The Price of Glory (58 page)

Read The Price of Glory Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

20. French propaganda photograph at a base hospital. Original caption, as printed in

New York Times

in 1916, read: ‘A Soldier Who Has Lost Both Feet. Yet Walks Fairly Well With Clever Substitutes’.

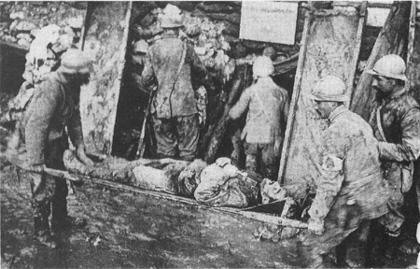

21. French first-aid post at Froideterre.

22. North of Fort Douaumont, Christmas Eve 1916.

23. The glacis of Fort Vaux, 1917 (note the dome of the shattered 75 mm turret).

24. Post-war plaque on Fort Vaux, now destroyed forever by vandals.

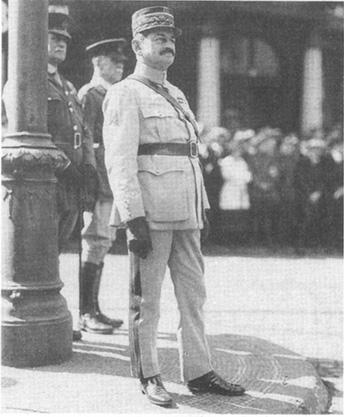

25. General (‘The Butcher’) Mangin, after the war.

26. Ex-Lt. Eugen Radtke, with the author, in Paris, 1963; the first time he had travelled further west than the German lines before Verdun.

EPILOGUE

War is less costly than servitude, said Vauvenargues… the choice is always between Verdun and Dachau.—JEAN DUTOURD,

The Taxis of the Marne

B

EFORE

the Second World War was ended, the sinister battlefield at Verdun claimed one more victim. The bomb plot of July 20th, 1944, against Hitler had just failed and General Karl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel — the German Military Governor in Paris and one of the principal plotters — was on his way back to face trial and certain death in Germany. He asked his guard if he could go by way of Verdun, and on approaching the Mort Homme, where he had commanded a battalion in 1916, he stopped the car and got out. A short while later the driver heard a shot, and von Stülpnagel was found floating in a canal of the Meuse. The wretched man had only succeeded in putting out both his eyes; blind and helpless he was strangulated by the Gestapo.

Except perhaps deep in the memories of a few old men, after 1945 the imprint of Verdun in Germany was largely erased; other more recent nightmares such as Stalingrad had replaced its image. France however has still not got the stimulating but toxic drug completely out of its system. Upon the French Army, desperately and pathetically questing after the sources of

La Gloire

as a panacea to the deadly humiliation of 1940, the influence of this drug became if anything, morally, even more potent. One of Britain’s leading military writers told the author how, shortly after the Second World War ended, he was invited to attend a lengthy seminar in France at the

Ecole de Guerre,

which was dedicated to discussing the lessons of the recent war. But, he said, to his surprise most of the time was spent in discussing the ‘glories’ of the previous war, ‘with particular reference to Verdun’. In a sense the wheel that began to rotate after 1870 had moved through yet another quadrant; once again the ground was as disastrously fertile (and through application of the same kind of manure) as it had been when de Grandmaison and his catastrophic doctrine of

l’attaque à outrance

sprouted from it. The years when Britain was bowing to the inevitable have seen successive weak French Governments goaded on by an army desperate for

la Gloire

— anxious to win a war, any war — to committing themselves irrevocably to military ‘solutions’ in their overseas territories. There was first Syria and Madagascar, then Indo-China and Algeria. Alas, in Indo-China the hidden influences of Verdun overlapped once again into actual strategic considerations. After the first Viet Minh successes in 1951, de Lattre de Tassigny — who in June 1916 had held a position near to the company wiped out in the ‘

Tranchée des Baïonnettes’

