The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (32 page)

35

The Things That Things Make Us Do

According to the ancient Greeks, at the beginning of time, before human beings came on the scene, the universe was ruled by the primeval god Uranos. His sons were the Titans, strapping lads of whom the youngest was Cronus. The rebellion of Cronus against Uranos marked the start of the everlasting rivalry between fathers and sons. It’s a struggle that every son, when he eventually becomes a father, will at some point lose.

In those untainted, pre-worldly times, some less than subtle things happened. Take the way Cronus stripped his father of power. He took an adamantine sickle in his left hand, castrated his sleeping father and threw the sickle into the sea along with his father’s crown jewels. Then the ambitious youth banished his unmanned begetter to the underworld for ever, taking his place on the throne of heaven until the day came when he in turn was violently dethroned by his son Zeus. Out of Uranos’ crudely severed testicles and the sea, Aphrodite was born, the goddess of love. So Cronus’ horrific deed brought forth something good in the end.

Like all myths, this story explores life’s eternal themes, the instincts we all obey. What makes it unusual is the significance it attributes to the left hand. Sickles are agricultural instruments that cannot be switched from one hand to the other and have always been available exclusively in right-handed versions. Cronus’ use of his left hand must therefore have symbolic significance. Maybe it was a way of emphasizing the unholy nature of his deed, a rebellion against the established order.

What goes for sickles goes for most other tools, appliances and machines: they are all made for use with the right hand, leading to thousands of minor problems for left-handers. Knives with one flat side are consistently sharpened in such a way that a left-hander will tend to cut on a slant. Scissors have loops in their handles that are the wrong way round for left-handers, causing painful rubbing, even blisters, and they are assembled the wrong way round as well. When considerable pressure needs to be applied, the blades, instead of being pushed together, are forced apart, so the material between them buckles – right-handers encounter this phenomenon when they try to cut the nails of their right hands. Measuring jugs with marks on the inside are impossible to read if used with the left hand; indeed, there’s a whole series of ordinary kitchen utensils that are not so ordinary for left-handers, including cork screws, saucepans and gravy spoons with pouring lips, and of course can openers. Then there are brooches and badges with pins that open the wrong way. A fish slice, fish knife or cake fork with a cutting edge is completely unusable for a left-hander, as are those modern plastic throw-away forks with serrations along one side. And rulers. The numbered marks run from left to right, forcing left-handed people to draw lines towards the zero, a source of irritating errors.

It’s astonishing how many things are designed for right-handed use. The arm of an old-fashioned record player, for example: it’s always on the right, as are the slots in coin-guzzling machines such as parking metres and juke boxes, or the grooves along which you swipe your debit card. The ignition lock on the steering column of a car, wherever you are in the world, is on the right, as are the most important knobs on audio equipment, such as the volume control. The buttons on monitors and television sets, if they’re not at the bottom, are to the right of the screen. This seems innocent enough, until you realize that as a left-hander you have to reach across in front of the screen to adjust the colour contrast. Film and video cameras are shaped in such a way that they can be carried on the right shoulder only and have to be used with the right hand. A stills camera is operated by pressing a button that’s always on the right.

There’s more. Irons with those flex-holders that are supposed to be so handy are a complete disaster. Suturing materials used in operating theatres and first aid posts are designed for right-handers, not to mention the rest of the equipment. Left-handed seamstresses and tailors find that the controls on sewing machines are on the right, and that a great deal of discomfort arises from the fact that they insert pins the other way around. When those pins have to be taken out of the material while it’s being stitched they inevitably have their heads towards the stitching foot, making them extremely hard to remove.

Electric drills have a blocking button, so that the trigger doesn’t have to be held in all the time. It’s always on the left side of the handle, which makes it completely useless for a left-hander – he switches that function off again with the palm of his hand. Downright dangerous are handheld circular saws, electric hedge trimmers and chainsaws. They can be used by left-handers only in a thoroughly irresponsible manner. Unfortunately the truly clumsy left-hander will be the one who fails to realize this. The situation is no better in industry. Factory machine tools and control panels always have buttons and knobs designed for use with the right hand. Sometimes even the emergency switch isn’t replicated on the other side.

