The Oxford History of World Cinema (5 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

also the forerunners of electronic image-making. The first experiments in transmitting

images by a television-type device are in fact as old as the cinema: Adriano de Paiva

published his first studies on the subject in 1880, and Georges Rignoux seems to have

achieved an actual transmission in 1909. Meanwhile certain 'pre-cinema' techniques

continued to be used in conjunction with cinema proper during the years around 1900-5

when the cinema was establishing itself as a new mass medium of entertainment and

instruction, and lantern slides with movement effects continued for a long time to be

shown in close conjunction with film screenings.

Magic lantern, film, and television, therefore, do not constitute three separate universes

(and fields of study), but belong together as part of a single process of evolution. It is

none the less possible to distinguish them, not only technologically and in terms of the

way they were diffused, but also chronologically. The magic lantern show gradually gives

way to the film show at the beginning of the twentieth century, while television emerges

fully only in the second half of the century. In this succession, what distinguishes cinema

is on the one hand its technological base -- photographic images projected in quick

succession giving the illusion of continuity -- and on the other hand its use prevailingly as

large-scale public entertainment.

THE BASIC APPARATUS

Films produce their illusion of continuous movement by passing a series of discrete

images in quick succession in front of a light source enabling the images to be projected

on a screen. Each image is held briefly in front of the light and then rapidly replaced with

the next one. If the procedure is rapid and smooth enough, and the images similar enough

to each other, discontinuous images are then perceived as continuous and an illusion of

movement is created. The perceptual process involved was known about in the nineteenth

century, and given the name persistence of vision, since the explanation was thought to lie

in the persistence of the image on the retina of the eye for long enough to make

perception of each image merge into the perception of the next one. This explanation is no

longer regarded as adequate, and modern psychology prefers to see the question in terms

of brain functions rather than of the eye alone. But the original hypothesis was

sufficiently fertile to lead to a number of experiments in the 1880s and 1890s aimed at

reproducing the so-called persistence of vision effect with sequential photographs.

The purposes of these experiments were various. They were both scientific and

commercial, aimed at analysing movement and at reproducing it. In terms of the

emergence of cinema the most important were those which set out to reproduce

movement naturally, by taking pictures at a certain speed (a minimum of ten or twelve per

second and generally higher) and showing them at the same speed. In fact throughout the

silent period the correspondence between camera speed and projection was rarely perfect.

A projection norm of around 16 pictures ('frames') per second seems to have been the

most common well into the 1920s, but practices differed considerably and it was always

possible for camera speeds to be made deliberately slower or faster to produce effects of

speeded-up or slowed-down motion when the film was projected. It was only with the

coming of synchronized sound-tracks, which had to be played at a constant speed, that a

norm of 24 frames per second (f.p.s.) became standard for both camera and projector.

First of all, however, a mechanism had to be created which would enable the pictures to

be exposed in the camera in quick succession and projected the same way. A roll of

photographic film had to be placed in the camera and alternately held very still while the

picture was exposed and moved down very fast to get on to the next picture, and the same

sequence had to be followed when the film was shown. Moving the film and then

stopping it so frequently put considerable strain on the film itself -- a problem which was

more severe in the projector than in the camera, since the negative was exposed only once

whereas the print would be shown repeatedly. The problem of intermittent motion, as it is

called, exercised the minds of many of the pioneers of cinema, and was solved only by

the introduction of a small loop in the threading of the film where it passed the gate in

front of the lens (see inset).

FILM STOCK

The moving image as a form of collective entertainment -what we call 'cinema' --

developed and spread in the form of photographic images printed on a flexible and

semitransparent celluloid base, cut into strips 35 mm. wide. This material -- 'film' -- was

devised by Henry M. Reichenbach for George Eastman in 1889, on the basis of inventions

variously attributed to the brothers J. W. and I. S. Hyatt ( 1865), to Hannibal Goodwin

( 1888), and to Reichenbach himself. The basic components of the photographic film used

since the end of the nineteenth century have remained unchanged over the years. They

are: a transparent

base,

or

support;

a very fine layer of

adhesive substrate

made of

gelatine; and a light-sensitive

emulsion

which makes the film opaque on one side. The

emulsion generally consists of a suspension of silver salts in gelatine and is attached to

the base by means of the layer of adhesive substrate. The base of the great majority of 35

mm. films produced before February 1951 consists of

cellulose nitrate,

which is a highly

flammable substance. From that date onwards the nitrate base has been replaced by one of

cellulose acetate,

which is far less flammable, or increasingly by

polyester.

From early

times, however, various forms of 'safety' film were tried out, at first using cellulose

diacetate (invented by Eichengrun and Becker as early as 1901), or by coating the nitrate

in non-flammable substances. The first known examples of these procedures date back to

1909. Safety film became the norm for non-professional use after the First World War.

The black and white negative film used up to the mid1920s was so-called orthochromatic.

