The President's Vampire: Strange-But-True Tales of the United States of America (4 page)

Read The President's Vampire: Strange-But-True Tales of the United States of America Online

Authors: Robert Schneck

The Suttons and Taylor eventually had enough; they got into two cars and drove the seven miles to Hopkinsville, bringing back state, local, and military police from Fort Campbell who investigated the scene. Screens were shot out, empty shell-casings littered the floor, and what was described as a luminous patch was seen in the grass. This quickly disappeared. The police left sometime after 2 AM and the goblins (who would not take a hint) came back to look through the windows until shortly before sunrise when they vanished for good.

Thirty-one years earlier and a continent away, less ethereal creatures attacked a group of miners in the woods of the Pacific Northwest. In this case, however, the creatures seemed intent on homicide.

Gorilla Warfare

Fred Beck spent years prospecting for gold in the Mt. St. Helens, Lewis River area of southwest Washington. He worked with other men, who have been identified as Marion Smith, Gabe Lefever, and John Peterson. They occasionally saw large unexplained tracks and, in 1924, heard whistling and thumping noises in the evenings. One day in mid-July, Beck and Smith were going for water when they saw a dark hairy figure standing around seven feet tall. They fired on it and Marion Smith was certain he had put five shots into “that fools’ head” but it ran down a ridge and escaped. (30)

Around midnight, the creatures counter-attacked. The men were asleep in their cabin when it was hit by a “tremendous thud” that woke them and knocked the chinking out of the pine log wall. They grabbed their rifles, looked through the spaces in the wall, and saw two or three “mountain devils” outside, though they could hear more of them walking around. Large stones were thrown at the cabin and some of them came down the chimney; this went on all night. The creatures climbed on to the roof and it “sounded like a bunch of horses were running around there.”(31) They tried breaking down the door, pushing the building over, and at one point a hairy hand reached through a space in the chinking hole and grabbed an axe. Smith turned the blade so it could not be pulled through the gap and shot at the thing. The men held their fire except when the sasquatches attacked, trying to communicate the idea that they were only defending themselves, but the assault continued until shortly before dawn.

The sun was well up before the defenders left the safety of the cabin. A creature was standing nearby and Beck shot it three times with a rifle, sending it tumbling down a canyon. They reached the road, got into their Ford, and escaped, abandoning the cabin along with several hundred dollars worth of mining equipment. The site was named Ape Canyon in recognition of the event and, in 1967, Beck published an account titled

I Fought the Apemen of Mount St. Helens, WA

. (The cabin burned down long ago, but the canyon survived the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980 and is now part of the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. An enormous lava tube called Ape Cave is nearby.)

Beck’s booklet gives the history of the siege, but he is more interested in the metaphysical aspects of the case. He described himself as clairvoyant and a psychic healer and believed the men he worked with were similarly gifted. They used these abilities to find gold (“The method we found our mine was psychic”) and believed they were in contact with spirit beings. Despite the sasquatches’ seemingly physical nature, along with the stone throwing, footprints, and axe grabbing, Beck felt “they cannot be natural beings with natural bodies.” His metaphysical approach is not easy to understand, but he seems to have believed they were primitive spirits that materialized in the physical world without being real living things. Consequently, they cannot be killed or captured, but it does not follow that they’re harmless.

“There was enough physical force present to kill more than the number of our party,” according to Beck. “If that fate had fallen on us in 1924, they probably would have found five wrangled bodies and a disheveled cabin, and strange large tracks around the area. Of course, there would have been an investigation, but a so called logical explanation would have been given.”(32)

Since the ape-men are psychical, rather than physical, manifestations, not everyone will encounter them. The miners were especially sensitive to spiritual vibrations and Beck felt that “persons who are psychic have a degree of involvement in a sighting and help trigger the phenomenon.”(33) Other writers have proposed similar theories, and, if they’re right, perhaps Ebenezer Babson was Gloucester’s “psychic trigger.”

