The Paleo Diet for Athletes (16 page)

Read The Paleo Diet for Athletes Online

Authors: Loren Cordain,Joe Friel

Saturated fatty acids are the simplest of the three major families of fatty acids because they contain no double bonds between carbon atoms in the backbone of the molecule. Consequently, each carbon atom is fully “saturated” with hydrogen atoms.

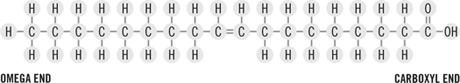

Figure 5.2

is a schematic diagram of a saturated fatty acid called lauric acid, which is given the technical designation of 12:0; it contains 12 carbon atoms and 0 double bonds between the carbon atoms. It also has an omega end and a carboxyl end. (You’ll see why knowing which end is which is important when we talk about differences between omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids.)

The other major dietary saturated fatty acids are 14:0 (myristic acid), 16:0 (palmitic acid), and 18:0 (stearic acid). Of all of these, 12:0, 14:0, and 16:0 raise blood cholesterol levels, whereas 18:0 is neutral. Both 12:0 and 14:0 are found in relatively small concentrations in fatty foods, so 16:0 is the primary fatty acid in butter, cheese, lard, bacon, salami, and other fatty meats responsible for elevating blood cholesterol. However, because it (16:0) also simultaneously elevates the “good” HDL cholesterol, the most recent meta-analyses (large population studies) show saturated fats in general to be minor risk factors for heart disease. I came up

to a similar conclusion in a book chapter I wrote in 2006 that analyzed the amounts of dietary saturated fats in 229 hunter-gatherer societies.

Monounsaturated Fatty Acids

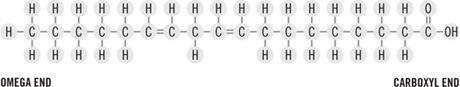

FIGURE 5.3

Compared with saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids lower total blood cholesterol levels. They are labeled “mono” unsaturated because there is a single double bond in their carbon backbone.

Figure 5.3

is a diagram of oleic acid, also known as 18:1v9. The “v” symbol stands for “omega.” Again, “18” means that there are 18 carbons in its backbone; the “1” means there is one double bond, which is located 9 carbon molecules down from the omega end. Monounsaturated fatty acids are found in nuts, avocados, olive oil, and other oils listed in

Chapter 11

. These are some of the healthful fatty foods you want to include in your diet if you decide to up your fat intake.

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (Omega-6s)

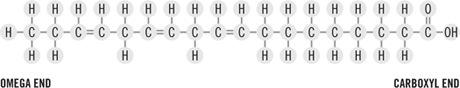

FIGURE 5.4

Polyunsaturated fatty acids are called “poly,” meaning “many,” because they contain two or more double bonds between the carbon atoms in their backbone.

Figure 5.4

illustrates linoleic acid, or 18:2v6. By now, you probably are getting the drift of this naming scheme: Linoleic acid contains 18 carbon atoms and 2 double bonds, and the last double bond is located 6 carbon atoms down from the omega end of the fatty acid backbone.

Linoleic acid is a member of the omega-6 family of polyunsaturated fatty acids and is found in high concentrations in corn oil, safflower oil, and other salad oils and processed foods made with vegetable oils. Excessive intake of omega-6 polyunsaturated fats may promote heart disease, inflammation, and certain cancers; and the typical American diet contains way too much of this fat. In

Chapter 11

, you’ll learn how to achieve just the right balance of this fat on your menu.

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (Omega-3s)

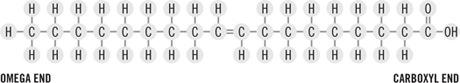

FIGURE 5.5

Almost anyone who has an interest in diet and health has heard of omega-3 fatty acids, but most people really don’t know what they are. This will change for you in about 2 seconds, now that you are becoming an accomplished lipid chemist with this tutorial. The simplest omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid is called alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), abbreviated 18:3v3. If you have been following along, you know that ALA contains 18 carbon atoms in its backbone and 3 double bonds, the last of which is 3 carbon atoms down from the omega end.

Figure 5.5

shows a diagram of this fatty acid. These diagrams are helpful in understanding the structure and names of the various fats, but they don’t tell you everything. The carbon-to-carbon bonds in their backbones are not straight (180 degrees) but form a 109-degree angle. Hence, their actual physical structures look different from these diagrammatic representations.

ALA is the simplest omega-3 fatty acid and is found in high concentrations in flaxseed and canola oils. In the body, the liver can turn ALA from flaxseed or canola oil into longer chain omega-3s such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), or 20:5v3, and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), or 22:6v3. However, this process is quite inefficient, and only less than 1 percent of ALA is turned into DHA. Most of the beneficial biological effects of omega-3 fatty acids result from the long chain metabolites of ALA, which are EPA and DHA. You’re better off getting your omega-3s from fish and seafood, which are rich sources of both EPA and DHA.