Particularly odd is the way our clothes are made. In our traditionally male-dominated world, men’s clothing is buttoned and unbuttoned using mainly the right hand. Any man who breaks his right arm will discover that his generally so humble and cooperative flies have turned into an unmanageable, capricious monster. Women’s clothing does up the other way. This must be a consequence of our deep-seated tendency to divide and polarize. It condemns the great majority of women to a lifetime of struggling to button their clothes.

This may explain one of those bizarre differences between men and women. Men always unbutton their shirts before taking them off. Women approach the task differently. They undo the absolute minimum number of buttons and then pull their blouses or cardigans over their heads. If you ask them why, they say it’s too much trouble to undo and do up all those buttons. Ninety per cent of them are probably right: it’s much harder with your non-preferred hand.

Leaving aside the fact that the numerals are on the right side of the keyboard, the digitalization of the world has brought a number of real blessings. In the paper era the counterfoils in chequebooks always presented a particularly annoying obstacle to left-handed people. The fewer cheques left over, the lower the writing surface fell below the pile of stubs on which the left-hander was forced to rest his or her hand. Occasionally a bank might be willing to provide reversed chequebooks on request.

Many counters and ticket offices have been replaced by websites. This has made life easier for left-handers in one way at least. We have largely been relieved of those pens on chains that organizations obligingly placed on their counters. The chains were always anchored to the right, so that when the pens were used by left-handers they stretched right across the form that needed filling out. And the chains were often so short as to make the entire operation impossible.

Another boon is the disappearance of telephones with the receiver attached by a flex. It was always fixed to the left side of the phone so that a right-handed person could easily dial or tap in a number and then have his writing hand free. That flex perpetually got in the way of left-handers.

Left-handed people always adjust amazingly well. They use their non-preferred hand much more than right-handers do and so become better at it. Left-handed implements are occasionally available, mainly in the kitchen goods and writing supplies sectors, but they’re always hard to find. The only left-handed tools that are fairly readily on offer in the better ironmongeries are scissors.

There are good reasons why availability is extremely limited despite a theoretically enormous potential market of more than half a billion people worldwide. Generally speaking, by the time a left-hander discovers that a left-handed version of an article is available, he’s already invented a strategy for dealing successfully with a right-handed model. Perhaps more importantly, anybody who gets used to working with a special left-handed tool will never be able to wield one belonging to someone else, the boss for instance, with the same degree of dexterity. So for a left-hander there’s only a limited advantage to be had, with the exception of things that are used by just one person in one place, or are easy to carry around. In general a left-handed person will prefer to make do with the less than ideal right-handed version.

This usually works fine. With good quality scissors the paper or fabric that’s being cut will buckle only if considerable pressure is applied. A reasonably practical solution is to use large, good-quality scissors for every cutting task. Only at nursery school, where children are given those awkward, round-tipped toy scissors, do left-handers find themselves completely stymied. A ruler, as we have seen, is perfectly usable for drawing a line of a specific length if you move your pencil towards the zero. That’s not an ideal solution, but it does work. It’s possible to compensate for the absence of left-handed versions of tools and utensils in a myriad of different ways.

There are certain circumstances in which making do is not acceptable, where nothing less than the optimum is good enough and money is no object. Architects, engineers and people trained in technical drawing, for example, traditionally used left-handed or right-handed drawing tables. Happily, equipment for dentists and dental hygienists is available in versions for left- and right-handers, and the same goes for the layout of operating theatres, which can be adjusted to suit the surgeon. In the medical world, much thought has been given to the hand preferences of those who probe, prick and cut us, and there have been debates about and research into the effects of left- and right-handed surgery on the success of specific operations.

Still, the ease with which left-handers make right-handed equipment their own and the care taken in the medical world do not alter the deplorable fact that most ergonomists and industrial designers have a thoroughly nonchalant attitude to the interests of left-handed people, even when the consequences can be dangerous. It must surely be possible to invent a neutrally designed or easily reversible hedge trimmer. Of course there’s no apparent call for one; no left-hander would have the audacity even to inquire whether such a thing existed, since in his experience the answer has always been no. There will never be any demand without supply.

