The Panda’s Thumb (13 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Teilhard's slip occurs in his description of the second Piltdown find. Teilhard writes: “He just brought me to the site of Locality 2 and explained me (sic) that he had found the isolated molar and the small pieces of skull in the heaps of rubble and pebbles raked at the surface of the field.” Now we know (see Weiner, p. 142) that Dawson did take Teilhard to the second site for a prospecting trip in 1913. He also took Smith Woodward there in 1914. But neither visit led to any discovery; no fossils were found at the second site until 1915. Dawson wrote to Smith Woodward on January 20, 1915 to announce the discovery of two cranial fragments. In July 1915, he wrote again with good news about the discovery of a molar tooth. Smith Woodward assumed (and stated in print) that Dawson had unearthed the specimens in 1915 (see Weiner, p. 144). Dawson became seriously ill later in 1915 and died the next year. Smith Woodward never obtained more precise information from him about the second find. Now, the damning point: Teilhard states explicitly, in the letter quoted above, that Dawson told him about both the tooth and the skull fragments of the second site. But Claude Cuénot, Teilhard's biographer, states that Teilhard was called up for service in December, 1914; and we know that he was at the front on January 22, 1915 (pp. 22â23). But if Dawson did not “officially” discover the molar until July, 1915, how could Teilhard have known about it

unless he was involved in the hoax

. I regard it as unlikely that Dawson would show the material to an innocent Teilhard in 1913 and then withold it from Smith Woodward for two years (especially after taking Smith Woodward to the second site for two days of prospecting in 1914). Teilhard and Smith Woodward were friends and might have compared notes at any time; such an inconsistency on Dawson's part could have blown his cover entirely.

Second, Teilhard states in his letter to Oakley that he did not meet Dawson until 1911: “I knew Dawson very well, since I worked with him and Sir Arthur three or four times at Piltdown (after a chance meeting in a quarry near Hastings in 1911).” Yet it is certain that Teilhard met Dawson during the spring or summer of 1909 (see Weiner, p. 90). Dawson introduced Teilhard to Smith Woodward, and Teilhard submitted some fossils he had found, including a rare tooth of an early mammal, to Smith Woodward late in 1909. When Smith Woodward described this material before the Geological Society of London in 1911, Dawson, in the discussion following Smith Woodward's talk, paid tribute to the “patient and skilled assistance” given to him by Teilhard and another priest since 1909. I don't regard this as a damning point. A first meeting in 1911 would still be early enough for complicity (Dawson “found” his first piece of the Piltdown skull in the autumn of 1911, although he states that a workman had given him a fragment “some years” earlier), and I would never hold a mistake of two years against a man who tried to remember the event forty years later. Still, a later (and incorrect) date, right upon the heels of Dawson's find, certainly averts suspicion.

Moving away from the fascination of whodunit to the theme of my original essay (why did anyone ever believe it in the first place), another colleague sent me an interesting article from

Nature

(the leading scientific periodical in England), November 13, 1913, from the midst of the initial discussions. In it, David Waterston of King's College, University of London, correctly (and definitely) stated that the skull was human, the jaw an ape's. He concludes: “It seems to me to be as inconsequent to refer the mandible and the cranium to the same individual as it would be to articulate a chimpanzee foot with the bones of an essentially human thigh and leg.” The correct explanation had been available from the start, but hope, desire, and prejudice prevented its acceptance.

IN MY PREVIOUS

book,

Ever Since Darwin

, I began an essay on human evolution with these words:

New and significant prehuman fossils have been unearthed with such unrelenting frequency in recent years that the fate of any lecture notes can only be described with the watchword of a fundamentally irrational economyâplanned obsolescence. Each year, when the topic comes up in my courses, I simply open my old folder and dump the contents into the nearest circular file. And here we go again.

And I'm mighty glad I wrote them, because I now want to invoke that passage to recant an argument made later in the same article.

In that essay I reported Mary Leakey's discovery (at Laetoli, thirty miles south of Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania) of the oldest known hominid fossilsâteeth and jaws 3.35 to 3.75 million years old. Mary Leakey suggested (and so far as I know, still believes) that these remains should be classified in our genus,

Homo

. I therefore argued that the conventional evolutionary sequence leading from small-brained but fully erect

Australopithecus

to larger-brained

Homo

might have to be reassessed, and that the australopithecines might represent a side branch of the human evolutionary tree.

Early in 1979, newspapers blazed with reports of a new speciesâmore ancient in time and more primitive in appearance than any other hominid fossil

âAustralopithecus afarensis

, named by Don Johanson and Tim White. Could any two claims possibly be more differentâMary Leakey's argument that the oldest hominids belong to our own genus,

Homo

, and Johanson and White's decision to name a new species because the oldest hominids possess a set of apelike features shared by no other fossil hominid. Johanson and White must have discovered some new and fundamentally different bones. Not at all. Leakey and Johanson and white are arguing about the same bones. We are witnessing, debate about the interpretation of specimens, not a new discovery.

