The Paleo Diet for Athletes (14 page)

Read The Paleo Diet for Athletes Online

Authors: Loren Cordain,Joe Friel

A 150-pound athlete training 15 hours a week would need to take in about 135 grams of protein a day (150 x 0.9), according to

Table 4.8

. Assuming 20 percent of that comes from assorted vegetables, fruits, fruit juices, sports bars, and sports drinks consumed

throughout the day, including during the workout, another 108 grams of protein would be needed that day. To get that from animal sources, he could eat:

4 ounces of cod

6 ounces of turkey breast

4 ounces of chicken

Those foods would provide all of the additional protein and contain 44.5 grams of the all-important essential amino acids for our theoretical athlete. The total energy eaten to get these nutrients would be 454 calories. To get the same amount of protein by combining grains and beans, he would have to eat all of the following in one day:

1 cup of tofu

1 cup of kidney beans

6 slices of whole wheat bread

1 cup of navy beans

1½ cups of corn

1 cup of red beans

1 cup of brown rice

2 bagels

2 tablespoons of peanut butter

Our athlete had better like beans and have a huge appetite! The above requires eating an additional 2,300 calories that day—more than five times as much as when eating animal products—just to get 108 grams of protein. Eating grains and legumes to get daily protein is not only very inefficient, but, far worse, the vegetarian athlete will come up short on essential amino acids—even if he or she can stomach all those beans and grains.

STAGE V AND FAT

Just as there are good and bad sources of carbohydrate and protein, there are fats and oils you should pursue in your daily diet and certain others to avoid. The desirables include omega-3 polyunsaturated and monounsaturated types. As described earlier in this chapter, lowering the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 has positive implications for reducing the likelihood of inflammation, a persistent problem for athletes. Omega-6s, while necessary for health, are more than abundant in our modern diet. This fat is common in vegetable oils such as soybean, peanut, cottonseed, safflower, sunflower, sesame, and corn. Most snack foods and many grain products, including breads and bagels, rely heavily on vegetable oils due to their low cost.

Monounsaturated fats should also be included in the athlete’s diet because of their health benefits, including lowering cholesterol and triglyceride levels, thinning the blood, preventing fatal heartbeat irregularities, and reducing the risk of breast cancer. Remember that health always comes before fitness. Good sources of monounsaturated fat are avocados, nuts, and olive oil.

Avoid the fats found in abundance in whole dairy foods and feedlot-raised animals, especially beef, and trans fat found in many of the foods in our grocery stores—not only snack foods but also many bread products, peanut butter, margarine, and packaged meals. Steer clear of trans fat, referred to as “partially hydrogenated” oil on food labels, whenever possible. Trans fat increases LDL (the “bad” cholesterol associated with heart disease) and also decreases your body’s production of HDL (the “good” cholesterol linked with a low incidence of heart disease). That’s a double whammy best avoided.

PART II

N

UTRITION

101: U

NDERSTANDING

B

ASIC

C

ONCEPTS

CHAPTER 5

F

OOD AS

F

UEL DURING

E

XERCISE

DIETARY ORIGINS

Upon introduction to the Paleo Diet concept, many people assume that there was a single universal diet that all Stone Age people ate. Nothing could be further from the truth. In the 5 million to 7 million years since the evolutionary split between apes and hominins (primates who walk upright on two feet), as many as 20 or more different species of hominins may have existed. Their diets varied by latitude, season, climate, and food availability. But there was one universal characteristic: They all ate minimally processed wild plant and animal foods. In the Introduction, we told you all about the foods they couldn’t have consumed; in

Chapter 8

, we will show you the evidence for the food that they ate. But in the meantime, it’s important to understand how the current Western diet differs from theirs and how these differences may affect exercise performance.

If you contrast the average American diet to hunter-gatherer diets (even at their most extreme deviations), the standard American diet falls outside the hunter-gatherer range for certain crucial nutritional characteristics. By examining the diets of more than 200 hunter-gatherer societies, we have found that the typical Western diet varies from ancestral hunter-gatherer diets in these seven key features:

1. Macronutrient balance

2. Glycemic load

3. Fatty acid balance

4. Potassium/sodium balance

5. Acid/base balance

6. Fiber intake

7. Trace nutrient density

MACRONUTRIENT BALANCE AND GLYCEMIC LOAD

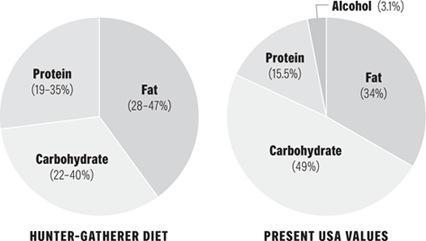

Figure 5.1 compares the macronutrient composition (protein, fat, carbohydrate) of hunter-gatherer and typical US diets. Note that in hunter-gatherer diets, protein is universally elevated at the expense of carbohydrate, while the diets usually contained more fat than what we

get. However, the types of fat they consumed were healthful omega-3 and monounsaturated fats, and certain polyunsaturated and saturated fats. But the important issue here for the athlete is the carbohydrate story. Not only was the carbohydrate content of their diet lower, but the quality of their carbs was worlds apart from what most of us eat.

