The Punishment of Virtue (14 page)

Read The Punishment of Virtue Online

Authors: Sarah Chayes

THE BORDER

1838â1898

I

STOOD WEDGED

against a table that took up three quarters of a room at the cramped Pakistani border post. A stumpy, round-headed bureaucrat refused to glance up in my direction. Before him was a vast ledger, its pages rising in symmetrical hills from the center binding and extending at least two feet across on either side. He would glance at it, then page through my passport, rubbing each leaf voluptuously against its neighbor, then run his finger down the hand-printed names and dates in the book. Because of that Achekzai motorcycle ride a month back, which skirted this very border post, my passport lacked the stamp he was looking for. Having not legally exited Pakistan, I was going to have a hard time legally entering it again. I wished there was a way to get to France without setting foot across the border.

That border is a sore subject, and has been for a century. Where precisely the line separating Afghanistan and Pakistan even lies is a subject of violent contention, a lightning rod for seething resentment, animosity, and mistrust between the two deeply entangled neighbors. The porosity I enjoyed in the company of my Achekzai friends; the thoroughfares that insurgents could take across the frontierâunpaved tracks across crags and sandpits, or gates opened by acquiescent Pakistani border guardsâthe repeated Pakistani encroachments, as troops strayed across the line to tumble into firefights with U.S. soldiers, or as officials edged the line forward, moving Pakistani border posts into Afghanistan; all these manifestations of the unsolved conflict would enormously complicate the U.S. mission in southern Afghanistan in the months ahead.

The manifestations are the symptoms of an underlying attitude. During my stay in Quetta, I came to sense that much of Pakistani officialdom thought of Afghanistan as something like the vacant lot behind their house. A place they effectively owned, could unload their junk in, or put to more serious use should occasion require. I started hearing about a notion called strategic depth. In the calculus of their ongoing confrontation with India, it seemed that successive governments in Islamabad postulated Afghanistan as an extension of their territory, land to fade back or retreat to, or base their missiles on, if it ever came to war. And it seemed that much of Pakistani policy in recent decades had been aimed at securing unrestricted access to that territory.

This attitude has hardly been kept secret. Kandahar's telephone exchange under the Taliban, for example, was the same as Quetta'sâwith a Pakistani country code. In 2003, Zabit Akrem received a most unsettling warning, delivered in person by the messenger of a well-known colonel of the Pakistani ISI named Faisan. “Where you are now,” the messenger said, “will soon be part of Pakistan.”

Akrem sent back the reply that Afghanistan has a rather longer history than Pakistan's, and will likely outlast it.

Afghans, meanwhile, nurture a reciprocal proprietary attitude toward much of northern Pakistan. Just about all the refugees I met in Quetta considered the ground under our feet to be part of their native country. I had a hard time taking them seriously, but they were quite worked up about it. Even the scarcely literate would go on at me about something called the Durand Line. Everybody had something to say about it, none of it complimentary. This line, which constitutes Afghanistan's border with Pakistan, was no longer valid, the Afghans kept insisting.

Local lore holds that the treaty establishing the border expired after a hundred years, meaning the line was now defunct. Clearly, the root of the trouble went back to that treaty, to the original drawing of the line. If I was to begin to sort out in my mind the legitimacy of the competing assertions, I was going to have to examine the circumstances that gave rise to it.

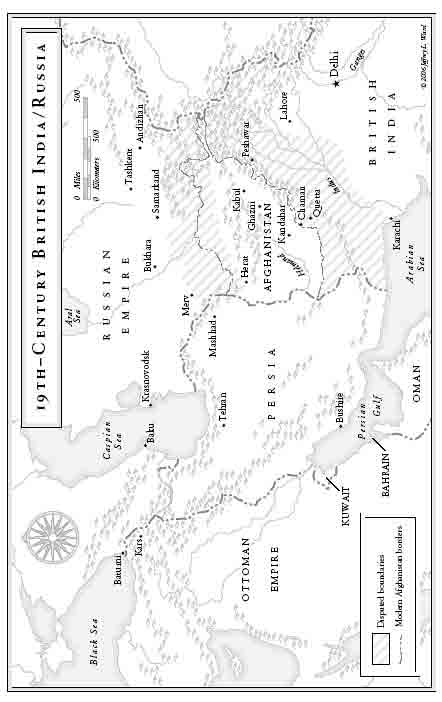

A hundred years, I mused, listening to the Afghan refugees. That puts us in the middle of the Great Game. The term conjured up Rudyard Kipling for me, and not a whole lot else. All I really knew was that it was another face-off between two empires across the Asian landmass, with Kandahar marking the centerline, as usual. I hate the nineteenth century, but I could see I was going to have to get into it. Otherwise, the persistent Pakistani interference in Afghan affairs, and Afghans' burning resentment of a neighbor that shared their religion and their recent opposition to the Soviet colossus, were not going to make much sense.