Johanson worked in the Afar region of Ethiopia from 1972 to 1977 and unearthed an outstanding series of hominid remains. The Afar specimens are 2.9 to 3.3 million years old. Premier among them is the skeleton of an australopithecine named Lucy. She is nearly 40 percent completeâmuch more than we have ever possessed for any individual from these early days of our history. (Most hominid fossils, even though they serve as a basis for endless speculation and elaborate storytelling, are fragments of jaws and scraps of skulls.)

Johanson and White argue that the Afar specimens and Mary Leakey's Laetoli fossils are identical in form and belong to the same species. They also point out that the Afar and Laetoli bones and teeth represent everything we know about hominids exceeding 2.5 million years in ageâall the other African specimens are younger. Finally, they claim that the teeth and skull pieces of these old remains share a set of features absent in later fossils and reminiscent of apes. Thus, they assign the Laetoli and Afar remains to a new species,

A. afarensis

.

The debate is just beginning to warm up, but three opinions have already been vented. Some anthropologists, pointing to different features, regard the Afar and Laetoli specimens as members of our own genus,

Homo

. Others accept Johanson and White's conclusion that these older fossils are closer to the later south and east African

Australopithecus

than to

Homo

. But they deny a difference sufficient to warrant a new species and prefer to include the Afar and Laetoli fossils within the species

A. africanus

, originally named for South African specimens in the 1920s. Still others agree with Johanson and White that the Afar and Laetoli fossils deserve a new name.

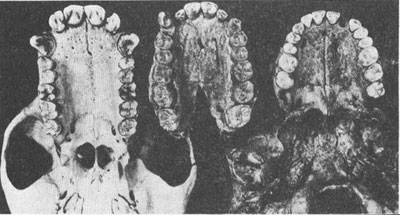

The palate of

Australopithecus afarensis

(center, compared with that of a modern chimpanzee (left) and a human (right).

COURTESY OF

T

IM

W

HITE AND THE

C

LEVELAND

M

USEUM OF

N

ATURAL

H

ISTORY

As a rank anatomical amateur, my opinion is worth next to nothing. Yet I must say that if a picture is worth all the words of this essay (or only half of them if you follow the traditional equation of 1 for 1,000), the palate of the Afar hominid certainly says “ape” to me. (I must also confess that the designation of

A. afarensis

supports several of my favorite prejudices. Johanson and White emphasize that the Afar and Laetoli specimens span a million years but are virtually identical. I believe that most species do not alter much during the lengthy period of their success and that most evolutionary change accumulates during very rapid events of splitting from ancestral stocksâsee essays 17 and 18. Moreover, since I depict human evolution as a bush rather than a ladder, the more species the merrier. Johanson and White do, however, accept far more gradualism than I would advocate for later human evolution.)

Amidst all this argument about skulls, teeth, and taxonomic placement, another and far more interesting feature of the Afar remains has not been disputed. Lucy's pelvis and leg bones clearly show that

A. afarensis

walked as erect as you or I. This fact has been prominently reported by the press, but in a very misleading way. The newspapers have conveyed, almost unanimously, the idea that previous orthodoxy had viewed the evolution of larger brains and upright postures as a gradual transition in tandem, perhaps with brains leading the wayâfrom pea-brained quadrupeds to stooping half brains to fully erect, big-brained

Homo

. The

New York Times

writes (January 1979): “The evolution of bipedalism was thought to have been a gradual process involving intermediate forerunners of modern human beings that were stooped, shuffle-gaited âape-men,' creatures more intelligent than apes but not as intelligent as modern human beings.” Absolutely false, at least for the past fifty years of our knowledge.

We have known since australopithecines were discovered in the 1920s that these hominids had relatively small brains and fully erect posture. (

A. africanus

has a brain about one-third the volume of ours and a completely upright gait. A correction for its small body size does not remove the large discrepancy between its brain and ours.) This “anomaly” of small brain and upright posture has been a major issue in the literature for decades and wins a prominent place in all important texts.

Thus, the designation of

A. afarensis

does not establish the historical primacy of upright posture over large brains. But it does, in conjunction with two other ideas, suggest something very novel and exciting, something curiously missing from the press reports or buried amidst misinformation about the primacy of upright posture.

A. afarensis

is important because it teaches us that perfected upright gait had already been achieved nearly four million years ago. Lucy's pelvic structure indicates bipedal posture for the Afar remains, while the remarkable footprints just discovered at Laetoli provide even more direct evidence. The later south and east African australopithecines do not extend back much further than two and a half million years. We have thus added nearly one and a half million years to the history of fully upright posture.

