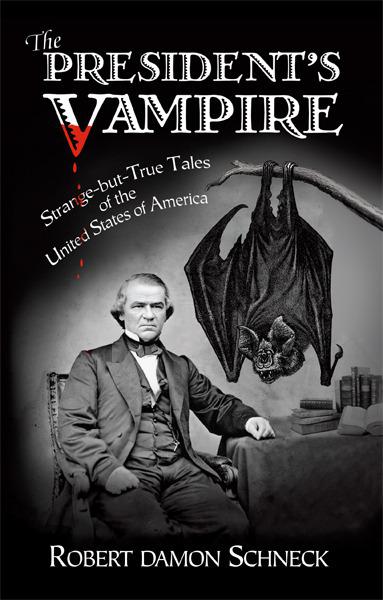

The President's Vampire: Strange-But-True Tales of the United States of America

Read The President's Vampire: Strange-But-True Tales of the United States of America Online

Authors: Robert Schneck

| The President's Vampire: Strange-But-True Tales of the United States of America |

| Schneck, Robert |

| Anomalist Books (2010) |

SUMMARY: THE PRESIDENT'S VAMPIRE is proof positive that an inordinate number of very strange things happen from sea to shining sea in the place known as the United States of America. It contains scrupulously documented accounts of ghosts, monsters, murderers, and hoaxes so improbable they will fascinate believers, skeptics, and anyone interested in the more obscure corners of American history and culture. "Robert Schneck is one of the best of a new breed of investigators into the relatively unknown byways of our cultural history. Because he is thoroughly familiar with his subject, writes with deceptive ease and a clarity that both amuses and educates, and because he never forgets that at the heart of even the strangest or most frightening of mysteries there are real human beings with a story to tell, I recommend him as a trusted guide." - Bob Rickard, Fortean Times Robert Damon Schneck is a freelance writer and contributor to Fortean Times, Fate, and other magazines. Friends describe him as a "loveable, nocturnal, monomaniac."

THE PRESIDENT’S VAMPIRE

Strange-but-True Tales of the United States

ROBERT DAMON SCHNECK

A

nomalist

B

ooks

San Antonio

•

New York

An

Original

Publication of ANOMALIST BOOKS

The President’s Vampire

Copyright © 2005 by Robert Damon Schneck

ISBN: 1-93366564-5

An earlier version of the chapter entitled “The President’s Vampire” appeared in

Fortean Times

, November 2004. “The God Machine” was first published in

Fortean Times

, June 2002, and a portion of “The Bridge to Body Island” appeared in

Swank

, February 2002. “After 18 Years, Missing Teens’ Bodies Found in Submerged Van,” March 3, 1997, is reprinted with permission of The Associated Press.

Book design by Ansen Seale

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For information, go to

anomalistbooks.com

or write to:

Anomalist Books

5150 Broadway #108

San Antonio, TX 78209

This book is dedicated with much love,

to my parents,

Beverly and Arnold.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 The Devil’s Militia

2 Bribing the Dead

3 The God Machine

4 The President’s Vampire

5 One Little Indian

6 A Horror in the Heights

7 The Lost Boys

8 The Bridge to Body Island

Epilogue

Notes

Appendix I: Entries in the logbook of the bark,

Atlantis

Appendix II: James Brown’s letter to the President

Appendix III: How dangerous was James Brown?

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION

“Unbelievable but true events that are beyond scientific understanding, beyond rational explanation. They will whet your imagination’s appetite in the startling breathtaking pages of

IMPOSSIBLE –Yet It Happened

!” (1)

The bottom shelf of my bookcase is devoted to a single genre (or sub-genre) of literature known as the “strange-but–true.” I have about a dozen of them there including Frank Edwards’ seminal

Stranger than Science,

along with his rivals and imitators;

Strange Monsters and Madmen, Impossible -Yet It Happened! , “Things,” More “Things,” Ghosts Ghouls & Other Horrors, Vampires Werewolves & Ghouls, This Baffling World, No Earthly Explanation, Strange Encounters With Ghosts, Strange Guests, Strange Disappearances, Strange Unsolved Mysteries

and

Strangely Enough!