The two seminal works about the Great Game available in bookstores, when I finally made it home, proved mind numbing.

1

But by shutting out a lot of the details, I could begin to discern the main lines of the story. This border, it emerged, had been a running argument for decades among the amirs of the young Afghan stateâthe successors of Ahmad Shah Durraniâand the heirs to the Moghul dynasty in India, the imperial British.

Throughout the nineteenth century, as Britain extended and tightened her grasp on lands in India, her policy toward Afghanistan, India's northern neighbor, was, in the understated words of the most important Afghan ruler of the day, “subject to occasional fits and changes.”

2

In fact, British policy tacked quite radically back and forth, like a sailboat in a contrary wind.

Britain, at that time, was caught up in a huge worldwide contest between superpowersâthe Cold War of the day. Its rival was Russia. And Russia, during that century, was relentlessly expanding across Central Asia at the expense of Muslim amirs who ruled oasis city-states in such ancient capitals as Merv, Bukhara, and Tashkent.

This Russian expansion, in the view of most British policymakers, was not aimed merely eastward, to push the borders of the czars' land toward the edge of its continentâmuch as the United States was expanding westward across her own continent during those years. The British were sure that Russia had designs on English lands in India too.

The two books I was reading disagreed strongly about the nature of this Russian threat to the English Indian dominions. So did the British at the time.

The conservative Tory Party's assessment of the Russian threat was alarmist, and its reaction to it, hawkish. An imminent Russian danger was the postulate in all the Tory leaders' equations. Their consensus on how best to counter it was that the best defense was a good offense. That is, most Tories judged that the best way to keep the Russians out of India was to move forward

toward

Russia and take over Afghanistan in whole or in part. As it happened, this “forward policy” led the British Empire to one of its most scorching military defeats since the American Revolution.

The Liberal Party, by contrast, was sometimes inclined to make light of the Russian threat. And the favored liberal solution to the Russian problem was rather dovish: to stay put in India, befriending a locally acceptable Afghan leader and allowing him and his fanatically independent people to serve as the subcontinent's gatekeeper. This course effectively halted Russia's military advance on Afghanistan until 1979.

The abrupt tacking back and forth between these two policiesâthe “occasional fits and changes” that occurred every time one party lost an election and the other gained powerâmade the British rather difficult for their Afghan interlocutors to read. This I gathered from my first good primary source for the period: more memoirs, dictated by the late nineteenth-century Afghan amir quoted above: Abd ar-Rahman Khan. He was to play a decisive role in the events, and in the tracing of the famous Durand Line.

Regarding the reliability of British promises, this Amir Abd ar-Rahman once remarked acidly to a British viceroy of India: “I am sorry that I am not a prophet, neither am I inspired to know whether at some future time, if I am in trouble, a Liberal or Conservative Government will be in power.” Abd ar-Rahman found it a brilliant feature of the British constitution that it always provided for “one party or another to put the blame upon when mistakes are made.”

3

The first really appalling mistake the British made in Afghanistan was to interfere directly in the old rivalry between the Popalzai and Barakzai tribesâthe same two tribes that vied for power at the founding

jirga,

the same tribes whose rivalry I would bear witness to so many years later.

When Dost Muhammad, the first Barakzai to displace the founding Popalzai dynasty on the Afghan throne, agreed to meet a Russian envoy in Kabul in 1838, Britain decided to remove and replace him. Though Afghanistan was nominally independent, the overwhelming firepower of neighboring British India made such a decision seem feasible to politicians and bureaucrats in London and the Indian capital of Calcutta. To take Dost Muhammad's place, the British chose an aging and repudiated member of the Popalzai house, an exiled grandson of Afghan founding father Ahmad Shah. The British decided to put him back on the throne he had occupied some three decades earlier. But doing so, and maintaining him there, required the deployment of a garrison in Kabul. This debauched amir emphatically did not qualify as a locally acceptable ruler. He was seen by Afghans as despicably beholden to the English, and their move to install him as a poorly disguised effort to take over the country.