To explain why this addition is so important, I must break the narrative and move to the opposite end of biologyâfrom fossils of whole animals to molecules. During the past fifteen years, students of molecular evolution have accumulated a storehouse of data on the amino acid sequences of similar enzymes and proteins in a wide variety of organisms. This information has generated a surprising result. If we take pairs of species with securely dated times of divergence from a common ancestor in the fossil record, we find that the number of amino acid differences correlates remarkably well with time since the splitâthe longer that two lineages have been separate, the more the molecular difference. This regularity has led to the establishment of a molecular clock to predict times of divergence for pairs of species without good fossil evidence of ancestry. To be sure, the clock does not beat with the regularity of an expensive watchâit has been called a “sloppy clock” by one of its leading supportersâbut it has rarely gone completely haywire.

Darwinians were generally surprised by the clock's regularity because natural selection should work at markedly varying rates in different lineages at different times: very rapidly in complex forms adapting to rapidly changing environments, very slowly in stable, well-adapted populations. If natural selection is the primary cause of evolution in populations, then we should not expect a good correlation between genetic change and time unless rates of selection remain fairly constantâas they should not by the argument stated above. Darwinians have escaped this anomaly by arguing that irregularities in the rate of selection smooth out over long periods of time. Selection might be intense for a few generations and virtually absent for a time thereafter, but the net change averaged over long periods could still be regular. But Darwinians have also been forced to face the possibility that regularity of the molecular clock reflects an evolutionary process not mediated by natural selection, the random fixation of neutral mutations. (I must defer this “hot” topic to another time and more space.)

In any case, the measurement of amino acid differences between humans and living African great apes (gorillas and chimpanzees) led to the most surprising result of all. We are virtually identical for genes that have been studied, despite our pronounced morphological divergence. The average difference in amino acid sequences between humans and African apes is less than one percent (0.8 percent to be precise)âcorresponding to a mere five million years since divergence from a common ancestor on the molecular clock. Allowing for the slop, Allan Wilson and Vincent Sarich, the Berkeley scientists who uncovered this anomaly, will accept six million years, but not much more. In short, if the clock is valid,

A. afarensis

is pushing very hard at the theoretical limit of hominid ancestry.

Until recently, anthropologists tended to dismiss the clock, arguing that hominids provided a genuine exception to an admitted rule. They based their skepticism about the molecular clock upon an animal called

Ramapithecus

, an African and Asian fossil known mainly from jaw fragments and ranging back to fourteen million years in age. Many anthropologists claimed that

Ramapithecus

could be placed on our side of the ape-human splitâthat, in other words, the divergence between hominids and apes occurred more than fourteen million years ago. But this view, based on a series of technical arguments about teeth and their proportions, has been weakening of late. Some of the strongest supporters of

Ramapithecus

as a hominid are now prepared to reassess it as an ape or as a creature near to the common ancestry of ape and human but still before the actual split. The molecular clock has been right too often to cast it aside for some tentative arguments about fragments of jaws. (I now expect to lose a $10 bet I made with Allan Wilson a few years back. He generously gave me seven million years as a maximum for the oldest ape-human common ancestor, but I held out for more. And while I'm not shelling out yet, I don't really expect to collect.

*

)

We may now put together three points to suggest a major reorientation in views about human evolution: the age and upright posture of

A. afarensis

, the ape-human split on the molecular clock, and the dethroning of

Ramapithecus

as a hominid.

We have never been able to get away from a brain-centered view of human evolution, although it has never represented more than a powerful cultural prejudice imposed upon nature. Early evolutionists argued that enlargement of the brain must have preceded any major alteration of our bodily frame. (See views of G. E. Smith in essay 10. Smith based his pro-Piltdown conviction upon an almost fanatical belief in cerebral primacy.) But

A. africanus

, upright and small brained, ended that conceit in the 1920s, as predicted by a number of astute evolutionists and philosophers, from Ernst Haeckel to Friedrich Engels. Nevertheless, “cerebral primacy,” as I like to call it, still held on in altered form. Evolutionists granted the historical primacy of upright posture but conjectured that it arose at a leisurely pace and that the real discontinuityâthe leap that made us fully humanâoccurred much later when, in an unprecedented burst of evolutionary speed, our brains tripled in size within a million years or so.

Consider the following, written ten years ago by a leading expert: “The great leap in cephalization of genus

Homo

took place within the past two million years, after some ten million years of preparatory evolution toward bipedalism, the tool-using hand, etc.” Arthur Koestler has carried this view of a cerebral leap toward humanity to an unexcelled height of invalid speculation in his latest book,

Janus

. Our brain grew so fast, he argues, that the outer cerebral cortex, seat of smarts and rationality, lost control over emotive, animal centers deep within our brains. This primitive bestiality surfaces in war, murder, and other forms of mayhem.