The Price of Glory (56 page)

Read The Price of Glory Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Militarily, as we know, the Germans solved the problem of the First War deadlock in another way to the French. Being the attackers, they had seen Verdun from a different angle. In its essentials, their problem was that which had faced Ritter von Epp, bogged down amid the limitless horrors of the shellground in the Thiaumont ‘Quadrilateral’; how to prevent an attack losing its impetus and simply becoming ground to pieces by the enemy artillery. Having tenanted Douaumont through most of the Battle, they also sensed rather better than the French what were the Achilles Heels of permanent fortifications. The solution to both problems was provided by the

Panzer

columns of Guderian and Manstein; the lessons of the battle in which they had participated over so many months being lost upon neither of them.

On May 14th, 1940, the

Panzers

smashed through at Sedan where

Louis-Napoleon had surrendered so ignominously seventy years earlier. Exactly a month later German troops again stood before the gates of Verdun, led by a divisional commander who had been three times in the line there during 1916. Once again, briefly, there was heavy fighting on Côte 304 and the Mort Homme, but at 11.45 the following morning Douaumont surrendered — to a battalion commander who had served in the fort himself twenty-four years previously. None of Douaumont’s new gun turrets had fired a shot. A quarter of an hour later Fort Vaux surrendered, and the German

Panzers

rushed on to Verdun. At the Citadel a company of army bakers was taken by surprise as it leisurely baked bread for the men in the garrison, and by the afternoon of June 15th the Swastika flew over Verdun. Its conquest had lasted little more than twenty-four hours and had cost the Germans less than two hundred dead. The next day France’s ‘Men of Fifty’, unable to help themselves, called in eighty-four-year-old Pétain as receiver in bankruptcy. An armistice was requested forthwith.

In his

éloge

to the Académie on being elected to the vacancy created by Pétain’s death — one of the most difficult speeches any Frenchman could have been called on to make — André François-Poncet recounted a parable of Croesus and Solon. Croesus finds Solon weeping and asks why.

I am thinking [came the reply] of all the miseries that the Gods are reserving for you, as the price of your present glory.

Seldom have the elements of Classical Tragedy been more poignantly arrayed than in the last years of Pétain. We see the old man, about to retire twenty-six years earlier to the cottage at St. Omer, now called back in his dotage to assume a responsibility Frenchmen in their prime quail before. The deep-rooted pessimism and bitterness towards Britain surges to the fore; and who indeed in France in the summer of 1940 does not believe that Britain will have ‘her neck wrung like a chicken’? The huge majority of Frenchmen are solidly behind the Hero of Verdun, the man who saved the French Army in 1917 (though, in five years time, many crying ‘traitor’ will conveniently try to forget this). Once again, he is the one man the Army will venerate and obey. Only an eccentric handful, brave to the point of folly, rallies to the Cross of Lorraine raised by Pétain’s former subaltern and erstwhile admirer, Charles de Gaulle.

In vain the Marshal believed that France’s conquerors, being themselves soldiers, would grant her an honourable peace. Pressed by Hitler to total, dishonourable collaboration, he resisted, but had little to resist with. The wily Laval treated him contemptuously as an ornamental front to cover his own ambitions, presented disastrous documents for him to sign late in the evening when his old mind was befuddled. But never was he completely Laval’s or Hitler’s man. Derided, misguided, isolated and betrayed he stayed on at his invidious post; ‘If we leave France now, we shall never find her again,’ he said repeatedly. Above all he stayed in the apparently genuine belief that somehow he alone stood for the safety of the million of his beloved soldiers captive in Germany. In his name, things were done by Vichy France that shocked the world, and especially her former Ally; but how much worse might it have been without that aged hand at the helm? Steadfastly Pétain refused to give Hitler bases in Algeria or surrender the French fleet. Though battered, his honour remained intact, accompanied to the end by a certain tragic nobility; fifty French hostages are to be shot, eighty-six-year-old Pétain offers himself in their stead as a single hostage.

Finally, as the Allies landed in North Africa, Hitler, breaking his word, invaded Unoccupied France. ‘Fly to Africa,’ the faithful Serrigny urged Pétain. No, he replied. If I leave, a Nazi

Gauleiter

will take over, and then what about our men in Germany? ‘A pilot must stay at the tiller during a tempest…’ You are wrong, replied Serrigny, reproaching him gently:

You think too much about the French and not enough about France.

Victorious, de Gaulle returned to France; Pétain was spirited away to Germany by the Nazis. As the Third Reich collapsed, alone of the Vichy survivors he begged to be allowed to return to France to face trial.