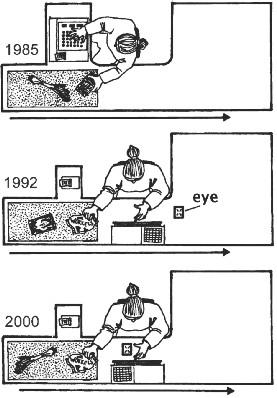

Incidentally, this lack of creative interest and economic incentives has nothing to do with discrimination against left-handed people. Designers and ergonomists only tinker at the edges, they never stop to think about the business of hand preference more generally, as became clear when the electronic till was introduced into supermarkets in about 1990. The cashier no longer had to key prices into a cash register; she only had to pass each article over the electronic eye that’s become such a familiar feature of shopping.

It was a laborious affair at first. If anything it was slower than the old method, since many items had to be swiped across the eye several times before the machine would register the price. Cashiers thought at first that the eye must be dirty. Everywhere spray-bottles of glass cleaner appeared next to the till and cashiers sat there diligently polishing their electronic eyes. It hardly helped at all, since dirt was not the main problem. A lack of thought during the design process had produced an electronic till that was ideal for left-handers and unsuitable for 90 per cent of cashiers.

The old-fashioned supermarket till with its cash register was laid out so that the cashier sat with items on the conveyor belt arriving to her left. She picked up each article with her left hand and worked the till with her right. For left-handed people that was a trial, but it was the best conceivable arrangement for the right-handed majority: the left hand merely slid the purchases onwards, while the fine work was done by the preferred hand. With the arrival of the electronic eye the cashier’s chair was turned through 90 degrees so that she sat facing the side of a surface set at the end of the moving belt, which now stretched away to her right, with a cash tray in front of her along with a keyboard for entering the prices of unmarked items. The electronic eye was placed off to her left, since there, well past the end of the conveyor belt and the cashier’s legs, was where most space was available.

| Comparison of supermarket tills with the electronic eye. |

This seemed logical, but it had unanticipated consequences. Suddenly the shopping no longer arrived at the cashier’s left hand but at her right. That wasn’t a problem in itself, but it meant that the tricky business of making the electronic eye respond had to be done on the other side, with her left hand. Most people were none too good at that part of the operation. Nowadays the eye is no longer positioned away to the left but always straight in front of the cashier.

36

Writing and Other Useful Handiwork

‘Oh,’ the eloquent sixty-year-old said over his beer. ‘Yes, I’m left-handed, but at school they taught me to write with my right hand. And that was fine too. No problem.’

‘But now you write with your left hand. You even drink with your left!’ I slipped the beer mat on which he’d just scribbled his email address into my inside pocket.

‘Yes ... But at first I had to write with my right. So I just got on with it. Until I was thirteen. Then a teacher told me it was okay for me to write with my left hand if I wanted to, so I switched.’

‘I see. So you’re one of those people who were forced to write right-handed. Didn’t it bother you? We’re always being told that children start to wet the bed and so on, and stutter.’

‘Nah ... Not a problem. I can’t remember anyone forcing me, really. I always enjoyed going to school. Yes ... But I did have a terrible stutter, when I was young.’

‘You? Nobody would think so now. You got over it all right!’

‘Yes ... It lasted until about the time I left middle school. Until I was thirteen, then it just went away of its own accord.’

‘Until you were thirteen ...’

‘Yes.’

‘When you started to write left-handed?’

‘Around then, yes, I think so.’

‘Might there be a connection? You started writing left-handed and promptly stopped stuttering?’

‘Well I’ll be damned. Never occurred to me. Wow. You know what – that could be it!’

Left-handers often come up with intriguing stories like this about their educational experiences, especially in primary school. As children they run up against a great deal of incomprehension and ignorance from teachers. They have to conform to a norm that’s alien to them, or they’re left to their own devices but continually told they don’t come up to scratch. It seems they learn to overlook many things, the way this particular drinker never made a connection between his miraculously vanishing stutter and being forced to write with his right hand, and simply carry on undaunted.

