The Panda’s Thumb (11 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

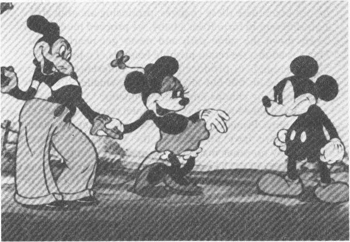

Humans feel affection for animals with juvenile features: large eyes, bulging craniums, retreating chins (left column). Small-eyed, long-snouted animals (right column) do not elicit the same response. From

Studies in Animal and Human Behavior

, vol. II, by Konrad Lorenz, 1971. Methuen & Co. Ltd.

We cannot help regarding a camel as aloof and unfriendly because it mimics, quite unwittingly and for other reasons, the “gesture of haughty rejection” common to so many human cultures. In this gesture, we raise our heads, placing our nose above our eyes. We then half-close our eyes and blow out through our noseâthe “harumph” of the stereotyped upperclass Englishman or his well-trained servant. “All this,” Lorenz argues quite cogently, “symbolizes resistance against all sensory modalities emanating from the disdained counterpart.” But the poor camel cannot help carrying its nose above its elongate eyes, with mouth drawn down. As Lorenz reminds us, if you wish to know whether a camel will eat out of your hand or spit, look at its ears, not the rest of its face.

In his important book

Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

, published in 1872, Charles Darwin traced the evolutionary basis of many common gestures to originally adaptive actions in animals later internalized as symbols in humans. Thus, he argued for evolutionary continuity of emotion, not only of form. We snarl and raise our upper lip in fierce angerâto expose our nonexistent fighting canine tooth. Our gesture of disgust repeats the facial actions associated with the highly adaptive act of vomiting in necessary circumstances. Darwin concluded, much to the distress of many Victorian contemporaries: “With mankind some expressions, such as the bristling of the hair under the influence of extreme terror, or the uncovering of the teeth under that of furious rage, can hardly be understood, except on the belief that man once existed in a much lower and animal-like condition.”

In any case, the abstract features of human childhood elicit powerful emotional responses in us, even when they occur in other animals. I submit that Mickey Mouse's evolutionary road down the course of his own growth in reverse reflects the unconscious discovery of this biological principle by Disney and his artists. In fact, the emotional status of most Disney characters rests on the same set of distinctions. To this extent, the magic kingdom trades on a biological illusionâour ability to abstract and our propensity to transfer inappropriately to other animals the fitting responses we make to changing form in the growth of our own bodies.

Donald Duck also adopts more juvenile features through time. His elongated beak recedes and his eyes enlarge; he converges on Huey, Louie, and Dewey as surely as Mickey approaches Morty. But Donald, having inherited the mantle of Mickey's original misbehavior, remains more adult in form with his projecting beak and more sloping forehead.

Mouse villains or sharpies, contrasted with Mickey, are always more adult in appearance, although they often share Mickey's chronological age. In 1936, for example, Disney made a short entitled

Mickey's Rival

. Mortimer, a dandy in a yellow sports car, intrudes upon Mickey and Minnie's quiet country picnic. The thoroughly disreputable Mortimer has a head only 29 percent of body length, to Mickey's 45, and a snout 80 percent of head length, compared with Mickey's 49. (Nonetheless, and was it ever different, Minnie transfers her affection until an obliging bull from a neighboring field dispatches Mickey's rival.) Consider also the exaggerated adult features of other Disney charactersâthe swaggering bully Peg-leg Pete or the simple, if lovable, dolt Goofy.

Dandified, disreputable Mortimer (here stealing Minnie's affections) has strikingly more adult features than Mickey. His head is smaller in proportion to body length; his nose is a full 80 percent of head length. © Walt Disney Productions

As a second, serious biological comment on Mickey's odyssey in form, I note that his path to eternal youth repeats, in epitome, our own evolutionary story. For humans are neotenic. We have evolved by retaining to adulthood the originally juvenile features of our ancestors. Our australopithecine forebears, like Mickey in

Steamboat Willie

, had projecting jaws and low vaulted craniums.

Our embryonic skulls scarcely differ from those of chimpanzees. And we follow the same path of changing form through growth: relative decrease of the cranial vault since brains grow so much more slowly than bodies after birth, and continuous relative increase of the jaw. But while chimps accentuate these changes, producing an adult strikingly different in form from a baby, we proceed much more slowly down the same path and never get nearly so far. Thus, as adults, we retain juvenile features. To be sure, we change enough to produce a notable difference between baby and adult, but our alteration is far smaller than that experienced by chimps and other primates.

