheap.

There’s another reason for concentrating on these particular groups, one that’s at least as important: the existence throughout history of preconceived ideas and prejudices about left-handed people, beliefs reinforced by the discovery of lateral specialization in the brain. Left-handedness is a minority phenomenon, and because aberrations are negative it demands to be corrected almost by definition. This is one of the many ways in which our tendency to think in opposites, in ‘we’ who conform to the norm and ‘they’ who are different, influences our attitude to our fellow human beings.

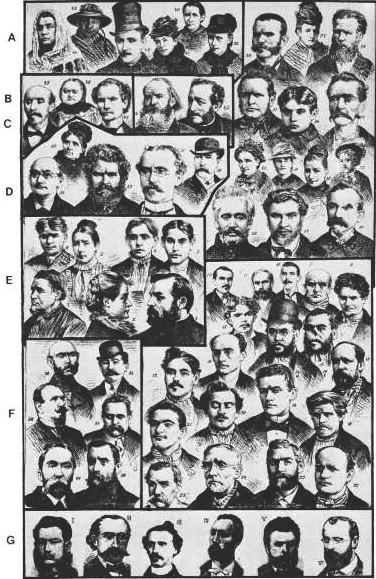

The crudest example of supposedly scientific research in the recent past that was in fact based primarily on unshakable prejudice – and not only in relation to left-handedness – is the work of Lombroso, who believed he could reliably read off character traits and aspects of a person’s make-up such as intelligence, trustworthiness and criminality from external features, including the shape of the face and head, body posture and, naturally, hand preference. Around 1900 he turned his attention to left-handedness and promptly found significantly elevated rates of it among criminals, especially female criminals. His categorization of left-handers as among the more civilized kinds of miscreants was presumably meant as a compliment. No fewer than one in three swindlers and racketeers were left-handed, he said, whereas in respectable people the rate was one in twenty. Murderers and violent assailants, the great skull-measurer claimed, display a far less striking tendency towards left-handedness, with figures of no more than about 9 per cent.

Lombroso’s conclusions turned out to be incorrect whichever way you look at them and his work has long since been consigned to the graveyard of science, but other consciously or unconsciously biased research persisted. In 1911, for example, psychiatrist E. Stier, on behalf of the German high command, carried out research into left-handedness in the army. Stier had published work on the subject before and he believed it was an inherited characteristic particularly common in primitive peoples. This not only reveals the man’s prejudice, it shows he was the kind of academic who paid little heed to facts and figures. We should therefore not be surprised that on average he found only 4 per cent of people to be left-handed, with the exception of the most stupid soldiers, among whom he discovered more than three times as many. Abram Blau, American psychiatrist and scourge of the left-handed, warned young parents as recently as 1961 in a newspaper article: ‘Don’t let your child be a leftie!’ Even the great British child psychologist Cyril Burt had an attitude that could hardly be described as free of value judgements. In his monumental 1937 work

The Backward Child

he characterizes left-handers as follows: ‘They squint, they stammer, they shuffle and shamble, they flounder like seals out of water. Awkward in the house, and clumsy in their games, they are fumblers and bunglers in everything they do.’ Talk about prejudice. A measured assessment is the last thing you’d expect after that.

The faces of German criminals illustrated in Lombroso’s standard work

L’Homme Criminal

. They include shoplifters (A), murderers (E), pickpockets (H) and burglars (I). The rest are all crooks of various other kinds. According to Lombroso there must be around twenty left-handers here.

Lombroso, Stier and Blau aren’t exactly shining examples to the rest of science – no sensible person would take their tall tales seriously today – but Burt is a different matter, since although controversy once surrounded the reliability of his twin studies, he was generally regarded as a meticulous researcher and is still held in high regard. That a serious scientist could allow himself to be carried away to such an extent by traditional prejudices, without noticing that in daily life he came upon so few of those floundering bunglers and squinting stutterers, demonstrates how perfidious prejudices can be and how hard it is to break free of them. Stereotypes undoubtedly had an influence both on the choice of research topics and on the interpretation of the data generated.

Over the past 70 to 80 years many hundreds if not thousands of studies, large and small, have examined the rates of occurrence of left-handedness in specific groups of people. The results are by and large disturbing, at first glance at least. Whatever the abnormality present in the group studied, there almost always seem to be more left-handers than would be expected based on chance alone: stutterers, dyslexics, children with special educational needs, sufferers from hay fever, asthma, allergies and other autoimmune diseases, epileptics, breast cancer patients – in every case they included a remarkably high proportion. There’s even a small study that suggests a clear link with alcoholism, another in which an unmistakable correlation is found with criminal behaviour, and a paper in which left-handedness in the more deprived neighbourhoods of a major American city is associated with heavy smoking.