Instead of waiting for help they look around for solutions on their own initiative, with such success that in no time they develop into perfectly normal pupils. Ask a teacher to divide a pile of homework from a school class he doesn’t know by sex and he’ll carry out the task whistling and with a fair degree of accuracy. Ask him to put work by left- and right-handers into separate piles and he won’t know where to start. After a year or eighteen months left-handers are able to perform even that difficult trick of writing legibly, whether with their left hand or their right, just as well and as quickly as their right-handed classmates, despite the additional obstacles they face and the back-to-front education they receive.

Nonetheless it’s unpleasant to have a teacher force you into all kinds of contorted postures your body is reluctant to adopt. You’d think the experience would inevitably leave its mark, but it’s impossible to find solid evidence for the stuttering, bedwetting and other nervous disorders said to accompany being forced to write with the right hand. Still, such stories are heard so often that we can’t simply dismiss them, especially when they’re told by left-handers themselves.

Only a few decades ago it was still virtually universal practice to force schoolchildren to learn to write with the ‘correct’ hand. Enlightened teachers who allowed left-handed children to develop naturally, even perhaps managing to give them a couple of useful tips, were rare. Although excesses such as the strap or the tying of the left hand behind the back have been banned, the situation is not much better today. Even now in the modern Western world, children are all too often subjected to subtle pressure to give writing with the right hand a go. It would be better that way. Pedagogical wisdom has it that more than half of all left-handed children suffer from a secret ailment called ‘habitual left-handedness’ – they’re not really left-handed, they’re just pretending to be. The rascals! A characteristically right-handed form of concern about the delicate soul of the left-hander is common too; left-handed children are regarded as suffering from a sense of being misfits in a right-handed world. How treating them as children with special needs and an unfortunate natural preference could possibly help, goodness only knows. Another ineradicable myth is that our form of writing is so geared to the right hand that it’s impossible for left-handers to master. Millions of left-handers furnish evidence to the contrary every day.

All these worries among educationalists are absolute nonsense, there’s no other word for it. Anyone who has been left-handed since childhood knows that by the time a school pupil starts to learn to write his habits are firmly ingrained. Those in whom hand preference is not yet fixed but who eventually, despite all the right-handed models and examples they see, opt for the left hand are apparently not too bothered by the experience. Either that or they have quite different, serious problems. True, if you’re left-handed you may sometimes be bullied as a result, but the same, or worse, goes for the colour of your hair, your accent, your name, the braces on your teeth, the shape of your nose, the brand of your clothing, your eccentric mother, your test scores and an infinite number of other things. No one ever goes to a social worker or a psychiatrist complaining of left-handedness.

The true reasons behind attempts to get left-handers to mend their ways have little to do with worries about their success in learning to write and far more to do with conformism and a misplaced desire for order. A left-hander disrupts the uniform image of the ideal classroom filled with children quietly beavering away, so he or she is forced to conform: all children must sit neatly two by two in rows, all with their arms folded, or all writing with the same hand. Left-handers create further insecurity by confronting teachers with their own incompetence, and teachers react by plunging their heads into the sand. They try to arrange things so that it seems as if the left-handed child doesn’t exist. The more authoritarian the education system, the stronger this tendency towards denial. The more pressure there is to conform, the harder life is made for left-handers.

No one says this aloud, of course. Officially it’s all about how the poor left-hander will benefit. The most popular argument presented for making children switch hands in learning to write is that dreadful hooking of the wrist. It’s always assumed that left-handers make a smudged mess of their written work because they wipe the side of their hand through the wet ink, and because they can’t see what they’re writing because their fingers get in the way. This is assumed to lead to efforts to solve the problem by writing with a strange, crooked claw curled over the top of the line: the hooked hand. But this argument cuts no ice either.

Two variations on that dreadful hooked hand.

There are certainly a good many left-handers who write with a hooked wrist, often producing perfectly neat handwriting, but anyone who takes the trouble to look will see that a good many right-handers write in a similarly hooked manner. This seems bizarre, since it’s impossible to imagine a reason why a hooked wrist would be comfortable or effective for anyone. Yet it is quite common. If you examine the way adults wield a pen you’ll soon notice that there are ten or more ways in which people hold the thing. They include many that are almost painful to watch. Left, right and centre you’ll see pens clamped between three or even four clenched-white fingertips, held between an index finger and a middle finger and resting high up against the palm, or grasped in hooked claws of every shape and description. Left-handers don’t seem to adopt improbable writing postures any more often than right-handers do. There’s only one possible conclusion: generally speaking the teaching of writing isn’t what it ought to be, so children are often forced simply to invent approaches of their own, with variable results.