FIGURE 5.1

Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load

One quality of any carbohydrate food is its glycemic index. The glycemic index, a scale that rates how much certain foods raise blood sugar levels compared with glucose, was developed by Dr. David Jenkins at the University of Toronto in 1981. Sometimes white bread, which has a glycemic index of 100, is used as the reference food rather than glucose. One of the shortcomings of the original glycemic index is that it only compares equal quantities of carbohydrate (usually 50 grams) among foods to evaluate the blood glucose response. It doesn’t take into account the total amount of carbohydrate in a typical serving. This limitation has created quite a bit of confusion. For instance, watermelon has a glycemic index (GI) of 72, while a milk chocolate candy bar tops out with a GI of only 43. Does that mean we should eat candy bars rather than fruit? Of course not! The candy bar is a much more concentrated source of carbohydrate (sugar) than watermelon is. You would have to eat only 3 ounces of the chocolate to get 50 grams of carbohydrate, whereas you would have to eat a half pound of watermelon to get 50 grams of carbs. To overcome this limitation, scientists at Harvard University in 1997 proposed using a new scale called the glycemic load, defined as the GI multiplied by the carbohydrate content in a typical serving. The glycemic load effectively equalized the playing field and made real-world food comparisons possible.

Almost all processed foods made from refined grains and sugars have quite high glycemic loads, whereas virtually all fresh fruits and veggies have very low glycemic loads (see

Table 5.1

). The Web site

www.glycemicindex.com

helps you determine the GI and glycemic load of almost any food.

TABLE 5.1

Comparison of Glycemic Index and Load of Refined and Unrefined Foods (100 g portions)

| WESTERN REFINED FOODS | ||

| Food | Glycemic Index | Glycemic Load |

| Crisped rice cereal | 88 | 77.3 |

| Jelly beans | 80 | 74.5 |

| Cornflakes | 84 | 72.7 |

| Life Savers | 70 | 67.9 |

| Rice cakes | 82 | 66.9 |

| Table sugar (sucrose) | 65 | 64.9 |

| Shredded wheat cereal | 69 | 57.0 |

| Graham crackers | 74 | 56.8 |

| Grape-Nuts cereal | 67 | 54.3 |

| Cheerios cereal | 74 | 54.2 |

| Rye crisp bread | 65 | 53.4 |

| Vanilla wafers | 77 | 49.7 |

| Corn chips | 73 | 46.3 |

| Mars bar | 68 | 42.2 |

| Shortbread cookies | 64 | 41.9 |

| Granola bar | 61 | 39.3 |

| Angel food cake | 67 | 38.7 |

| Bagel | 72 | 38.4 |

| Doughnut | 76 | 37.8 |

| White bread | 70 | 34.7 |

| Waffles | 76 | 34.2 |

| 100% bran cereal | 42 | 32.5 |

| Whole wheat bread | 69 | 31.8 |

| Croissant | 67 | 31.2 |

| UNREFINED TRADITIONAL FOODS | ||

| Food | Glycemic Index | Glycemic Load |

| Parsnips | 97 | 19.5 |

| Baked potato | 85 | 18.4 |

| Boiled millet | 71 | 16.8 |

| Boiled broad beans | 79 | 15.5 |

| Boiled couscous | 65 | 15.1 |

| Boiled sweet potato | 54 | 13.1 |

| Boiled brown rice | 55 | 12.6 |

| Banana | 53 | 12.1 |

| Boiled yam | 51 | 11.5 |

| Boiled garbanzo beans | 33 | 9 |

| Pineapple | 66 | 8.2 |

| Grapes | 43 | 7.7 |

| Kiwifruit | 52 | 7.4 |

| Carrots | 71 | 7.2 |

| Boiled beets | 64 | 6.3 |

| Boiled kidney beans | 27 | 6.2 |

| Apple | 39 | 6.0 |

| Boiled lentils | 29 | 5.8 |

| Pear | 36 | 5.4 |

| Watermelon | 72 | 5.2 |

| Orange | 43 | 5.1 |

| Cherries | 22 | 3.7 |

| Peach | 28 | 3.1 |

| Peanuts | 14 | 2.6 |