A marked slowdown of developmental rates has triggered our neoteny. Primates are slow developers among mammals, but we have accentuated the trend to a degree matched by no other mammal. We have very long periods of gestation, markedly extended childhoods, and the longest life span of any mammal. The morphological features of eternal youth have served us well. Our enlarged brain is, at least in part, a result of extending rapid prenatal growth rates to later ages. (In all mammals, the brain grows rapidly in utero but often very little after birth. We have extended this fetal phase into postnatal life.)

But the changes in timing themselves have been just as important. We are preeminently learning animals, and our extended childhood permits the transference of culture by education. Many animals display flexibility and play in childhood but follow rigidly programmed patterns as adults. Lorenz writes, in the same article cited above: “The characteristic which is so vital for the human peculiarity of the true manâthat of always remaining in a state of developmentâis quite certainly a gift which we owe to the neotenous nature of mankind.”

In short, we, like Mickey, never grow up although we, alas, do grow old. Best wishes to you, Mickey, for your next half-century. May we stay as young as you, but grow a bit wiser.

Cartoon villains are not the only Disney characters with exaggerated adult features. Goofy, like Mortimer, has a small head relative to body length and a prominent snout. © Walt Disney Productions

NOTHING IS QUITE

so fascinating as a well-aged mystery. Many connoisseurs regard Josephine Tey's

The Daughter of Time

as the greatest detective story ever written because its protagonist is Richard III, not the modern and insignificant murderer of Roger Ackroyd. The old chestnuts are perennial sources for impassioned and fruitless debate. Who was Jack the Ripper? Was Shakespeare Shakespeare?

My profession of paleontology offered its entry to the first rank of historical conundrums a quarter-century ago. In 1953, Piltdown man was exposed as a certain fraud perpetrated by a very uncertain hoaxer. Since then, interest has never flagged. People who cannot tell

Tyrannosaurus

from

Allosaurus

have firm opinions about the identity of Piltdown's forger. Rather than simply ask “whodunit?” this column treats what I regard as an intellectually more interesting issue: why did anyone ever accept Piltdown man in the first place? I was led to address the subject by recent and prominent news reports addingâwith abysmally poor evidence, in my opinionâyet another prominent suspect to the list. Also, as an old mystery reader, I cannot refrain from expressing my own prejudice, all in due time.

In 1912, Charles Dawson, a lawyer and amateur archeologist from Sussex, brought several cranial fragments to Arthur Smith Woodward, Keeper of Geology at the British Museum (Natural History). The first, he said, had been unearthed by workmen from a gravel pit in 1908. Since then, he had searched the spoil heaps and found a few more fragments. The bones, worn and deeply stained, seemed indigenous to the ancient gravel; they were not the remains of a more recent interment. Yet the skull appeared remarkably modern in form, although the bones were unusually thick.

Smith Woodward, excited as such a measured man could be, accompanied Dawson to Piltdown and there, with Father Teilhard de Chardin, looked for further evidence in the spoil heaps. (Yes, believe it or not, the same Teilhard who, as a mature scientist and theologian, became such a cult figure some fifteen years ago with his attempt to reconcile evolution, nature, and God in

The Phenomenon of Man

. Teilhard had come to England in 1908 to study at the Jesuit College in Hastings, near Piltdown. He met Dawson in a quarry on May 31, 1909; the mature solicitor and the young French Jesuit became warm friends, colleagues, and coexplorers.)

On one of their joint expeditions, Dawson found the famous mandible, or lower jaw. Like the skull fragments, the jaw was deeply stained, but it seemed to be as apish in form as the cranium was human. Nonetheless, it contained two molar teeth, worn flat in a manner commonly encountered in humans, but never in apes. Unfortunately, the jaw was broken in just the two places that might have settled its relationship with the skull: the chin region, with all its marks of distinction between ape and human, and the area of articulation with the cranium.

Armed with skull fragments, the lower jaw, and an associated collection of worked flints and bone, plus a number of mammalian fossils to fix the age as ancient, Smith Woodward and Dawson made their splash before the Geological Society of London on December 18, 1912. Their reception was mixed, although on the whole favorable. No one smelled fraud, but the association of such a human cranium with such an apish jaw indicated to some critics that remains of two separate animals might have been mixed together in the quarry.

During the next three years, Dawson and Smith Woodward countered with a series of further discoveries that, in retrospect, could not have been better programmed to dispel doubt. In 1913, Father Teilhard found the all-important lower canine tooth. It, too, was apish in form but strongly worn in a human manner. Then, in 1915, Dawson convinced most of his detractors by finding the same association of two thick-skulled human cranial fragments with an apish tooth worn in a human manner at a second site two miles from the original finds.

