The Oxford History of World Cinema (30 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

or so features are no longer extant. Only a few sequences survive of North of Hudson

Bay, one of two Mix films under the direction of Fox's premier Western director at the

time, John Ford. Fortunately, several good examples of his work do remain. The Great K

& A Train Robbery ( 1926) gives a typical impression of Mix in his prime. It opens with a

spectacular stunt in which Tom slides down a cable to the bottom of a gorge, and ends,

after skirmishes on top of moving trains, with an epic first-fight in an underground cavern

between Tom and about a dozen villains. He captures them all.The Fox publicity machine

worked hard at constructing a biography which was as colourful as Mix's screen

performance. It was variously claimed that his mother was part-Cherokee, that he fought

with the army in Cuba during the Spanish - American War, taking part in the famous

charge up San Juan Hill with Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders, and also fought in the

Boxer Rebellion in Peking. None of these things was true. Mix did not leave the United

States during his brief army service, which ended ignominiously with his desertion when

he got married.By all accounts Mix often found it difficult to separate out fact from

faction. He followed the show-business tradition of Western heroes initiated by Buffalo

Bill Cody. Both on and off screen he became an increasingly flamboyant figure, with his

huge white hat, embroidered western suits, diamond-studded belts, and hand-tooled boots.

Though, unlike Hart, Mix had been a genuine working cowboy, his roots were in the Wild

West show and the rodeo, and at periodic points in his career he returned to touring in live

shows, including circuses. Mix's career was past its peak by the time sound came to the

Western, but the singing cowboys of the 1930s, with their fanciful costumes and Arcadian

vision of western ranch life, were his direct descendants, His last film, the serial The

Miracle Rider, was a rather sad affair. Five years later, short of money, he tried to

persuade Fox to finance a come-back. His old friend John Ford had to explain that the

picture business had passed him by. Later that year his car overturned at a bend outside

Florence, Arizona, killing him instantly.

Riders of the Purple Sage ( 1925)

EDWARD BUSCOMBE

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

Ranch Life in Great Southwest

( 1909); The Heart of Texas Ryan ( 1917); The Wilderness Trail ( 1919); Sky High

( 1922); Just Tony ( 1922); Tom Mix in Arabia ( 1922); Three Jumps Ahead ( 1923); The

Lone Star Ranger ( 1923); North of Hudson Bay ( 1923); Riders of the Purple Sage

( 1925); The Great K & A Trian Robbery ( 1926); Rider of Death Valley ( 1932)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brownlow, Kevin ( 1979), The War, the West and the Wilderness.

Mix, Paul E. ( 1972), The Life and Legend of Tom Mix.

THE SILENT FILM

Tricks and Animation

DONALD CRAFTON

Contrary to popular belief, the history of animation did not begin with Walt Disney's

sound film Steamboat Willie in 1928. Before then there was a popular tradition, a film

industry, and a vast number of films -- including nearly 100 of Disney's -- which pre-

dated the so-called classic studio period of the 1930s.

The general history of the animated film begins with the use of transient trick effects in

films around the turn of the century. As distinct genres emerged (Westerns, chase films,

etc.) during 1906-10, there appeared at the same time films made all or mostly by the

animation technique. Since most movies were a single reel, there was little programmatic

difference between the animated films and others. But as the multi-reel film trend

progressed after around 1912, with only a handful of exceptions, animated films retained

their one-reel-or-less length. At the same time they began to be associated in the

collective mind of producers and audiences with comic strips, primarily because they

adapted already-existing heroes from the popular printed media and 'signed' the films in

the cartoonists' names, although the artists generally had no involvement in the

production. Until the First World War, animation was a thoroughly international

phenomenon, but after about 1915 the producers in the United States dominated the world

market. Although there were many attempts at indigenous European production, the

1920s remained the dominion of the American character series: Mutt and Jeff, Koko the

Clown, Farmer Al Falfa, and Felix the Cat. Of all the ways in which the formation of the

animated film paralleled feature production, the most notable was the cartoon's

assimilation of the 'star system' in the 1920s, during which animation studios created

recurring protagonists who were analogous to human stars.

DEFINITIONS

The animated film can be broadly defined as a kind of motion picture made by arranging

drawings or objects in a manner that, when photographed and projected sequentially on

movie film, produces the illusion of controlled motion. In practice, however, definitions

of what constitutes animation are inflected by a variety of technical, generic, thematic,

and industrial considerations.

Technique

Animated images were being made long before cinematography was invented in the

1890s; as David Robinson ( 1991) has shown, making drawings move was a prototype for

making photographs move and has a history that diverges from that of cinema. If we

restrict our discussion to theatrical animated films, then 1898 is a possible starting-point.