A few recent human experiments suggest that omega-3 fatty acids may have few performance enhancing effects; nevertheless, literally thousands of scientific experiments have shown that these fatty acids promote good health. Omega-3s are potent anti-inflammatory agents comparable or superior to aspirin. In one study of 10 elite endurance athletes, by Dr. Tim Mickleborough at Indiana University, dietary fish oil supplementation proved to be highly effective in reducing exercise-induced constriction of the airways leading to the lungs. This isn’t of interest only to elite athletes: Exercise-induced asthma (EIA) is a real problem that may affect as much as 10 percent of the general population. If that includes you, then increasing your dietary intake of omega-3s not only makes sense but also may be essential medicine. Even if you don’t suffer symptoms of EIA, your long-term health will benefit in many ways if you get more of these highly therapeutic fatty acids into your diet.

Trans Fatty Acids

FIGURE 5.6

Trans fatty acids have been in the news for decades, so you may know that they raise your blood cholesterol levels and increase your risk for heart disease. Trans fatty acids most frequently are formed when vegetable oils are solidified into margarine or shortening by a process called hydrogenation. Consequently, hydrogenated or partially hydrogenated vegetable oils contain trans fatty acids. European scientists participating in a large clinical trial called the TransLinE Study showed that trans fatty acids can also be formed when vegetable oils are deodorized. Careful deodorizing prevents the formation of trans fatty acids. So, when you buy vegetable oil, make sure the label guarantees that the product is trans fat-free.

Trans fatty acids are isomers of normally occurring fatty acids—meaning that they have the same molecular weight as a normal fatty acid but a slightly different structure. We’ve already talked about oleic acid, a monounsaturated fat labeled 18:1v9 or, more precisely, 18:1v9 cis. That means the hydrogen atoms adjacent to the single double bond are on the same side (cis).

Figure 5.6

shows a trans fatty acid designated 18:1v9 trans. It is called a “trans” fatty acid because the hydrogen atoms about the double bond are on opposite sides. This specific trans fatty acid is also known as trans elaidic acid and is the bad guy responsible for the cholesterol-raising and other adverse health effects of trans fatty acids found in margarine and shortening. The deodorization of vegetable oils produces trans isomers of 18:3v3 (ALA), which also negatively affect your blood lipid profile. Do yourself a favor and keep these nasty fats out of your diet.

POTASSIUM/SODIUM BALANCE

In the typical US diet, we get almost 10 grams of salt per day. Because salt is made up of sodium and chloride, this translates into a daily intake of 3.5 grams of sodium and 6.5 grams of chloride. Most people know that the sodium part of salt is not good for health, particularly when we get too much of it. But few people have a clue that the chloride portion is also problematic (more on this later). Consider the ratio of potassium to sodium in the average American diet: Because our average daily potassium intake is a paltry 2.6 grams, the ratio (2.6:3.5) is 0.74. One of the reasons we have so little potassium in our diets is that in the United States we simply eat too few fruits and veggies, the richest sources of this element. Ninety-one percent of the US population does not meet the USDA recommendation of two to three daily servings of fruit and three to five daily servings of vegetables. In stark contrast, a modern-day Paleo diet, like that outlined in

Chapter 1

, contains 9 grams of potassium and 0.7 gram of sodium, for a ratio of 12.5. From hundreds of computer simulations of modern-day Paleo diets, we have found the ratio of potassium to sodium is always greater than 5, whereas in the typical US diet, it is always less than 1.

This complete inversion of the Paleo potassium/sodium ratio may produce a number of potential health problems that may hurt your race-day performance. Similar to the effects of having too few omega-3 fatty acids in your diet, excessive sodium also worsens exercise-induced asthma symptoms. Experiments from our laboratory and Dr. Mickleborough’s at Indiana University in both humans and animals show beyond a shadow of a doubt that reducing dietary salt for those with EIA is therapeutic. This strategy won’t eliminate EIA, but it will vastly improve symptoms. Similarly, if you suffer from hypertension or osteoporosis, lowering the salt and upping the fruit and veggies in your diet may prove helpful. For athletes training or racing long distances in heat, we don’t suggest eliminating salt completely but, rather, using it moderately and following the guidelines established in

Chapters 2

,

3

, and

4

.

ACID/BASE BALANCE

Most athletes and many nutrition experts alike are unaware of the concept of dietary acid/base balance and how it may affect health, well-being, and athletic performance. All foods after digestion report to the kidney as either acid or base (see

Table 4.4

. If the diet produces a net metabolic acidosis, then the kidney must buffer this acid load with stored alkaline base. Ultimately, alkaline base can come from calcium salts in the bones. Alternatively, more acid can be excreted in the urine by the muscles breaking down and releasing more of the amino acid glutamine. Over the long haul, both effects may hurt your performance. Accelerated bone mineral loss increases the likelihood of stress fractures—clearly a liability in your training schedule.