Three Paranormal Sieges

Gloucester, Kelly, and Ape Canyon are normally considered three different kinds of paranormal phenomena. The raiders’ appearance near Salem during the witch mania has made it a footnote to what could have been an unrelated event. Billy Ray Taylor’s flying saucer sighting put Kelly/Hopkinsville in the UFO literature as an early and unusual example of a close encounter of the third kind, but what if Taylor hadn’t looked into the sky and seen something he couldn’t identify? How would it be classified? (Beck might argue that the sighting itself triggered the appearance of the goblins.) Ape Canyon is considered a classic of cryptozoology, the study of unknown or “hidden” animals, but as researcher John Green points out, “There is no other report of sasquatches engaging in any elaborate form of combined activity, let alone a concerted attack on a human habitation.”(34)

Each of these events is something of an anomaly even among anomalous events; not unique perhaps, but certainly untypical, and with some common elements. All three took place in the summer, in wooded areas, and each involved armed civilians taking refuge in buildings and defending themselves from an apparent threat by beings that did not seem wholly physical. The witnesses experienced terror, but there is no record of them suffering any injury, either directly or indirectly. In fact, the only physical contact mentioned in any of the episodes took place when one of the Kelly gargoyles touched Billy Ray Taylor’s head. Even in Ape Canyon, where the attackers’ intentions seemed murderous, they did no more actual harm than either the inquisitive goblins or musket-toting phantoms. Fred Beck makes the point that “Some accounts state I was hit in the head by a rock and knocked unconscious. This is not true.”

It does not follow, however, that these incidents weren’t traumatic. The miners never returned to the cabin, the Suttons moved a short time later, and Babson’s mother apparently left the farm. In each story the beings were hit by gunfire without leaving bloodstains, none of them voiced pain, surprise, or anger, or had their movements impeded by injury. Beck claims that the last creature he shot may have been killed, but it fell into a canyon so there’s no way to be sure; the goblins and raiders went down too, but didn’t stay down.

The sieges almost seem like theatrical productions. They are real and not real at the same time, with the audience experiencing genuine terror because it doesn’t know it’s witnessing a strange and pointless play.

It has been over 300 years since the phantoms appeared in Gloucester. Little remains from that period and landmarks like the Babson farm and the garrison vanished long ago.

I wondered if the musket ball found in the hemlock tree, the one piece of physical evidence preserved at the time, was still around. None of the museums or historical societies in Cape Ann knows where it is, but that doesn’t mean it’s gone forever. The bullet may be in a trunk in the attic of some Babson descendant, waiting to be found, wrapped, perhaps, in the pages of its own history like Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter.

While looking for the phantom’s fugitive musket ball I was not surprised to learn that another relic has survived the centuries. Mary H. Sibbalds, president of The Sandy Bay Historical Society and Museum, wrote to me saying: “I honestly believe that if anyone in the Babson family possessed what they believed to be the famous bullet, they would have given it to the SBHS. We do have the knife with which Ebenezer supposedly killed the bear of Bearskin Neck!“(35)

2

BRIBING THE DEAD

Morristown, New Jersey, 1788

The story of a fake sorcerer who got rich

by convincing imitation ghosts to hand over a non-existent fortune.

One night, on the outskirts of Morristown, New Jersey, forty men assembled in a lonely field and began to march. A few years earlier General Washington’s Continental Army may have marched through this same field but that night they were mainly farmers who were engaged in raising something a lot more interesting than either rebellion or buckwheat. Candles threw faint trembling shadows onto the surrounding trees and illuminated the sorcerer who presided over the ritual. He stood beneath an awning, directing the procession as it followed occult pattern of circles, squares and triangles that were laid out on the ground. Most of the men were tired and the whole company was more or less drunk, but neither liquor nor fatigue could make them forget the doom that awaited any who stepped outside the protective boundaries of the diagram. Perhaps they thought a careless foot had gone astray when a column of flame burst from the earth, exploding in their ears and dazzling their eyes. Men, trees, and diagrams were briefly visible in the flash, along with

something

that stood outside the safety of the magic circle, something that was not of this world.

Silence and darkness followed the eruption and the hush continued until a low groaning was heard coming from the direction of the trees. A tortured howl filled the November night and was quickly joined by a chorus of shrieks that lifted the hairs on the assembly’s necks and, no doubt, left many of the quietly terrified men wondering if there weren’t easier ways of getting rich.

The line separating sorcerers from confidence men is not always clear. Among the Tungus people of Siberia, for example, shamans use sleight of hand in their healing rituals to make it appear that an illness has been actually, physically extracted from the patient’s body in the form of a stone. This is a deliberate deception carried out to convince sick people that they are cured and help bring about their recovery. What happened in Morristown is not an example of that sort of thing. The “sorcerer” in this case was a Yankee schoolmaster named Ransford Rogers and the sole purpose of his deception was to squeeze money out of the participants until they squeaked.