Although there is no acceptable evidence to verify either claim, the animation technique

might have been discovered independently by J. Stuart Blackton in the United States and

by Arthur Melbourne-Cooper in England. Each claimed to have been first to exploit an

alternative way of using the motion picture camera: manipulating objects in the field of

vision and exposing only one or a few frames at a time in order to mimic the illusion of

motion created by ordinary cinematography. In projection, it makes no difference whether

the individual frames have been exposed 16-24 times per second or exposed with an

indefinite interval; the illusion of motion is the same. So the traditional technologically

based definition of animation as constructing and shooting frame by frame is clearly

inadequate. All movies are composed, exposed, and projected frame by frame (otherwise

the image would be blurred). The defining technical factor seems to be in the intended

effect to be produced on the screen.

Genre

It was not until about 1906 that the animated film became a recognizable mode of

production. Humorous Phases of Funny Faces ( Blackton, 1906) depicted an artist's hand

sketching caricatures which then moved their eyes and mouths. This was done by

exposing a couple of frames, erasing the chalk drawing, redrawing it slightly modified,

then exposing more frames. The impression was created that the drawings were moving

by themselves. Émile Cohl 's

Fantasmagorie

( 1908) also showed an artist's drawings

moving on their own, achieving independence from him. Gradually these conventions

were consolidated into characteristic themes and iconography which set this kind of film-

making apart from other novelty productions. Before about 1913, the items that were

animated tended to be objects -- toys, puppets, and cut-outs -- but slowly the proportion of

drawings to objects increased until, after 1915, 'animated cartoons', that is, drawings

(especially comic strips), were understood as constituting the genre.

Themes and conventions

Should animation be defined by characteristic themes? Some commentators have

identified 'creating the illusion of life' as animation's essential metaphor. Another

recurring motif is the representation of the animators (or their symbolic substitutes)

within the films. The confusion between the universe represented in the films and the

'real' world of the animator and the film audience is another persistent theme.

Animated films can also be defined culturally. It is often imagined that animation is a

humorous genre, aimed mainly at children, and indeed children have always been (and

continue to be) a large part of the audience for the cartoon film. But animation consists of

more than cartoons, and it should not be forgotten that even the classic cartoon was made

for general audiences, not a juvenile audience alone. A cultural definition of animation

would therefore need to take into account the kind of humour it represents but also its

association (particularly in the early period) with magic and the supernatural, and its

ability to function as a repository of psychological processes such as fantasy or infantile

regression.

Industry

Produced in specialized units (whether in studios or in artisanal workshops), animated

films soon came to have a particular place in the film programme. The cartoon was the

moment in the programme which foregrounded neither 'reality' (newsreel or

documentary) nor human drama (the feature), but humour, slapstick spectacle and

narrative, animal protagonists, and fantastic events, produced by drawings or puppets.

PRECURSORS

The 'trick film' was one of the earliest film genres. While identified primarily with the

work of the French magician turned film-maker Georges Méliès, many such films were

made in several countries between 1898 and 1908. During photography the camera would

be stopped, a change made (for example, a girl substituted for a skeleton), then

photography resumed.

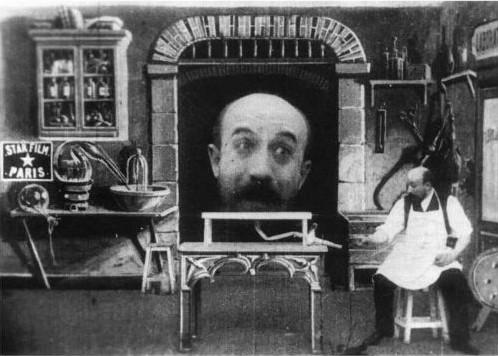

A precursor of the animated film: a shot from Georges Méliès's 'trick film' The Man with the Rubber Head (

L'Homme à

la tête en caoutchouc,

1902)

Méliès himself apparently did not make extensive use of frame-by-frame animation. For

that one must turn to James Stuart Blackton, one of the founders of the Vitagraph

Company and maker of what is usually taken to be the first true animated cartoon,

Humorous Phases of Funny Faces. In 1906-7, Blackton made half a dozen films which

employed animated effects. His most influential was The Haunted Hotel ( February

1907), which was a smash hit in Europe, primarily because of its close-up animation of

tableware. Among film-makers profoundly influenced by Blackton's Vitagraph work were

Segundo de Chomón of Spain (working in France), Melbourne-Cooper and Walter R.

Booth ( England), and, in the United States, Edwin S. Porter at Edison and Billy Bitzer at

Biograph.

In these trick films animation was basically-a trick. Like the sleight of hand in a magic

film, the animated footage in these short films was a way to thrill, amuse, and incite the

curiosity of the spectators. As the novelty wore off, some producers -- notably Blackton

himself -abandoned this kind of film. Others expanded and modified it, leading to the

creation of the new autonomous film genre.

ARTISANS: COHL AND MCCAY

Émile Cohl had been a caricaturist and comic strip artist before discovering cinema

around the age of 50. From 1908 to 1910 he worked on at least seventy-five films for the

Gaumont Company, contributing animated footage to most of them. A rather obsessive

artist, Cohl quickly devised numerous animation procedures which remain fundamental,

such as illuminated animation stands with vertically mounted electrically driven cameras,