Henry Fairfield Osborn, leading American paleontologist and converted critic, wrote:

If there is a Providence hanging over the affairs of prehistoric men, it certainly manifested itself in this case, because the three fragments of the second Piltdown man found by Dawson are exactly those which we would have selected to confirm the comparison with the original typeâ¦. Placed side by side with the corresponding fossils of the first Piltdown man they agree precisely; there is not a shadow of a difference.

Providence, unbeknown to Osborn, walked in human form at Piltdown.

For the next thirty years, Piltdown occupied an uncomfortable but acknowledged place in human prehistory. Then, in 1949, Kenneth P. Oakley applied his fluorine test to the Piltdown remains. Bones pick up fluorine as a function of their time of residence in a deposit and the fluorine content of surrounding rocks and soil. Both the skull and jaw of Piltdown contained barely detectable amounts of fluorine; they could not have lain long in the gravels. Oakley still did not suspect fakery. He proposed that Piltdown, after all, had been a relatively recent interment into ancient gravels.

But a few years later, in collaboration with J.S. Weiner and W.E. le Gros Clark, Oakley finally considered the obvious alternativeâthat the “interment” had been made in this century with intent to defraud. He found that the skull and jaw had been artificially stained, the flints and bone worked with modern blades, and the associated mammals, although genuine fossils, imported from elsewhere. Moreover, the teeth had been filed down to simulate human wear. The old anomalyâan apish jaw with a human craniumâwas resolved in the most parsimonious way of all. The skull

did

belong to a modern human; the jaw was an orangutan's.

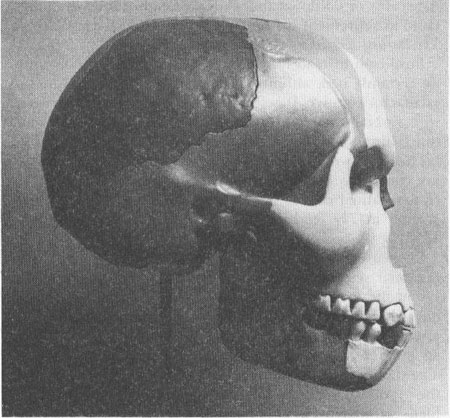

Skull of Piltdown Man.

COURTESY OF THE

A

MERICAN

M

USEUM OF

N

ATURAL

H

ISTORY

But who had foisted such a monstrous hoax upon scientists so anxious for such a find that they remained blind to an obvious resolution of its anomalies? Of the original trio, Teilhard was dismissed as a young and unwitting dupe. No one has ever (and rightly, in my opinion) suspected Smith Woodward, the superstraight arrow who devoted his life to the reality of Piltdown and who, past eighty and blind, dictated in retirement his last book with its chauvinistic title,

The Earliest Englishman

(1948).

Suspicion instead has focused on Dawson. Opportunity he certainly had, although no one has ever established a satisfactory motive. Dawson was a highly respected amateur with several important finds to his credit. He was overenthusiastic and uncritical, perhaps even a bit unscrupulous in his dealings with other amateurs, but no direct evidence of his complicity has ever come to light. Nevertheless, the circumstantial case is strong and well summarized by J.S. Weiner in

The Piltdown Forgery

(Oxford University Press, 1955).

Supporters of Dawson have maintained that a more professional scientist must have been involved, at least as a coconspirator, because the finds were so cleverly faked. I have always regarded this as a poor argument, advanced by scientists largely to assuage their embarrassment that such an indifferently designed hoax was not detected sooner. The staining, to be sure, had been done consummately. But the “tools” had been poorly carved and the teeth crudely filedâscratch marks were noted as soon as scientists looked with the right hypothesis in mind. Le Gros Clark wrote: “The evidences of artificial abrasion immediately sprang to the eye. Indeed so obvious did they seem it may well be askedâhow was it that they had escaped notice before.” The forger's main skill consisted in knowing what to leave outâdiscarding the chin and articulation.