— ordered the Delta to be surrounded ‘with a belt of concrete’ unmistakably inspired by Verdun’s ring of forts. A few years later, after De Lattre’s death, an isolated and strategically quite indefensible outpost called Dien Bien Phu was chosen as a fortress where the resurrected French Army would stake its honour and fight, if necessary, to the last man. Dien Bien Phu became a fatal symbol. With superlative courage and total abandon it did fight to the last man. Once again, as the Viet Minh swarmed over the hastily constructed bunkers, the cries of

‘on les aura!’

and

‘Ils ne passeront pas!’

were heard. A few months later Indo-China was lost to France. In Algeria, the same deadly influences could be detected; you do not have to scratch the surface of one of the ‘Colonels of Algiers’ very hard before the word VERDUN is revealed in some combination or other. Is it also just a coincidence that, at the time of the Algerian cease-fire talks, the O.A.S. should have chosen

‘DE GAULLE NE PASSERA PAS’

as one of their favourite slogans?

The ghosts are not allowed to die. Every officer on both the senior and junior courses at the

École de Guerre

is still sent to Verdun for a lecture on the battle; although instructors there freely admit that it had absolutely no relevance to modern warfare. The same is true of the Artillery School at Chalons-sur-Marne. Still the torchlight pilgrimages to the

Ossuaire

continue. The ranks of ‘

Ceux de Verdun

’ are getting a bit thin now, but already they are reinforced by the

anciens combattants

of another war who turn to Verdun, rather than to Bir Hakim or Strasbourg, as a touchstone of faith. And yet another generation is being steeped in the tradition. During the Verdun pilgrimages one is struck by the long silent files of children that throng into the little chapel at the

Ossuaire

to take part in special commemoration services, and in even the smallest villages of France the anniversary of February 21st, 1916, is often celebrated by schoolchildren being marched in procession to the village war memorial.

After 1945, Verdun became again a sleepy garrison town, with one of the vilest climates in France. Early in the morning the bugles calling reveille up in the Citadel still sound thinly over the town, and only an insensitive soul can hear them without a shudder of association. For the tourist who happens to wander into this part of France, the shops of Verdun still display tasteless mementoes of the battle, such as candles moulded in the shape of shells; as indeed, shockingly enough, does a little boutique within the

Ossuaire

itself. But the less obvious reminders are now unlikely to reveal themselves to the casual eye. As you approach Verdun from Bar-le-Duc, without the wreathed helmets on each kilometre stone it would be hard to believe that this narrow, insignificant secondary road was the

Voie Sacrée

along which poured the lifeblood of France in such immense draughts; harder still to imagine its deserted stretches jammed with primitive military transports, bumper to bumper, night and day. At Stenay, the dreary little Meuse town where the Crown Prince and Knobelsdorf had their headquarters, you can, if you peer about, still see, uneffaced after nearly fifty years, German signs left behind by the Fifth Army. At Souilly, there is nothing to indicate that this was once Pétain’s HQ in the first stages of the battle. The

Mairie

is the

Mairie

once more, but if you enter and ask about

le Maréchal

an old soldier working in the secretariat with the gold thread of the

Médaille Militaire

in his buttonhole will delightedly show you the humble office, the worn leather chair.

Closer to Verdun, in the Meuse villages, the signs abound; the viciously heavy barbed wire used on the farms, the wall of the cowsheds made from the thick dugout corrugated iron, the scarecrow using a German helmet. The villages themselves, like those all over France, are still half-empty as the hangover of a war that decimated the peasant population; and (or does one imagine it?) enveloped in a sourness and mournful gloom that is not to be found elsewhere in France, like a blight over the countryside. Still, it is said, there is more danger of infecting a small cut, more tetanus, indigenous to the Verdun area than to any other part of the country. And everywhere, everywhere there are the cemeteries, large and small, French with white crosses, German with black, but all well cared for.

If you sit long enough on one of the forts on the Bois Bourrus, gazing at the superb panorama of the battlefield, perhaps a young

shepherd with a torn trilby will come up to you, and divining your thoughts will remark scornfully: