The Oxford History of World Cinema (11 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

flirts with his female customer. A cut-in approximates his view of her ankle as she raises

her skirt in tantalizing fashion. This close-up insert is an example not only of the visual

pleasure afforded by the 'cinema of attractions' but of the early cinema's voyeuristic

treatment of the female body. Despite the fact that their primary purpose is not to

emphasize narrative developments, these shots' attribution to a character in the film

distinguishes them from the totally unmotivated closer views in The Great Train Robbery

and Raid on a Coiner's Den.

The editing strategies of the pre- 1907 'cinema of attractions'were primarily designed to

enhance visual pleasure rather than to tell a coherent, linear narrative. But many of these

films did tell simple stories and audiences undoubtedly derived narrative, as well as

visual, pleasure. Despite the absence of internal strategies to construct spatial-temporal

relations and linear narratives, the original audiences made sense of these films, even

though modern viewers can find them all but incoherent. This is because the films of the

'cinema of attractions' relied heavily on their audiences' knowledge of other texts, from

which the films were directly derived or indirectly related. Early film-makers did learn

how to make meaning in a new medium, but were not working in a vacuum. The cinema

had deep roots in the rich popular culture of the age, drawing heavily during its infant

years upon the narrative and visual conventions of other forms of popular entertainment.

The pre-1907 cinema has been accused of being 'non-cinematic' and overly theatrical, and

indeed film-makers like Mélièlis were heavily influenced by nondramatic theatrical

practices, but for the most part lengthy theatrical dramas provided an inappropriate model

for a medium that began with films of less than a minute, and only became an important

source of inspiration as films grew longer during the transitional period. As the first

Edison Kinetoscope films illustrate, vaudeville, with its variety format of unrelated acts

and lack of concern for developed stories, constituted a very important source material

and the earliest film-makers relied upon media such as the melodrama and pantomime

(emphasizing visual effects rather than dialogue), magic lanterns, comics, political

cartoons, newspapers, and illustrated song slides.

Magic lanterns, early versions of slide projectors often lit by kerosene lamps, proved a

particularly important influence upon films, for magic lantern practices permitted the

projection of 'moving pictures', which set precedents for the cinematic representation of

time and space. Magic lanterns employed by travelling exhibitors often had elaborate

lever and pulley mechanisms to produce movement within specially manufactured slides.

Long slides pulled slowly through the slide holder produced the equivalent of a cinematic

pan. Two slide holders mounted on the same lantern permitted the operator to produce a

dissolve by switching rapidly between slides. The use of two slides also permitted

'editing', as operators could cut from long shots to close-ups, exteriors to interiors, and

from characters to what they were seeing. Grandma's Reading Glasses, in fact, derives

from a magic lantern show. Magic lantern lectures given by travelling exhibitors such as

the Americans Burton Holmes and John Stoddard provided precedents for the train and

travelogue films, the lantern illustrations often intercutting exterior views of the train,

interior views of the traveller in the train, and views of scenery and of interesting

incidents.

In addition to mimicking the visual conventions of other media, film-makers derived

many of their films from stories already well known to the audience. Edison advertised its

Night before Christmas ( Porter, 1905) by saying the film 'closely follows the time-

honored Christmas legend by Clement Clarke Moore'. Both Biograph and Edison made

films of the hit song 'Everybody Works but Father'. Vitagraph based its Happy Hooligan

series on a cartoon tramp character whose popular comic strip ran in several New York

newspaper Sunday supplements. Many early films presented synoptic versions of fairly

complex narratives, their producers presumably depending upon their audiences'pre-

existing knowledge of the subject-matter rather than upon cinematic conventions for the

requisite narrative coherence. L'Épopée napoléonienne ('The Epic of Napoleon', 1903-4

Pathé) presents Napoleon's life through a series of tableaux, drawing upon well-known

historical incidents (the coronation, the burning of Moscow) and anecdotes ( Napoleon

standing guard for the sleeping sentry) but with no attempt at causal linear connection or

narrative development among its fifteen shots. In similar fashion, multi-shot films such as

Ten Nights in a Barroom ( Biograph, 1903) and Uncle Tom's Cabin (Vitagraph, 1903)

presented only the highlights of these familiar and oftperformed melodramas, with shot

connections provided not by editing strategies but by the audiences' knowledge of

intervening events. The latter film, however, appears to be one of the earliest to have

intertitles. These title cards, summarizing the action of the shot which followed, appeared

at the same time as the multi-shot film, around 1903-4, and seem to indicate a recognition

on the part of the producers of the necessity for internally rather than externally derived

narrative coherence.

EXHIBITION

Cinema initially existed not as a popular commercial medium but as a scientific and

educational novelty. The cinematic apparatus itself and its mere ability to reproduce

movement constituted the attraction, rather than any particular film. In many countries,

moving picture machines were first seen at world's fairs and scientific expositions: the

Edison Company had planned to début its Kinetoscope at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair

although it failed to assemble the machines in time, and moving picture machines were

featured in several areas of the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris.

Fairly rapidly, cinema exhibition was integrated into pre-existing venues of 'popular

culture' and 'refined culture', although the establishment of venues specifically for the

exhibition of films did not come until 1905 in the United States and a little later

elsewhere. In the United States, films were shown in the popular vaudeville houses,

which by the turn of the century catered to a reasonably well-to-do audience willing to

pay 25 cents for an afternoon or evening's entertainment. Travelling showmen, who

lectured on educational topics, toured with their own projectors and showed films in local

churches and operahouses, charging audiences in large metropolitan areas the same $2

that it cost to see a Broadway show. Cheaper and more popular venues included tent

shows, set up at fairs and carnivals, and temporarily rented store-fronts, the forerunners of

the famous nickelodeons. Early film audiences in the United States, therefore, tended to

be quite heterogeneous, and dominated by no one class.

Early exhibition in Britain, as in most European countries, followed a similar pattern to

the United States, with primary exhibition venues being fairgrounds, music halls, and

disused shops. Travelling showmen played a crucial role in establishing the popularity of

the new medium, making films an important attraction at fairgrounds. Given that fairs and

music halls attracted primarily working-class patrons, early film audiences in Britain, as

well as on the Continent, had a more homogeneous class base than in the United States.

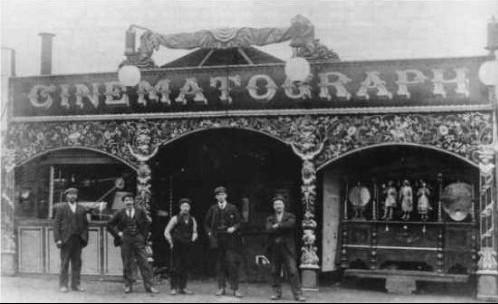

An early travelling cinema: Green's Cinematograph Show, Glasgow, 1898

Wherever films were shown, and whoever saw them, the exhibitor during this period

often had as much control over the films' meanings as did the producers themselves. Until

the advent of multi-shot films and intertitles, around 1903-4, the producers supplied the

individual units but the exhibitor put together the programme, and single-shot films

permitted decision-making about the projection order and the inclusion of other material

such as lantern slide images and title cards. Some machines facilitated this process by

combining moving picture projection with a stereopticon, or lantern slide projector,

allowing the exhibitor to make a smooth transition between film and slides. In New York

City, the Eden Musée put together a special show on the Spanish-American War, using

lantern slides and twenty or more films from different producers. While still primarily an

exhibitor, Cecil Hepworth suggested interspersing lantern slides with films and 'stringing

the pictures together into little sets or episodes' with commentary linking the material

together. When improvements in the projector permitted showing films that lasted more

than fifty seconds, exhibitors began splicing twelve or more films together to form

programmes on particular subjects. Not only could exhibitors manipulate the visual

aspects of their programmes, they also added sound of various kinds, for, contrary to

popular opinion, the silent cinema was never silent. At the very least, music, from the full

orchestra to solo piano, accompanied all films shown in the vaudeville houses. Travelling

exhibitors lectured over the films and lantern slides they projected, the spoken word

capable of imposing a very different meaning on the image from the one that the producer

may have intended. Many exhibitors even added sound effects -- horses' hooves, revolver

shots, and so forth-and spoken dialogue delivered by actors standing behind the screen.

By the end of its first decade of existence, the cinema had established itself as an

interesting novelty, one distraction among many in the increasingly frenetic pace of

twentieth-century life. Yet the fledgeling medium was still very much dependent upon

pre-existing media for its formal conventions and story-telling devices, upon somewhat

outmoded individually-driven production methods, and upon pre-existing exhibition

venues such as vaudeville and fairs. In its next decade, however, the cinema took major

steps toward becoming the mass medium of the twentieth century, complete with its own

formal conventions, industry structure, and exhibition venues.

Bibliography

Balio, Tino (ed.) ( 1985),

The American Film Industry

.

Barnes, John ( 1976).

The Beginnings of the Cinema in England

.

Bordwell, David, Staiger, Janet, and Thompson, Kristin ( 1985),

The Classical Hollywood

Cinema

.

Chanan, Michael ( 1980),

The Dream that Kicks

.

Cherchi Paolo Usai, and Codelli, Lorenzo (eds.) ( 1990),

Before Caligari

.

Cosandey, Roland, Gaudreault, André, and Gunning, Tom (eds.) ( 1992),

Une invention

du diable?

Elsaesser, Thomas (ed.) ( 1990),

Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative

.

Fell, John L. ( 1983),

Film before Griffith

.

--- ( 1986),

Film and the Narrative Tradition

.

Gunning, Tom ( 1986), "The Cinema of Attractions".

Holman, Roger (ed.) ( 1982),

Cinema 1900-1906: An Analytic Study

.

Low, Rachael, and Manvell, Roger ( 1948),

The History of the British Film, 1896-1906

.

Musser, Charles ( 1990),

The Emergence of Cinema

.

--- ( 1991),

Before the Nickelodeon

.

Transitional Cinema

ROBERTA PEARSON

Between 1907 and 1913 the organization of the film industry in the United States and

Europe began to emulate contemporary industrial capitalist enterprises. Specialization

increased as production, distribution, and exhibition became separate and distinct areas,

although some producers, particularly in the United States, did attempt to establish

oligopolistic control over the entire industry. The greater length of films, coupled with the

unrelenting demand from exhibitors for a regular infusion of new product, required this

standardization of production practices, as well as an increased division of labour and the

codification of cinematic conventions. The establishment of permanent exhibition sites

aided the rationalization of distribution and exhibition procedures as well as maximizing