The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (25 page)

Read The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor Online

Authors: Jake Tapper

Tags: #Terrorism, #Political Science, #Azizex666

A guard at Observation Post Warheit then called in: other Afghans, definitively with weapons and a radio, were peering down the mountain.

Gooding now reversed his decision, persuaded that the insurgents above were controlling confederates below. “Permission to engage,” he told Keating.

Keating’s men fired. Both sides shot back and forth; within forty-five minutes, Apaches were on the scene. The insurgents took cover in the homes of Kamdeshis, and the Apaches took the fight to them. Intelligence would later come in indicating that several of the insurgents had been wounded and were subsequently evacuated to Pakistan. More immediately, however, the troops of 3-71 Cav became aware that innocent Afghans had also been hurt in the action: six civilians, aged three to forty, had been cut up by shrapnel from the Apache’s 30-millimeter barrage. Their families took the wounded to Observation Post Warheit, and 3-71 Cav had them medevacked to Bagram.

The next day, nearly three dozen Kamdesh elders came down to the PRT to express their anger over the incident. They met with Feagin and Gooding in a building that was still under construction.

“You told us when you came here that you would not hurt innocent and peaceful people,” said one, speaking through a translator.

26

“You have big guns and helicopters with good technology, surely you can tell the difference between those who are innocent and those who are not. You told us if we helped you, the Americans would not harm us. We are prisoners in our villages now!”

Feagin explained that there had been “no intent to target anyone but our enemy. If the enemy continues to fight us, many more will die. I am certain.”

At that moment, gunfire sounded in the distance.

“This is part of the problem,” Feagin said, motioning in the direction of the fire. “The only thing the enemy can bring is fear, intimidation, and death.” He reminded the elders that the six wounded Kamdeshis had been transported to Bagram and were receiving exemplary medical care.

“Mack” took this opportunity to weigh in. Mack was a CIA case officer who had come to the Kamdesh base with some others from his world; they’d built a little cabin there and started their own information-collection business. Most of the time, Mack tried to keep a low profile. This was not one of those times. A muscular former Special Forces soldier, he told the assembled group a story about a neighbor he’d once had at his farm back in the States, whose ill-behaved dog posed a problem. Things got so bad, he said, that he had to ask his neighbor to put the dog down. When the neighbor refused, Mack took matters into his own hands. The implication was, of course, that he and his friends would likewise put down the bad dogs of the valley—the insurgents—if the Kamdesh elders didn’t take care of them themselves.

The story did not go over well. Bad dogs? The elders seemed revolted by the metaphor: dogs were reviled in this part of the world. In some cases, insurgents were brothers or sons to these elders, and their actions were motivated by the desire to protect their village. These were not rabid beasts. Don’t use analogies, the intelligence collector Adam Boulio reminded himself. They don’t translate.

A few days after the shura, Boulio went to the Papristan section of Kamdesh Village to photograph the damage caused by the Apaches and to record the names of those villagers who intended to file claims. He took pictures of bullet-riddled walls and broken windows, but as the hours passed, more and more Kamdeshis began making what seemed to him obviously bogus claims, holding up shoddy mattresses, broken washbasins, and other junk and blaming what was clearly ordinary squalor on the helicopters. Boulio took it all down anyway, noting which losses he thought were real.

Despite Boulio’s attempts to smooth things over with the Kamdeshis, Gooding would come to think of the Apache attack and the ill-fated shura as calamitous setbacks in the counterinsurgency effort. In his view, 3-71 Cav never managed to repair the damage these incidents caused.

In a reflective mood, Ben Keating wrote to his father, “I’ve struggled during quiet times with the question of my mortality. I don’t fear death and during my most honest moments I really don’t assume its nearness to me…. I still believe that God has a plan for my life that extends beyond this deployment; but I’m also very confident that this is a path He has set me on and that I’m treating it in a manner He asks of me. When the bullets start flying all of those thoughts are banished and I just act—further evidence to me that He is with me.”

Whether or not the Lord was with Ben Keating, many of the officers of 3-71 Cav increasingly felt that some of the Americans with

them

were leading the mission down an infernal path. No one doubted the motives of Snyder and his Special Forces troops or any of the other special-operations teams that moved in and out of the region. (Mack and his CIA officers were another, and bizarre, matter.) But their actions were sometimes messy, and 3-71 Cav troops had to clean up after them.

There was nothing 3-71 Cav could do about that, however. At Forward Operating Base Naray, a call would come in that “Task Force Blue”—a code name for Navy SEALs—would be arriving in a certain area in two hours, and the 3-71 troops would just have to try to stay out of the way. Questions about the propriety of specific missions were then left to be answered by conventional forces that had had nothing to do with the operations themselves—some of which involved acts committed over the border in Pakistan. CIA teams and Special Forces troops would kill men who they said were insurgent leaders, and who in most cases almost surely were—but when they weren’t, it was 3-71 Cav that felt the heat.

For some, collateral damage was a fact of warfare that was as acceptable as the recoil of a gun.

Led by Staff Sergeant Adam Sears, the Hoosier who’d been on the landing zone when Fenty’s Chinook crashed, four Humvees containing members of Able Troop’s 2nd Platoon left the Kamdesh outpost one October day to investigate a tip that there was an IED under a small bridge about a mile down the road to the east. The squad found nothing at the location in question, so the drivers began turning their vehicles around to return to the base. It was a difficult process, as they had to hit the sweet spot in steering: the road was narrow, but turning the front wheels too sharply could lock up the truck’s gearbox.