It was sensitive to ultraviolet, violet, and blue light, and rather less sensitive to green and

yellow. Red light did not affect the silver bromide emulsion at all. To prevent parts of the

scene from appearing on the screen only in the form of indistinct dark blobs, early

cinematographers had to practise a constant control of colour values on the set. Certain

colours had to be removed entirely from sets and costumes. Actresses avoided red

lipstick, and interior scenes were shot against sets painted in various shades of grey. A

new kind of emulsion called

panchromatic

was devised for Gaumont by the Eastman

Kodak Company in 1912. In just over a decade it became the preferred stock for all the

major production companies. It was less light-sensitive in absolute terms than

orthochrome, which meant that enhanced systems of studio lighting had to be developed.

But it was far better balanced and allowed for the reproduction of a wider range of greys.

In the early days, however, celluloid film was not the only material tried out in the

showing of motion pictures. Of alternative methods the best known was the Mutoscope.

This consisted of a cylinder to which were attached several hundred paper rectangles

about 70 mm. wide. These paper rectangles contained photographs which, if watched in

rapid sequence through a viewer, gave the impression of continuous movement. There

were even attempts to produce films on glass: the Kammatograph ( 1901) used a disc with

a diameter of 30 cm., containing some 600 photographic frames arranged in a spiral.

There were experiments involving the use of translucent metal with a photographic

emulsion on it which could be projected by reflection, and films with a surface in relief

which could be passed under the fingers of blind people, on a principle similar to Braille.

FORMATS

The 35 mm. width (or 'gauge') for cellulose was first adopted in 1892 by Thomas Edison

for his Kinetoscope, a viewing device which enabled one spectator at a time to watch

brief segments of film. The Kinetoscope was such a commercial success that subsequent

machines for reproducing images in movement adopted 35 mm. as a standard format.

This practice had the support of the Eastman Company, whose photographic film was 70

mm. wide, and therefore only had to be cut lengthwise to produce film of the required

width. It is also due to the mechanical structure of the Kinetoscope that 35 mm. film has

four perforations, roughly rectangular in shape, on both sides of each frame, used for

drawing the film through the camera and projector. Other pioneers at the end of the

nineteenth century used a different pattern. The Lumière brothers, for example, used a

single circular perforation on each side. But it was the Edison method which was soon

adopted as standard, and remains so today. It was the Edison company too who set the

standard size and shape of the 35 mm. frame, at approximately 1 in. wide and 0.75 in.

high.

Although these were to become the standards, there were many experiments with other

gauges of film stock, both in the early period and later. In 1896 the Prestwich Company

produced a 60 mm. film strip, an example of which is preserved in the National Film and

Television Archive in London, and the same width (but with a different pattern of

perforations) was used by Georges Demený in France. The Veriscope Company in

America introduced a 63 mm. gauge; one film in this format still survives -- a record of

the historic heavyweight championship fight between Corbett and Fitzsimmons in 1897.

Around the same time Louis Lumière also experimented with 70 mm. film which yielded

a picture area 60 mm. wide and 45 mm. high. All these systems encountered technical

problems, particularly in projection. Though some further experiments took place towards

the end of the silent period, the use of wide gauges such as 65 and 70 mm. did not come

into its own until the late 1950s.

More important than any attempts to expand the image, however, were those aimed at

reducing it and producing equipment suitable for non-professional users.

In 1900 the French company Gaumont began marketing its 'Chrono de Poche', a portable

camera which used 15 mm. film with a single perforation in the centre. Two years later

the Warwick Trading Company in England introduced a 17.5 mm. film for amateurs,

designed to be used on a machine called the Biokam which (like the first Lumière

machines) doubled as camera, printer, and projector; this idea was taken up by Ernemann

in Germany and then by Pathé in France in the 1920s. Meanwhile in 1912 Pathé had also

introduced a system that used 28 mm. film on a non-flammable diacetate base and had a

picture area only slightly smaller than 35 mm.

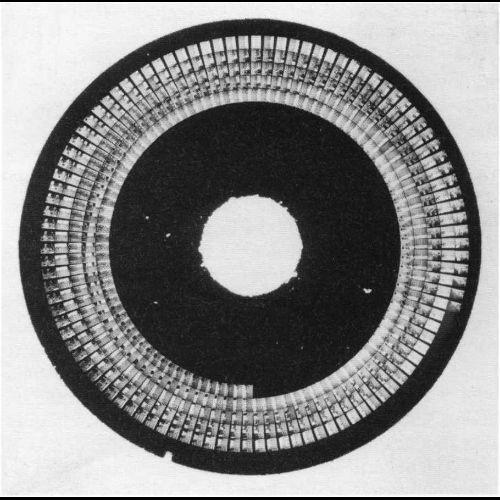

An alternative to celluloid film, the Kammatograph (c. 1900) used a glass disc with the film frames arranged in a spiral

The amateur gauge

par excellence,

however, was 16 mm. on a non-flammable base,

devised by Eastman Kodak in 1920. In its original version, known as the Kodascope, this

worked on the reversal principle, producing a direct positive print on the original film