Just as one swallow doesn’t make a summer, one study doesn’t make a hard and fast rule, even if the media often imply that it does. The results of this kind of research do something else entirely. They indicate the likelihood that an observed correlation between two phenomena is the result of pure chance. If that likelihood is small enough, then the scientist has a significant result and will write an article for an appropriate scientific journal, so that fellow scientists can work out whether or not what he or she says is true. This certainly does not amount to firm proof that the correlation exists in reality, let alone that one phenomenon causes the other. The publication of research results can better be compared with a decision by the police that there is sufficient evidence to arrest someone as a suspect in a criminal investigation. It indicates a reasonable suspicion of involvement, but no more than that.

No study is any more reliable than the assumptions on which it’s based. Errors of logic that creep in while an experiment is being set up, or while the data are being processed and interpreted, make the results as worthless as a car with wooden cylinders under its gleaming bonnet, or a computer with woollen circuits. Worse still, as long as no one brings those mistakes to light, the results will mislead. This is the origin of countless spinach-causes-cancer stories. Carelessness in carrying out experiments has a similar effect, as does the use of instruments that don’t do exactly what a researcher thinks they do, or reliance on assumptions that don’t square with reality. In short, it’s not at all easy to design and implement even the simplest study, and even the most careful, meticulous stickler of a researcher can run into problems with the most danger ous assumption of all: that he’s testing a representative sample.

In practice it’s hardly ever feasible to involve every member of a relevant population in research. Only more or less long-term, hugely expensive population surveys can do that, and they are the exception. They’re usually set up to look at common, fatal diseases such as breast or cervical cancer, and even so they are extremely rare. Researchers usually work with a manageable number of people who are presumed to be representative of the population as a whole, but it’s difficult to be sure whether this is truly the case, if only because no one knows exactly what a normal person is.

The only convincing method is to compile a random sample of the entire population, one large enough to win the approval of statisticians. In practice this is hardly ever possible. For reasons of money, labour and time, the sample group is usually so small that it’s barely statistically valid, and selection is anything but random. All too often scientists resort to students and easily accessible populations in homes and institutions, leaving the general run of the population wholly out of account. An additional problem is that people have to give informed consent before they can be allowed to take part. This too colours the picture.

The key to achieving a dependable result despite all these limitations is repeatability. This is one of the most important reasons why researchers are obliged to publish accurate and detailed accounts of how they developed and carried out their work. Such publishing requirements mean that faults in the design of studies can be pinpointed in retro spect. This is exactly what happened to the scientists who thought they’d discovered that toads are right-handed but had failed to realize that for anatomical reasons the test they’d invented was incapable of proving any such thing. They were rapped on the knuckles a few months after their work was published.

If other researchers using different research subjects with the same approach and the same methods of implementation come up with extremely similar results time and again, chances are those findings are actually meaningful. The likelihood that researchers have made exactly the same unnoticed mistake independently of each other becomes smaller every time the test is repeated. If they make a different mistake on each occasion, then in the long run the distortions this creates will tend to cancel each other out. A stable average result will emerge in which we can have a reasonable degree of confidence.

Bearing all this in mind, if we look at the studies that have linked left-handedness to all kinds of disorders and ailments, it immediately becomes obvious that there are countless reasons for scepticism. One major problem, for example, is the lack of any unambiguous and generally accepted definition of left- and right-handedness. Some researchers divide their subjects into two groups, others work by categorizing them as left-handed, right-handed and mixed-handed. Sometimes a person is regarded as left-handed if he performs, or says that he performs, just one task with his left hand, sometimes only if he does literally everything left-handed. Researchers usually present lists of questions, but sometimes people actually have to carry out tasks, while in other cases various dubious dexterity tests are used to compile hand preference scores. One study may involve a checklist of only three tasks, whereas another may introduce ten or twelve criteria. A researcher may refuse to take account of which hand a person uses when writing because of the possible influence of social pressure, while a fellow researcher takes the writing hand to be the most important indication. In theory at least, a person who is defined in one study as right-handed might quite possibly be cate gorized in another as left-handed.

There are a great many flashes in the pan in the form of studies that are never repeated. This is understandable. Research on hand preference is not a high priority, and many test subjects need to be recruited before you have enough left-handers to render up reliable figures about small differences in the relative proportions of left-handed and right-handed people.

The effort required to recruit all those left-handed research subjects is a real snake in the grass. You need a group large enough to allow you to extrapolate from your findings. As a result the issue is very often turned on its head. Instead of investigating whether a given disorder occurs remarkably often or remarkably rarely among left-handers, a readily available group with a particular characteristic – prisoners, dyslexics, cancer patients – is studied to see whether it contains more left-handed people than are found in the general population. It’s by this route that practically all the reported connections with ailments, aberrations and inadequacies have been found. On the few occasions when tests have been done in the opposite direction, it’s never proven possible to find any significant correlation. Time and again, the results produce the paradoxical conclusion that people who suffer from a particular disorder are more likely than average to be left-handed, even though left-handers are not any more likely than the general population to suffer from that same disorder.