The Price of Glory (19 page)

Read The Price of Glory Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

But if the Germans that night, distracted as they were by certain problems of their own, did not realise just how desperate was the French position, they certainly could not guess that they stood on the threshold of their greatest

coup

of the campaign. One of the more extraordinary episodes of the war was now about to take place.

CHAPTER NINE

FORT DOUAUMONT

The fortified places are a nuisance to me and they take away my men. I don’t want anything to do with them.—GENERAL DE CASTELNAU, 1913

The word DOUAUMONT blazes forth like a beacon of German heroism.—FIELD MARSHAL VON HINDENBURG,

Out of my Life

N

O

unit of the German Army was more strongly imbued with regimental pride than the 24th Brandenburgers of General von Lochow’s III Corps. With intense pride the regiment recalled Blücher’s tribute from the Napoleonic Wars: ‘That regiment has only one fault; it’s too brave.’ From the moment of joining the 24th, young ensigns had that drilled into them, plus a dictum of Frederick the Great which had become a regimental motto: ‘Do more than your duty.’ In 1914, the 24th had romped through Belgium, hit the British Expeditionary Force hard at Mons, then marched on to the Marne. As it goose-stepped through France, swigging ‘liberated’ Champagne and lustily singing ‘

Siegreich woll’n wir Frankreich schlagen,’

there seemed no limit to the regiment’s successes. Great had been its indignation when the order came to turn about on the Marne. In February 1916, the 24th had just returned from a victorious campaign in the Balkans where it had helped hurl the Serbs out of Serbia. Now, at Verdun, things had not gone brilliantly so far for the regiment. Stubborn French resistance in Herbebois had led to shaming delays, and administered a bloody nose to the 3rd Battalion, which, to a regiment accustomed only to success, seemed to be almost a disgrace; especially when at the other end of the line there were reports of how well the Westphalian reservists, mere farmers in uniform, had done. As the French line bent and cracked before them, the Brandenburgers strained at the leash after fresh laurels with which to redeem the setback. Ahead there now loomed ever closer the greatest laurel of all; Fort Douaumont. Ever since they had been in the line at Verdun they had had an eye on its great tortoise hump. You could not escape from it. Like a small rodent under the unblinking gaze of a hawk, it made you feel quite naked

and unprotected. At the same time, it beckoned with an irresistible magnetism.

Then, to the 24th’s intense fury, just when the great fort seemed only a couple of day’s fighting away, Corps HQ placed it within the boundary of advance of the neighbouring regiment, the 12th Grenadiers. In their marching orders for February 25th, the Brandenburgers were to halt on an objective about half-a-mile short of the fort, eventually leaving it on their right for their bitter rivals. It was unspeakably unfair.

