The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (17 page)

21

The Circle Dance of the Alphabet

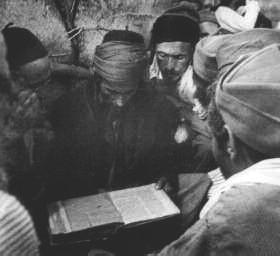

In April 1949 a remarkable photograph cropped up in various places around the world, showing a group of Yemeni Jews in a reception camp near the seaport of Aden. They are on their way to Israel and they’re all crowding around a Torah. One has the book in front of him in such a way that he can read it in the normal Hebrew manner from right to left, in lines that run from top to bottom. A second is sitting off to the left of the Torah and is therefore forced to read columns of text that run from top to bottom and from left to right. In the foreground another man is reading the text upside down and the rest too, from various angles, are doing their best to look at the pages.

It’s difficult for people in the rich world to imagine, but clearly these gentlemen are at ease with their unconventional reading positions. A scarcity of books, such that one copy had to be shared between three or four schoolchildren, had caused them to learn to read from various angles. Why not, in fact? There’s no law of nature that says, for example, that our letter A must stand with two feet on the ground; in fact, there was once a time when it didn’t. Originally, in the Phoenician alphabet, it was upside down, forming a pictogram of an ox’s head with horns. Later it came to lie on its side and only when the Greeks adopted it did the two ‘horns’ come to rest on the ground.

We may wonder how the men in the photograph wrote, assuming they had learned to do so. Did they orientate themselves in the same way as for reading, or did they write in the standard Hebrew manner, in horizontal lines from right to left? Did this affect how well they could write? The profound effect that the direction of our writing has on our observation of reality has led many people to conclude that, far from being a matter of chance, it’s determined by nature, a form of behaviour that somehow flows from our genetic inheritance, probably connected in some way to the predominance of right-handedness. It’s generally assumed that right-handed people naturally prefer to write from left to right, left-handers in the other direction.

| Different perspectives on a copy of the Torah. |  |

This reasoning, to which many adhere, teachers in particular, suggests that ours is a fundamentally right-handed script. Arguments have been put forward in support of this claim. It is said to be more natural to use a right hand to write from left to right because it will then move away from the body. This conviction is in turn based on the assumption that movements away from the body are more natural than movements towards the body, although it’s far from clear why this should be the case. A second argument often advanced is that right-handers who write from left to right pull the pen across the paper, whereas if they write from right to left they are required to push it, which inevitably leads to smudges, and to bent and split nibs.

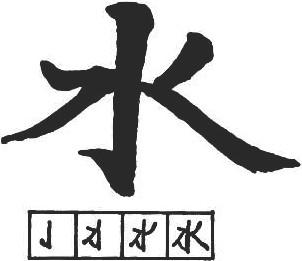

Anyone who replies that people elsewhere in the world are as predominantly right-handed as we are but for centuries have written from right to left to the full satisfaction of all concerned are told this is merely an illusion. The example given is almost always that of Hebrew. In that language, although the letters are written one after the other from right to left, each letter is formed from left to right. This is also the reason, people go on to say, why Hebrew is still written in block letters and does not have a flowing, joined-up form. Sometimes Chinese is brought to bear as well, a language traditionally written from top to bottom. The Chinese too, after all, form each character from left to right. The rules for forming letters and characters in these languages are said to indicate that basic biology will always show through, even in the case of right-to-left handwriting: people are naturally inclined to work from left to right.

We will return later to the push and pull movements performed by left- and right-handed people, and to those bent nibs, inkblots and smudges, but this last assertion – that even if the script runs from right to left or top to bottom the individual letters or characters are formed from left to right – is undeniably true in the case of Hebrew and Chinese. Yet it does not at all follow that there’s anything natural about writing from left to right, or even that letters and symbols are always formed in that direction. To see this we only need to step across to Israel’s neighbours, the Arab countries. Arabic is written in the same direction as Hebrew, but it’s a joined-up script with letters written in a fluid motion from right to left. Block letters don’t exist in Arabic. Of course Arabs are no less right-handed than we are, in fact in Arab cultures the left hand is subject to a far stricter taboo than in the West. As a young Arab you can forget about trying to write with your left hand. It’s simply not tolerated.

| The Chinese character shui , water. It is composed stroke by stroke from left to right. |

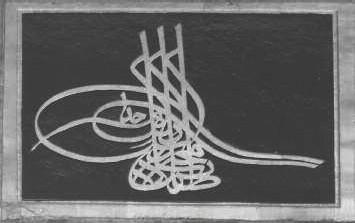

Arabic is a rather unusual form of writing, a script with a hugely important calligraphic tradition that has its origins to a great degree in the Islamic ban on the representation of the human figure, a rule that in earlier times was strictly enforced. Calligraphy was one of the ways of creating visual art and decoration within those limitations, and a wide range of decorative forms of handwriting were developed to that end, in which the priority lay with beauty rather than readability. Of course decorative writing exists in Latin script too, as seen in those curlicue letters we like to use on charters and diplomas, but the practice was taken a good deal further in the Arab world.