Another ineradicable story frequently heard in the teaching world is that so-called crossed lateral preference is a terrible thing. This is a belief that goes back to old-fashioned ideas about dominant halves of the brain. It used to be unquestioningly accepted that a healthy person’s preferred hand, eye and foot were all controlled by the same cerebral hemisphere. Not only is there no trace of evidence for this, there’s not even a clear connection between hand preference and other preferences, and oddly enough it’s regarded as a problem only in the case of left-handed people. No one tries to convert right-handers into left-handers if they turn out to be left-footed or left-eyed.

Still, we shouldn’t be surprised, because ultimately all this concern is purely for show. If a left-handed child can’t be persuaded to write with his right hand, then in most cases the expert simply gives up and leaves him to his fate. It’s a rare teacher who’ll take the trouble to learn how to present the correct left-handed method. Left-handers are used to this, of course, since as with other activities like knitting or woodwork they have to puzzle out for themselves how to adjust the consistently incorrect model they’re shown. Nothing can be relied on, other than meeting with contempt when they don’t fully succeed straight away. Left-handers include few enthusiastic young seamstresses and craftsmen for precisely this reason.

The worst scenario of all is one in which a left-handed pupil is presented with a supposedly left-handed method of writing. It always comes down to teaching the poor left-hander a handwriting style that leans backwards, based on pseudo-scientific hocus pocus about natural movements and directions. This won’t help the child at all, since the angle of lean is completely irrelevant. Worse still, writing that leans to the left is socially unacceptable. It makes you look odd. Any amount of neglect is better than being thrown from the frying pan into the fire by being made to stand out.

What all this amounts to is that left-handers in schools are still seen as problem cases. Even today teachers talk of ‘tolerating left-handed writing’, as if it were an undesirable habit. Left-handers are always treated as if they have a disorder, a shortcoming. They’re seen as high-risk pupils, almost as if they should be approached only in the company of a school doctor or psychologist. If anything is damaging to the mental health of left-handers and their ability to enjoy life, then it’s this.

Another deep-seated myth is that left-handers tend to produce mirror writing. At school this too is a source of misplaced concern. Outside school it’s generally a straightforward misconception, but it can also be a trick that gains a left-hander a good deal of credit. It’s quite common for left-handers to train themselves when young to produce mirror writing and to develop an ability to do so reasonably smoothly and neatly, some with the left hand, others with the right. It would be no surprise to find that right-handed people can learn just as easily to produce fast, neat mirror writing with their left hands, since this particular trick has nothing to do with the act of writing as such.

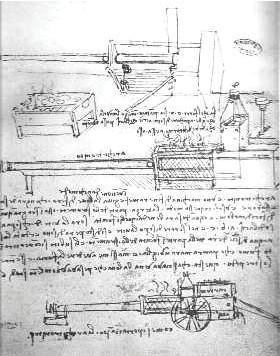

Much of the blame for the development of the mirror writing myth should be laid at the door of Leonardo da Vinci, who was left-handed and in the habit of writing backwards. We don’t know why. That’s a secret he took to the grave with him. It has been suggested it was a way of making his notes unreadable to spies and competitors, but this seems unlikely. His fifteenth- and sixteenth-century contemporaries weren’t so stupid and naive as to be fooled that easily. Leonardo came from a family of lawyers and writing was therefore a prominent aspect of his life, which in a still predominantly illiterate world and in combination with his left-handedness may have been enough to persuade the intractable, restless young Leonardo to make mirror writing his own – for fun, because he could, to be different, and to amaze other people. Sigmund Freud, inevitably, thought it had to do with repressed sexuality. On 9 October 1898 he wrote to Fliess, his pupil at the time: ‘Perhaps the most famous left-handed individual was Leonardo, who is not known to have had any love-affairs.’ Hmm.

| Leonardo da Vinci’s design for a steam cannon made of copper, with notes in mirror writing. |