Before taking up necromancy, Rogers was a teacher in the town of Smith’s Clove, New York. There he became acquainted with two men who had traveled from New Jersey in search of a person who could help them to find buried treasure. They believed it was hidden in a mountain twenty miles to the west of their homes in Morristown, but that any attempts to remove it were doomed to fail “for want of a person whose knowledge descended into the bowels of the earth, and who could reveal the secret things of darkness.”(1)

The Set-Up

Schooley’s Mountain, which was then known as “Schooler’s Mountain, is “a veritable range of highlands” in Morris County.(2) According to various rumors, gossip, and legends, riches began accumulating there during the Revolution when Tories and Tory-sympathizers hid their wealth on the mountain. They were followed by patriots, who buried their money, but died fighting the King’s armies and were unable to dig it up. Pirates were said to have contributed to the hoard, though it’s hard to imagine a crew of buccaneers humping their doubloons so far inland. If they did, it might explain the six men said to have been murdered where “X” marked the spot; pirates had a reputation for killing members of the burying detail so their ghosts would haunt the place and drive away prospective thieves. It was these ghoulish overseers that concerned the treasure hunters, for, even if they found their prize, they couldn’t carry it away without subduing, placating, or otherwise avoiding these spirits.

Rogers soon convinced the men that he was adept in the mystic arts and had powers equal to the task. The schoolmaster made an excellent impression for he was “very affable in his manners and had a genius adequate to prepossess people in his favor. He was an illiterate person but was very ambitious to maintain an appearance of possessing profound knowledge.“(3) (Presumably, Rogers was literate enough to teach school.) The treasure hunters invited him to settle in Morristown where they would find him a position, and Rogers accepted. It’s been suggested that his main interest was a teaching job (with, perhaps, a sideline in swindling) but whatever his motives, he would soon display a masterful hand at the art of flim-flam. In August 1788, Rogers had relocated and was teaching in a schoolhouse three miles west of Morristown. In his trunks, among the hornbooks, birches, tri-cornered hats and buckled shoes, there may have been a copy of Giambattista della Porta’s

Natural Magick

and a supply of chemicals, for Rogers knew something about alchemy as well as conjuring.

Good Enough

The sorcerer was a popular schoolmaster, but soon requested a leave of absence to visit his family in Connecticut. This was granted and when Rogers returned he brought another schoolmaster named Goodenough. Goodenough was hired by the school and would secretly assist Rogers during the magical treasure hunt. The wizard’s sponsors were anxious to begin work and he wasn’t going to disappoint them, or, more accurately, he was going to disappoint them, but not completely. They would get a good show for their money. Rogers would eventually mount displays so elaborate that more help was needed, but at this point Goodenough was, well, good enough to provide the simple spook effects needed at the first gathering of what would come to be called the Fire Club. (It would also be called the Spirit Batch, the Company, and very likely other names that are out of place in a genteel history like this.)

In September, the first eight members of the club met in a secluded house owned by Mr. Lum, a local farmer. He lived in an area so remote it was nicknamed “Solitude,” but even in this isolated spot Rogers had the men seal the doors and windows. What they were about to do required more than ordinary privacy, and when Rogers felt sure that no one could see in (or out), he took the floor. The spirits, he announced with appropriate solemnity, had reached out to him. Post-mortem informants had confirmed the presence of immense treasures in Schooley’s Mountain and that obtaining them was possible. The process would be complicated and time consuming because Rogers needed to study the spirits and discover what might induce them to resign their guardianship. He “proposed to serve as a medium between the seekers and the guardians of the treasure,”(4) but would not expect the gentlemen assembled to simply accept what he said on faith; to prove that he was a genuine wizard, he would summon up spirits in the company’s presence and converse with them at a future meeting. In the meantime, it was essential for everyone involved in the project to behave with perfect uprightness. Immorality of any kind would offend the spirits and could cause the whole undertaking to collapse.

If Rogers’ words weren’t impressive enough, their effect was enhanced by mysterious rappings on the walls and ceiling that punctuated his speech, and a disembodied voice that said, “Push forward.” Everyone agreed that the first meeting was a great success.

The schoolmaster was serving up an intoxicating mixture of greed, piety, sorcery and secrecy that quickly attracted new members. They were all male; women and wives weren’t invited to join, and forty men were soon attending regular meetings where Rogers described the progress of his negotiations with the spirits, followed by refreshments.