Underestimating Afghan hostility, the British underestimated the type of investment that would be required to control Afghanistan through their puppet amir. This mistake has been repeated by powerful foreign meddlers in small countries, right down to the United States in the twenty-first centuryâbefore my eyes in Iraq, for example.

The British army that escorted the new amir into Afghanistan reached Kabul fantastically encumbered: more servants rode with it than soldiers; the camel train stretched for miles. One account describes a pack of foxhounds among the baggage, and saddlebags straining with angular bulges from crates and crates of cigars.

4

This supporting force was stationed on the outskirts of Kabul, billeted in absurdly exposed barracks: a mile from town, dominated by hills and separated from its own food storehouse.

It did not take long for the disgruntled Afghans, bitterly resentful of the puppet amir and his vast foreign army, to begin exploiting the British position. By late fall 1841, two British envoys lay hacked to pieces in the Kabul bazaar and the hills about the garrison bristled with Afghan fighters and their long rifles, picking off Redcoats who risked a sortie. Without reinforcements from a British contingent based in Kandahar, the Kabul garrison had no hope. A surrender was negotiated with Dost Muhammad's son, who was leading the revolt. It stipulated the total withdrawal of foreign troops from Kabul. The Army of the Indus, the fighting force of the richest and most powerful empire on earth, picked its freezing and starving way up through the hills toward the breathtaking passes on the road that led eastward to Jalalabad and India beyond. There, in those passes, the troop was cut to pieces, despite the treaty. Only a single British fighting man survived, and a few hundred camp followers who were taken prisoner. The force of mighty Britain had been annihilated by a bunch of Afghan villagers.

This exchange was dubbed the first Anglo-Afghan war. It was to burn a sizzling scar into the flesh of British history. Like the story of the founding

jirga,

the tale of it has become a legend for Afghans, to whom it serves as a kind of second founding myth. For the British, it became a painful object lesson in how, in global politics as well as the Bible, pride goeth before a fall. Coming a decade before a bitter and savagely bloody mutiny and uprising in India, the slaughter in the Afghan highlands marked the beginning of Britain's inexorable retreat from empire, which culminated a century later in independence movements across the globe.

The first Anglo-Afghan war has also sent a chilling warning to all other Western powers that have considered following Britain's footsteps into Afghanistan. It is from this story more than any other that the legend of Afghan invincibility was born.

The Barakzai amir whom the British had tried to remove in the first place, Dost Muhammad, returned to Afghanistan. And the Britishâdisplaying as much facility for shifting alliances as the Afghans themselvesâentered into an agreement with him. Under its terms, he would let the British viceroy in India run his foreign policy in return for a yearly subsidy.

A rough peace was thus achieved for some decades. During this time, the frontiers of Afghanistan were never clearly defined. To the south and east, they faded into a kind of tribal beltâwhich even Afghanistan's rulers called a

yaghestan

âseparating their kingdom from the principalities to its south, which were tributaries of British-held India. To the north and west, Afghan lands were subject to repeated attacks from expanding Russia, which had swallowed vast tracts of steppe country, snapped up ancient silk road capitals, and was nipping at the fringes of Afghanistan.

The peace with India was broken, inevitably, by a second Anglo-Afghan war. It erupted in 1878, again because the reigning amir had had the temerity to receive a Russian delegation. Britain had failed in its promise to defend Afghanistan from its giant northern neighbor, and the amir felt he had to open talks with the Russians. A three-pronged British invasion to punish him achieved an easy initial military victory, and the masters of India, for a second time, installed a puppet on the Afghan throne.

Even more openly than before, the British action aimed to move the border of India upward to the line running between Kandahar and Kabul. The Tory hawks were in power, and they wanted to advance

toward

advancing Russia.

And so the British forced upon their new pet amir the Treaty of Gandomak. This was the first legal document to officially sign away swathes of land the Afghans had considered theirs for time out of mind. Quetta and Peshawar, those key outposts on the two roads piercing Afghanistan, went to the Britishâalong with tens of thousands of Pashtun tribesmen who, ethnically anyway, belonged with their brethren in Afghanistan.