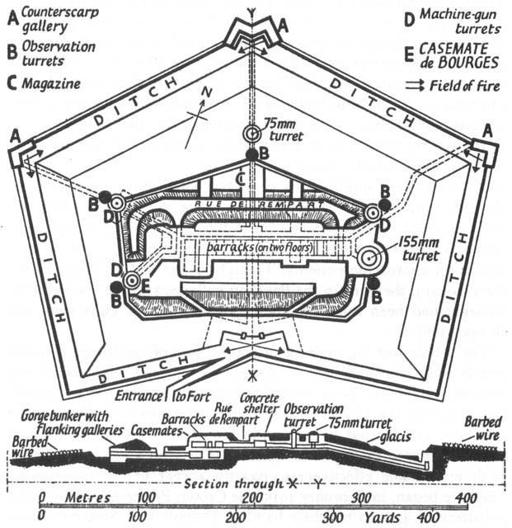

From whatever angle you approached Fort Douaumont it stood out imposingly, menacingly. Hardly a square yard of terrain lay in dead ground to its guns. To the tottering French, it gave the comfortable feeling of having a mighty, indestructible buttress at one’s back. It was, as Marshal Pétain later described it, the cornerstone of the whole Verdun defensive system. It was also the strongest fort in the world at that time — on paper: Started in 1885 as part of the ‘de Rivières Line’, Douaumont had been modernised and strengthened in 1887, in 1889, and again as recently as 1913. The huge mass was constructed in the traditional polygon shape favoured by Vauban, and measured some quarter of a mile across. The outer edge of the fort was protected by two fields of barbed wire 30 yards deep. Behind them came a line of stout spiked railings, eight feet high. Below stretched a wide ditch, or dry moat, 24 feet deep, girdling the fort. At the northern corners were sited concrete galleries, facing into the moat, and at the apex was a double gallery, shaped like a flattened letter ‘M’. These three were (supposedly) armed with light cannons or pom-poms, machine guns and searchlights, so that any enemy climbing down into the moat would be caught by a deadly enfilading fire from two corners. Each gallery was connected to the centre of the fort by a long underground passage, enabling it to be reinforced regardless of enemy fire. Next, on the north side, came the gradually sloping glacis, itself swept by the fort’s machine gun turrets — should the flanking galleries somehow have been knocked out. Even if an enemy survived the traversing of the glacis and penetrated to the Rue de Rempart that ran from East to West across the middle of the fort, he could still be taken from the rear by the garrison emerging out of shelters deep below ground.

At the southern under-belly of the fort, the entrance was protected by an independent blockhouse, also with double flanking galleries. The southwestern approach was masked by a bunker, called a ‘

Casemate de Bourges

’, out of which fired two 75 mm field guns. Meanwhile, the whole of this side of Douaumont also came under cover of the guns of Fort Vaux and other neighbouring fortifications.

Inside, the fort was a veritable subterranean city, connected by a labyrinth of corridors that would take a week to explore. There was accommodation for the best part of a battalion of troops, housed in barracks on two floors below ground level. The barrack rooms had rifle embrasures in the thick concrete of the exposed, southern side, so that each could put up a spirited defence as an independent pill-box; if ever the enemy got that far. As a reminder to the garrisons of their duty, there was painted up in large lettering in the central corridor: ‘RATHER BE BURIED UNDER THE RUINS OF THE FORT THAN SURRENDER.’ But the real teeth of the fort lay in the guns mounted in its retracting turrets. There was a heavy, stubby-barrelled 155 that could spew out three rounds a minute; twin short 75s in another turrret mounted in the escarpment to the north; three machine-gun turrets, and four heavily armoured observation domes. For their epoch, the gun turrets were extraordinarily ingenious; their mechanism adopted, with little alteration, for the Maginot Line thirty to forty years later. Forty-eight-ton counterweights raised them a foot or two into the firing position; but the moment the enemy’s heavy shells came unpleasantly close, the whole turret popped down flush with the concrete. Only a direct hit of the heaviest calibre on their carapace of two-and-a-half-foot thick steel could knock them out, and until they were knocked out they could exact a murderous toll on an approaching enemy. Though, under Joffre’s purge of the forts in 1915, the guns in the flanking galleries and the

Casemate de Bourges

had been removed, these powerful turret guns were still in operation.

The whole fort lay under a protective slab of reinforced concrete nearly eight feet thick, which in turn was covered with several feet of earth. Unlike the great forts of Belgium that had caved in beneath the blows of the German 420s, the concrete roof of Douaumont had been constructed like a sandwich, with a four-foot filling of sand in between the layers of concrete. The sand acted as a cushion, with remarkable effectiveness. Exactly a year before the Verdun offensive began, in February 1915, the Crown Prince had brought up a battery of 420s to try their hand at Douaumont. Sixty-two shots in all were fired, and German artillery officers noted with satisfaction ‘a column of smoke and dust like a great tree growing from the

glacis

of Douaumont’. The fort guns remained silent, so the Germans assumed that Krupp’s ‘Big Bertha’ had once again done its stuff. In fact, though the reverberations and concussion within the fort had been extremely unpleasant, the bombardment achieved little other than knocking away half the inscription,

DOUAUMONT

, over the main gate. (Why the fort’s 155 never returned the fire was quite simple; its maximum range was just over 6,000 yards, which would not have carried as far as the French front lines.) In the bombardments of February 1916, again the German 420s had caused negligible damage. Thus, it seemed — contrary to the pessimism of Joffre and G.Q.G. — that Douaumont was virtually impregnable.

By February 25th, 1916, the attacking Germans had reason to assume that Fort Douaumont had been badly knocked about, but was still likely to prove a stubborn and prickly obstacle. Never could they have guessed that it was both undamaged and — through an almost unbelievable series of French errors — to all intents and purposes undefended!