In November 1978, Piltdown reappeared prominently in the news because yet another scientist had been implicated as a possible coconspirator. Shortly before he died at age ninety-three, J. A. Douglas, emeritus professor of geology at Oxford, made a tape recording suggesting that his predecessor in the chair, W.J. Sollas, was the culprit. In support of this assertion, Douglas offered only three items scarcely ranking as evidence in my book: (1) Sollas and Smith Woodward were bitter enemies. (So what. Academia is a den of vipers, but verbal sparring and elaborate hoaxing are responses of differing magnitude.) (2) In 1910, Douglas gave Sollas some mastodon bones that could have been used as part of the imported fauna. (But such bones and teeth are not rare.) (3) Sollas once received a package of potassium bichromate and neither Douglas nor Sollas's photographer could figure out why he had wanted it. Potassium bichromate was used in staining the Piltdown bones. (It was also an important chemical in photography, and I do not regard the alleged confusion of Sollas's photographer as a strong sign that the professor had some nefarious usages in mind.) In short, I find the evidence against Sollas so weak that I wonder why the leading scientific journals of England and the United States gave it so much space. I would exclude Sollas completely, were it not for the paradox that his famous book,

Ancient Hunters

, supports Smith Woodward's views about Piltdown in terms so obsequiously glowing that it could be read as subtle sarcasm.

Only three hypotheses make much sense to me. First, Dawson was widely suspected and disliked by some amateur archeologists (and equally acclaimed by others). Some compatriots regarded him as a fraud. Others were bitterly jealous of his standing among professionals. Perhaps one of his colleagues devised this complex and peculiar form of revenge. The second hypothesis, and the most probable in my view, holds that Dawson acted alone, whether for fame or to show up the world of professionals we do not know.

The third hypothesis is much more interesting. It would render Piltdown as a joke that went too far, rather than a malicious forgery. It represents the “pet theory” of many prominent vertebrate paleontologists who knew the man well. I have sifted all the evidence, trying hard to knock it down. Instead, I find it consistent and plausible, although not the leading contender. A.S. Romer, late head of the museum I inhabit at Harvard and America's finest vertebrate paleontologist, often stated his suspicions to me. Louis Leakey also believed it. His autobiography refers anonymously to a “second man,” but internal evidence clearly implicates a certain individual to anyone in the know.

It is often hard to remember a man in his youth after old age imposes a different persona. Teilhard de Chardin became an austere and almost Godlike figure to many in his later years; he was widely hailed as a leading prophet of our age. But he was once a fun-loving young student. He knew Dawson for three years before Smith Woodward entered the story. He may have had access, from a previous assignment in Egypt, to mammalian bones (probably from Tunisia and Malta) that formed part of the “imported” fauna at Piltdown. I can easily imagine Dawson and Teilhard, over long hours in field and pub, hatching a plot for different reasons: Dawson to expose the gullibility of pompous professionals; Teilhard to rub English noses once again with the taunt that their nation had no legitimate human fossils, while France reveled in a superabundance that made her the queen of anthropology. Perhaps they worked together, never expecting that the leading lights of English science would fasten upon Piltdown with such gusto. Perhaps they expected to come clean but could not.

Teilhard left England to become a stretcher bearer during World War I. Dawson, on this view, persevered and completed the plot with a second Piltdown find in 1915. But then the joke ran away and became a nightmare. Dawson sickened unexpectedly and died in 1916. Teilhard could not return before the war's end. By that time, the three leading lights of British anthropology and paleontologyâArthur Smith Woodward, Grafton Elliot Smith, and Arthur Keithâhad staked their careers on the reality of Piltdown. (Indeed they ended up as two Sir Arthurs and one Sir Grafton, largely for their part in putting England on the anthropological map.) Had Teilhard confessed in 1918, his promising career (which later included a major role in describing the legitimate Peking man) would have ended abruptly. So he followed the Psalmist and the motto of Sussex University, later established just a few miles from Piltdownâ“Be still, and knowâ¦.”âto his dying day. Possible. Just possible.

All this speculation provides endless fun and controversy, but what about the prior and more interesting question: why had anyone believed Piltdown in the first place? It was an improbable creature from the start. Why had anyone admitted to our lineage an ancestor with a fully modern cranium and the unmodified jaw of an ape?

Indeed, Piltdown never lacked detractors. Its temporary reign was born in conflict and nurtured throughout by controversy. Many scientists continued to believe that Piltdown was an artifact composed of two animals accidentally commingled in the same deposit. In the early 1940s, for example, Franz Weidenreich, perhaps the world's greatest human anatomist, wrote (with devastating accuracy in hindsight): “

Eoanthropus

[âdawn man,' the official designation of Piltdown] should be erased from the list of human fossils. It is the artificial combination of fragments of a modern human braincase with orang-utanglike mandible and teeth.” To this apostasy, Sir Arthur Keith responded with bitter irony: “This is one way of getting rid of facts which do not fit into a preconceived theory; the usual way pursued by men of science is, not to get rid of facts, but frame theory to fit them.”