As fate would have it, one of the sergeants did exactly that, so Sears sent Sergeant Nick Anderson back to the outpost in another vehicle to fetch the particular tool needed to work on the gearbox; he was accompanied by Michael Hendy, whose own Humvee kept stalling. As Anderson made the tight turn in to the gate of the outpost, his Humvee’s gearbox seized up as well, and another truck had to come tow it out of the entry control point. Anderson and Hendy grabbed two other Humvees, the proper tool, and a mechanic and went back down the road to where the others were waiting.

It was a gorgeous day, and the men were enjoying the warmth of the sun on their faces. Sometimes it was easy to get lost in those bucolic surroundings and forget the existence of the enemy—and sometimes the men needed to do just that, needed to seek refuge in a momentary lapse in memory, though generally the troops were alert, knowing that otherwise they would make a ripe target.

And make a target they did. Within minutes, an RPG exploded near the Humvees. The troops scurried behind the trucks, taking cover and returning fire. The insurgents were up the mountain next to the road. “Where the fuck is Bozman?” Sears shouted. “Where the fuck is Bozman?” As the fire-support officer for the platoon, Private First Class Nathan Bozman, then in a different Humvee, was in charge of calling in the grids to the mortar team at the Kamdesh outpost. He calculated the proper grid data to give to the mortarmen, after which they pummeled the hills with 120-millimeter mortar fire, shredding the enemy’s general location. The engagement ended, and Sears led the platoon back to the outpost.

The next day, Captain Matt Gooding was told by some of his troops that two local men who worked at the outpost hadn’t shown up that morning because their nephew, who was about eleven years old, had been killed by the U.S. mortars fired the day before. The locals said the boy had been innocently walking his cow and had no connection to the insurgents at all—he was just a blameless child, killed by the foreigners who were there purportedly to help them, to protect them.

This was the first anyone from 3-71 Cav had heard about a little boy’s having been killed in the firefight, and besides bothering Gooding on a personal, emotional level, it concerned him as a commander. Such a killing could have a huge impact on us, Gooding thought. What if tomorrow

no

workers show up? What if the incident turns all of Kamdesh Village against us?

Sears, Bozman, and the others involved in the firefight felt no remorse. They’d been attacked, and they’d returned fire. It was as simple as that. The bad guys were the ones responsible for the kid’s death.

It was different for Gooding. While he hadn’t personally fired the mortars, he’d approved the action. It was his first experience, albeit indirect, of killing a civilian, and while he knew that Able Troop had fully abided by the Rules of Engagement, the child’s death still upset him. Yes, it was likely that the kid had been helping the insurgents by carrying RPGs and ammo. After all, at least five minutes had passed between the initial ambush and the mortars’ being fired, and Gooding couldn’t imagine that the boy would have just continued walking with his cow in the same direction from which RPGs were being fired. That, however, was just a hunch, and either way, he felt horrible about the whole thing. Indeed, the grief he felt was as powerful as it might have been if he’d killed one of his own children’s classmates, or if he’d run over the boy himself with his car. He emailed his wife, expressing his despair.

“It’s not the same,” she emailed back. “You’re not to blame. You and your men didn’t tell the bad guys to ambush you. You had to defend yourselves.”

Higher-level officers in the field had some discretionary funds—through the Commanders’ Emergency Response Program, or CERP—and for this type of casualty, the Pentagon-approved condolence payment was approximately $3,000 U.S. per lost life. The Kamdesh elders okayed this grant to the uncles, and two days later, with the utmost solemnity, Gooding paid them that sum in the local currency.

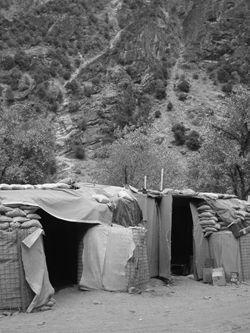

As winter approached, Gooding assigned Netzel to supervise the buildup of the camp in preparation for what would assuredly be tough weather, made tougher for those at the PRT by the fact that in the coming months, their post would occasionally be impossible to reach by either air or road. Phones and Internet service were among the camp’s few truly modern conveniences, communication lines being a high priority, but otherwise it was a bare-bones affair. In dire need of improvement were the preexisting traditional—and uncomfortable—Nuristan buildings, as well as the dozen or so bunkers topped with lumber that were used as barracks. Netzel hired local Afghans to build new structures made of wood, concrete, cement, and rock. Locals and soldiers installed bunk beds with two-inch-thick mattresses, an outhouse with three toilets, and makeshift urinals—informally called piss-tubes—here and there throughout the site. Some problems, Netzel couldn’t do much about: the flea infestation was so bad, for example, that some of the 3-71 Cav troops took to wearing flea collars fastened around their belt loops. There were also a few improvised pleasures, though. The Landay-Sin River was outside the wire—meaning it was off limits except on patrols—but sometimes troops would ask a local laborer to go to the riverbank, fill up a water jug, and bring it back to the post, where they would then hang it from a tree. It would bask in the sun all day, and just before sunset, the men could stand under the jug and enjoy a lukewarm shower. That was what passed for luxury at the outpost.

Subterranean homesick blues: the early flea-laden bunkers for troops at Camp Kamdesh.

(Photo courtesy of Ross Berkoff)