Most forms of everyday Arabic writing stand out from other types of script in their elegant, flowing style, and they are usually written not on the line like Latin script but around the line. Each word dances from just above the line on the right to just below it on the left, like an endless series of waves meeting the coast. The shape of many letters varies significantly depending on the place they occupy between neighbouring letters.

Arabic script was impossible to produce satisfactorily on a typewriter, since it could not be reduced to a straight line of unchanging letters. Generally speaking this also applied to the typesetting machines used in the printing of works in Arabic. It was a limitation that had all kinds of deleterious effects on the Arab world, which the Enlightenment passed by and which in any case did not lay great emphasis on reading and writing. Not until about 1990 did the computer start to overcome the problem. Modern word processors and computerized typesetting systems can produce perfectly respectable Arabic script.

Monogram of the Turkish sultan Mehmet II, a masterpiece of calligraphy from 1223 that pays little heed to legibility and is all the more beautiful as a result.

Would it not be ironic if Arabic, of all languages, had been written for many centuries contrary to the ‘natural writing direction’ – a script so much geared to handwriting that it can be achieved mechanically only by advanced computer programmes? If that were the case, could it ever have spread through large parts of Asia, from Turkey to Indonesia, and across all of North Africa and most of East Africa? Could it have maintained its hold so effortlessly right up to the present day in the entire Arabic-speaking world from Morocco to Iraq, in Iran and in Pakistan, without ever being replaced by a less ‘unnatural’ alternative? It seems highly unlikely.

The improbability becomes even greater when we consider that our alphabet and Arabic script both emerged in the distant past from the same northern Semitic tribe to which the Greeks belonged. The Greeks, who with their block letters presumably had far less difficulty with their supposedly unnatural direction of writing, began to write from left to right in about 800

BC

. Three centuries later that became their sole norm. So why would the choice have been made to write joined-up Arabic in the ‘wrong’ direction?

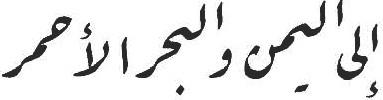

In reality Arabic is not awkward to write at all. Its dancing, artistic character arises from an optimal adjustment to the requirements of writing from right to left with the right hand. If we take a close look at the dance-steps that Arabic writing makes, then we see that each word is written on a slight diagonal from top right to bottom left. Each new word starts well above the line. Given that the paper is perpendicular to the body, this also prevents the right hand from brushing across the letters it has just produced and smudging them.

An example of Ruq’a, an Arabic script in daily use in the Middle East that is excellently suited to right-handed writing. Each word is written from right to left on a falling line.

The fact that the two most widely used types of script, Arabic and the group that consists of the Latin, Greek and Cyrillic alphabets, are written opposite ways around is far from the only evidence that there’s no such thing as a natural writing direction. Many different ways of writing have been used in the past. Until the sixth century

BC

some Greek inscriptions were written boustrophedon style, most commonly those in either Etruscan or Demotic, a script that in Egypt developed from hieroglyphics. Boustrophedon means roughly ‘turning the ox’ in classical Greek and refers to a way of writing in which the lines were written alternately from left to right and from right to left, the way a farmer ploughs a field. Sometimes individual letters were reversed as well, sometimes not.

Boustrophedon is not at all illogical. Instead of moving the hand and the focus of the eye all the way from one edge of the writing surface to the other every time you start a new line, you read and write from the point where the previous line ended. Since the system never spread much further and soon disappeared from Greek, we can assume that this advantage did not outweigh the disadvantage of dealing with two reading directions at the same time. This probably has to do with the fact that in boustrophedon script the word-images – and in some cases even the letter-images – are not constant. The same word can appear in mirror image depending which line it is on. The word Mirror can suddenly appear as rorriM or even . If we spell out the word letter by letter, this is not much of a problem, but that’s simply not the way we read. Once we’ve learnt to read quickly and fluently we recognize entire words at a glance, which in a boustrophedon text is at least twice as difficult.