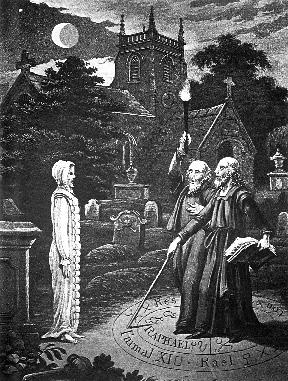

The Elizabethan sorcerer Edward Kelley and an accomplice at work in a churchyard. They are probably using spells and incantations to make the spirit reveal the location of a hidden treasure. (Fortean Picture Library)

Firewater

Americans of the period weren’t afraid to bend an elbow. “In matters of drunkenness there was no difference observable between the classes or colonies and not seldom as much liquor was consumed in the ordination of a New England minister as at a barbecue in the South, while the velvet-coated dandy slipped under the table no more readily than the leather-jerkined plowman.”(5) Rogers’ seances were no less festive and his followers were encouraged to enjoy a good soak that dulled their critical faculties and “raised their ideas,”(6) or, as female impersonators are fond of saying, “The more you drink, the better we look.” A colonist’s choice of tipple was largely determined by geography and for New Jerseyans the drink was applejack. This is a brandy distilled from hard cider that the locals called “Jersey Lightning.” They drank it straight or as Scotchem, a mixture of applejack and boiling water with a dash of mustard.(7) Then came prayers and demonstrations of occult skill.

“At one of the early meetings Rogers gathered the members of the cult into a field near the meeting house and flung the chemicals into the sky before the eyes of the wondering group. They exploded on the night air in a variety of appearances, downright extraordinary if nothing short of mysterious. The design of the hoaxer to play upon the active imaginations of his audience did not miscarry. These and subterranean explosives, previously planted and timed to discharge during the night to enhance their dismal effect and to engender timidity in the souls of the elect, were pronounced by the awed group to be, without equivocation, of supernatural origin and character.”(8)

Magician-scientist Larry White doubts that Rogers’ feats could have been performed quite this way. He writes: “There is nothing I can think of that one can simply toss into the air to ‘exhibit appearances so extraordinary…’ IF such stuff were used in 1788 you can be certain stage magicians would be using it today. We ain’t! AND, because many chemicals we know and use today were unknown in 1788 it is almost inconceivable to me that…Rogers…would have access to any chemicals that could accomplish this. I put it down to ‘legend.’

“Burying a substance that later exploded MIGHT be possible. If I buried a piece of dynamite (which I do not think had been invented in 1788) with a VERY slow burning fuse it MIGHT explode much later. But 1788 is pushing things a bit, so you would have to consider GUNPOWDER which was known then. Possibly a ‘firecracker’ kind of shell made with gunpowder and a slow fuse… but tricky to do.

“Also consider this possibility…a campfire is lit…Rogers walks to it and tosses some ‘elements’ into it which flash and burn. Loose gunpowder? The statement that ‘he tossed it in the air’ may now, centuries later, ignore the fact that there WAS a fire present.“(9)

Giambattista Della Porta’s book(10) includes a recipe that suggests Mr. White is right. Chapter XI of

The Twelveth Book of Natural Magick

is headed “Fire Compositions for festival days” and it includes a method for casting “flame a great way.”

“Do thus: Beat Colophonia, Frankincense, or Amber finely. And hold them in the palm of your hand, and put a lighted candle between your fingers. And as you throw the powder into the air, let it pass through the flame of the candle. For the same will fly up high.”

The book also contains instructions for making land mines.

In addition, Mr. Lum and other members of the club saw a spectral figure gliding through the air. Like all the wonders, this was readily accepted by the group, which included a Revolutionary War colonel, an “eminent jurist,” two justices of the peace, and two physicians.(11) (Historians have suggested that the floating ghost was one of the conspirators walking on stilts.)

Founding Phantoms

The late eighteenth-century is often seen as a clear-minded interval between the witch-manias of the seventeenth century and the rise of Spiritualism in the nineteenth. The standard view is that “Apart from the doings at Salem, colonial America has little to offer in the way of occult history,”(12) and one gets the impression that the taverns were full of rationalist, humanitarian, and scientifically inclined patriots discussing electricity and inalienable rights over tankards of ale. Superstition, however, exerted a powerful influence on the minds of many colonial Americans. The widespread interest in alchemy, astrology, ghosts, spells, magical cures, and dowsing suggests that ordinary citizens may have been less like the Founding Fathers and more like their grandfathers, who threw witches into ponds to see if they’d float.(13)

In 1730, for example, a man and a woman in Mt. Holly were accused of “making their Neighbors’ Sheep dance- in an uncommon Manner, and with causing Hogs to speak and sing Psalms, &c, to the great Terror and Amazement of the King’s good and peaceable Subjects of this Province.”(14) The accused were bound and dropped into the water, a test known as “swimming.” It worked because water “rejected” the guilty and would not let them sink, while the innocent went down. (The Mt. Holly couple agreed to undergo the ordeal on condition that their accusers also did; the results were inconclusive.)