It’s not a pretty collection, and it wouldn’t look good under glass, but their shabbiness is a testament to being read. If I understood

The Velveteen Rabbit

correctly, it’s the most loved toys that are left in the worst shape and the same applies to books. Every dog-eared page, cracked spine and water-damaged cover is visible evidence of being carried around in book-bags with half-eaten peanut-butter sandwiches and read at the dinner table, in the bathtub, and discreetly during math class (I missed fractions completely.) As for quality, they’re mostly hackwork, with the contents lifted from back issues of

Fate

magazine and laid out in the pattern set by Frank Edwards: take dozens of bizarre and/or inexplicable stories, retell them in two or three pages and top it off with a lurid title.

Some are paranormal (“The Hep Poltergeist That Dug Rock and Roll,” “Tennessee’s Horrible Wart Monster,” “Cigar in the Sky”) but there are also unexplained disappearances, natural and historical mysteries, gruesome murders, peculiar ideas (like perpetual motion, the hollow Earth) and even unusual diseases (“The Boy Who Died of Old Age”). I loved them all, and they became part of the permanent furniture of my mind.

Not everyone shared my enthusiasm. Teachers, for example, were more interested in the principle exports of Bolivia than the nine basic categories of sea serpents, an attitude that baffled me then and still does today. Also, young readers would be well advised to avoid these subjects in their schoolwork; too many papers on vampire-killing techniques, headless ghosts, or living dinosaurs in the Congo, and you’ll be taken to an office where people with soothing voices show you inkblots. Many still consider a fascination with strange subjects to be a symptom of maladjustment, and even I am considered a bit eccentric, a perception reinforced by nocturnal lemur-like habits, numerous obsessions, and several phobias.

I Digress

Strange-but-true stories have been recorded since people began writing. Ancient literature is full of wonders, and chroniclers of the period did not see the fantastic as somehow separate from subjects like politics and war. For example, Herodotus, “The Father of History,” described races of monstrous men, swarms of winged snakes, “gold-guarding Griffins,” and countless other marvels. Medieval and renaissance tales are top-heavy with miracles, and the Revs. Increase and Cotton Mather continued the collecting of “Memorable Providences” in the New World. The 19th century turned out numberless pseudoscientific and spiritualist books, along with pamphlets describing local oddities and the “true histories” sold by sideshow performers, most of whom were apparently captured after a bloody struggle in the jungles of Borneo. Cartoonist Robert L. Ripley’s popular newspaper column, “Believe It or Not!” first appeared in 1918, but for many the modern era of strange-but-true writing began a year later with the publication of Charles Hoy Fort’s

The Book of the Damned

.

Fort (1874-1932) was a journalist and novelist from Albany, New York, who spent most of his time in libraries copying down the anomalies reported in newspapers, magazines, and scientific journals. He was not too discriminating about sources, but the sheer quantity of data are startling, and

The Book of the Damned

was followed by three more;

New Lands

(1923),

Lo!

(1931), and

Wild Talents

(1932). Fort was interested in producing something more than entertaining collections, however, and the “damned” he referred to were those things that had been excluded or ignored by science.

Mysterious phenomena suggest that laws of nature are not fully understood, but Fort took an extreme position, writing, “I conceive of nothing in religion, science or philosophy, that is more than the proper thing to wear, for a while.” In other words, everything is somewhat true, somewhat false, and always changing.

Fort was also a wag and offered waggish solutions for the mysteries he collected. How were the pyramids built? “I now have a theory that the Pyramids were built by poltergeist-girls,”(2) meaning by telekinesis. Astronomers see a dark object moving through space; it might be an asteroid but Fort suggests it could also be, “a vast, black, brooding vampire.”(3) He even had an elegant explanation for how werehyena-ism might work: ”…there is no man who is without the hyena-element in his composition, and that there is no hyena that is not at least rudimentarily human… it may be reasoned that, by no absolute transformation, but by a shift of emphasis, a man-hyena might turn into a hyena-man.”(4) In addition, Fort coined the word “teleportation” and invented a game called super-checkers.