At my age, there is only one thing one still fears. That is not to have done all one’s duty, and I wish to do mine.

Through Switzerland he returned to France. He was met by General Koenig. He put out his hand. Koenig refused to take it. By edict of the man who had once applied to join the Regiment he commanded, and to whose son he was godfather, Pétain was placed on trial for his life, clad in the simplest uniform of a Marshal of France, and wearing just the

Médaille Militaire

— the only decoration shared by simple soldiers and great commanders. Urged by his lawyers to take his baton with him into court, Pétain replied scornfully ‘No, that would be theatrical.’ At the beginning of the trial he made one simple, dignified statement to the French people over the head of the Court, which he insisted had no power to try the Chief of State. Modestly he outlined his career in the service of France, ending:

When I had earned rest, I did not cease to devote myself to her. I responded to all her appeals, whatever was my age or my weariness. She had turned to me on the most tragic day of her history. I neither sought nor desired it. I was begged to come. I came. Thus I inherited a catastrophe of which I was not the author… History will tell all that I spared you, whereas my adversaries think of reproaching me for what was inevitable…. If you wish to condemn me, let my condemnation be the last.

Through much of the lengthy hearing he nodded and dozed. As its last witness, the defence produced a general blinded at Verdun, who admonished the court prophetically:

Take care that one day — it is not perhaps far distant; the drama is not yet finished — this man’s blood and alleged disgrace do not recoil on the whole of France, on us and our children.

Finally Pétain spoke his last words;

My thought, my only thought, was to remain with them [the French] on the soil of France, according to my promise, so as to protect them and to lessen their sufferings.

The Court was unmoved. France can be savage in the retribution she exacts, and now, amid the passions of victory and with the wounds of the war still unhealed, the clemency Pétain accorded the mutineers of 1917 is not for him. Guilty of High Treason is the verdict, and the ninety-year-old Marshal is sentenced to death.

Ultimately the sentence was commuted to one of life imprisonment,

and for six years Pétain was confined to the Ile de Yeu, off the Vendée coast; during which time he never uttered one word of recrimination, Regularly he was visited by Madame Pétain,

1

who took a room near the prison. At ninety-two, his health began to decline and Madame Pétain was allowed to move into the prison precincts. Shortly after his ninety-fifth birthday, his mind became no longer lucid and at the end of June 1951 he was freed. Within a month, he died — two days after the ex-Crown Prince — and was buried under an austere tomb in a little naval cemetery. At Verdun, his portrait in the ‘Room of Honour’ beneath the Citadel had been removed; his name chopped out from the head of the wooden plaque that bears the names of the ‘Freemen of the City’. There are no statues — Pétain forbade the erection of any during his lifetime — but in front of the

Ossuaire

the

gardiens

will show you an empty plot of ground where Pétain had hoped eventually to rejoin his beloved soldiers.

‘Perhaps,’ they say, in a questioning tone, ‘Perhaps,

le Maréchal

will be permitted to come back here after all.’

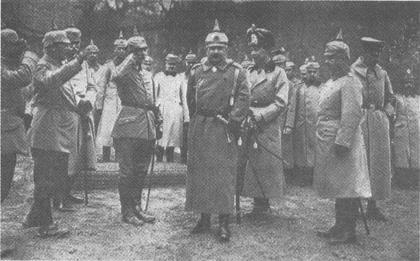

1. The Kaiser at the Crown Prince’s Headquarters at Stenay. Behind the Kaiser, the Crown Prince; on his left, Lt.-General Schmidt von Knobelsdrof.

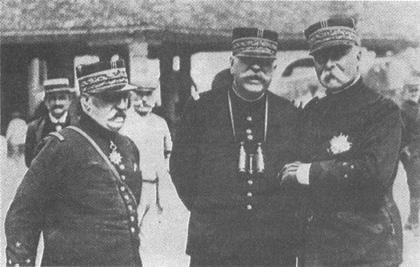

2. General Joffre (centre) and General de Castelnau (left).

3. General Erich von Falkenhayn.

4. Lt.-General Schmidt von Knobelsdorf.

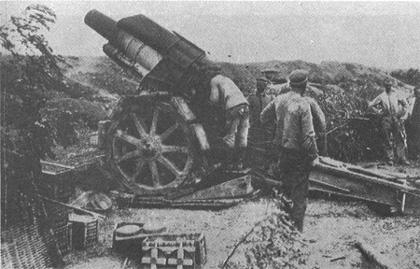

5. German 210 mm howitzer.