***

The 24th Brandenburg Regiment’s orders for February 25th were to capture Hassoule Wood, then halt on a line about 750 yards to the northeast of Douaumont. The usual annihilating bombardment had started at 9 a.m. and was to lift to the fort itself, when the attack would begin. The line-up was as follows: 2nd Battalion on the right, 3rd on the left, with the 1st in reserve. On the right flank the 12th Grenadiers (in whose line of march the fort now lay, but who were also to halt short of it), and on the left the 20th Regiment, were to advance simultaneously. But in one of those last minute upsets that occurred so frequently in the First War when runners and word-of-mouth took the place of ‘Walkie-Talkie’, neither regiment received its orders in time. So at zero hour as the barrage lifted, the 24th found itself advancing unsupported. Rather typically, it paid no attention and thrust forward with its usual impetuousness. As luck would have it, instead of finding itself in a nasty trap, the 24th burst into a vacuum left by the Zouaves that had melted away the previous day. The few remaining French in the Brandenburger’s path scattered rapidly, in some disarray. Two hundred prisoners were taken, and then followed a wild pursuit after a fleeing enemy. Within less than 25 minutes, advanced detachments from the 2nd Battalion of the 24th had reached the objective, having progressed over three-quarters of a mile. It was just about a record for that war.

On the extreme left of the 2nd Battalion was a section of Pioneers, commanded by a Sergeant Kunze. Kunze at 24 was a regular soldier of Thuringian peasant stock; from his photograph one gets the impression of heavy hands and limited intelligence; from his subsequent action, one gets an impression of complete fearlessness, but perhaps of that variety of boldness that often reflects lack of imagination. Men like Kunze were the backbone of any German Army; they would go forwards in execution of what they held to be their orders, unquestioningly and unthinkingly, until at last a bullet dropped them. In the usual practice of the German Army, Kunze’s section had been detailed to accompany the first wave of storm troops, to clear any wire or other obstacle that might hold them up. Aided by the land contours, it was on the objective well to the fore. Kunze himself had already had an eventful afternoon. In a captured machine-gun post he had stopped and given first-aid to a wounded French NCO, but the ungrateful gunner had somehow regained his weapon and reopened fire. Kunze hastily returned and dispatched the man with little compunction. At another enemy position, a few minutes later, Kunze saw a Frenchman raise his rifle, but he shot first. When at last he reached the objective his blood was thoroughly up; after the day’s brief action he was, in that favourite but quite untranslateable German Army expression,

unternehmungslustig.

As he paused to recover his breath, he saw the great dome of Douaumont looming ahead, incredibly close to him, terrifying but at the same time irresistibly enticing. French machine guns were chattering away busily to the right, but the Fort seemed silent. Kunze now reconsidered the orders he had received that morning; to eliminate all obstacles in front of the advancing infantry. And here, just in front of him, was the biggest obstacle of all! Ignoring in the excitement of the moment the other order — not to go beyond the prescribed objective — and with little thought as to what he would do when (or if) he got there, he set off in the direction of the Fort. His section followed obediently. Ten men against the world’s most powerful fortress! It seemed an act of the most grotesque lunacy.

Within a matter of minutes Kunze and his section reached the wire on the Fort glacis. Encouragingly enough, nobody had fired at them, but Kunze had noticed the 155 in the Fort shooting over their heads at some distant target. He also noticed troops on the right flank of the 24th being given a bad time by a French machine gun cunningly placed aloft the church spire in the village of Douaumont. Much of the heavy barbed wire had been torn up by the German bombardment, and — with the aid of their pioneer wire-cutters — the section soon made a way through the two entanglements. They reached the spiked railings some 50 yards east of the northern apex of the fort. It was now shortly after 3.30. There was absolutely no way of getting through or over the obstacle. Kunze now followed the railings, moving leftwards; his choice apparently dictated by the machine gun over to his right. He turned the north-east corner and there, just round it, to his delight was a gap about four feet wide that a shell had blasted in the railing. While contemplating how to get down into the 24-foot abyss of the moat, Divine Providence made up Kunze’s mind for him, in the shape of a near-miss that wafted him over the edge. Temporarily stunned, but otherwise unhurt, Kunze now urged the rest of his section to join him. A corporal, convinced by now that the section leader was out of his mind, announced that he was pulling back, but — possibly persuaded by their own heavy shells which were still falling thickly on the exposed superstructure of the fort — the remainder lowered each other down to where Kunze was standing.