His influence on me was indirect because the books contained sentences like “A barrier to rational thinking, in anything like a final sense, is continuity, because of which only fictitiously can anything be picked out of a nexus of all things phenomenal, to think about.” These came along often enough to be discouraging, and I drifted back to the cheap strange-but-true literature that historian T. Peter Park has described as “gee-whiz pop forteanism.”

"AN AMAZING BOOK OF FANTASTIC YET VERIFIED TRUE EVENTS..." (5)

Tracking Down the Strange

In time, the gee-whiz paperbacks gave way to more substantial reading and vanished beneath accumulating layers of books until they formed the trilobite stratum of my library. Works by Rupert T. Gould, Bernard Heuvelmans, and Ivan Sanderson succeeded them and strongly influenced my own approach to writing. I try to authenticate as much of the material as possible and discuss aspects of it in relationship to history, the paranormal, crime, folklore, science, or anything else that contributes to the making of a “large and fruitful disorder.” Failing that, I will settle for an interesting sprawl, but unlike Fort, anomalies are my way of discovering unfamiliar corners of reality, not evidence for overturning conventional views of it.

While looking into the history of Pedro the mummy, for instance, I expected to learn that the popular version was distorted, and possibly a hoax. There were elements of this, but research also turned up surprising aspects of folklore, science, and the things people did to survive during the Great Depression, including amateur prospecting, looting ancient sites, and carving pygmy heads out of turnips. With the discovery of a second mummy, however, Wyoming’s local oddity seems poised to go even further, jumping from the pages of

Stranger than Science

to the science textbooks.

Solid physical evidence is almost unknown in cases of paranormal phenomena—a void that is normally filled by speculation. Should someone read

The President’s Vampire

in 2105, they will probably regard my faith in the rickety findings of parapsychology with the same mixture of amusement and condescension we feel for the writer of 1905 who explained the paranormal in terms of Spiritualism and who, in turn, felt the same way about the theories based on witchcraft and demons that were current in 1804. History shows that interpretations of the paranormal fall in and out of favor, while the paranormal itself continues to flap along being whatever it is and cocking a snoot at those that would explain or control it.

Since the strange-but-true is essentially a collection of old stories, an historical approach seems more appropriate than a scientific one. For the researcher, this means digging through libraries and archives, collecting accounts, comparing them to documented facts, and whenever possible, tracking down primary sources. Sometimes these can’t be found, but the research gods are generous and reward the diligent in other ways. Books open to the right page, strangers write with information, and wonderful stories drop out of the sky like fish and frogs. While piecing together the history of the Phantom of O’Donnell Heights, for example, I found what sounded like an encounter between a Mad Gasser and a world famous opera singer.

Bulgarian-born soprano Ljuba Welitsch was the star of the Vienna State Opera and had little in common with the twitchy housewives of Mattoon, Illinois. However, in Vienna, on the morning of July 22, 1951, the maid knocked on Madame Welitsch’s bedroom door and got no response. Entering from the balcony, she discovered the room filled with chemical fumes coming from a rug by the bed. It seemed to be saturated with chloroform.

Welitsch was eventually roused and the police summoned, but before they arrived, the rug was washed and “a rare Australian bird, gift… from a director of the New York Metropolitan Opera, was dead in the room where the rug had been hung to dry.”(6) Police took the rug away for analysis.

The singer said that an intruder must have sneaked into her room, but it was only accessible from the balcony used by the maid and this was thirty feet above the ground. Welitsch had nothing to add except regret for the loss of her “poor little bird.”

Was there a mad anesthetist loose in Austria? Had a crime been attempted? Were the singer and her maid concealing something? I have no idea, but the combination of phantom intruders, sopranos, chloroform, and Mitteleuropan policemen puzzling over the remains of a dead bird suggest that something more interesting than waltzing was going on in Vienna that summer.

This is catnip to me and it’s why I love studying the strange. Once you start looking, you never know what you’ll find. Or what will find you.