The Other Slavery (48 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

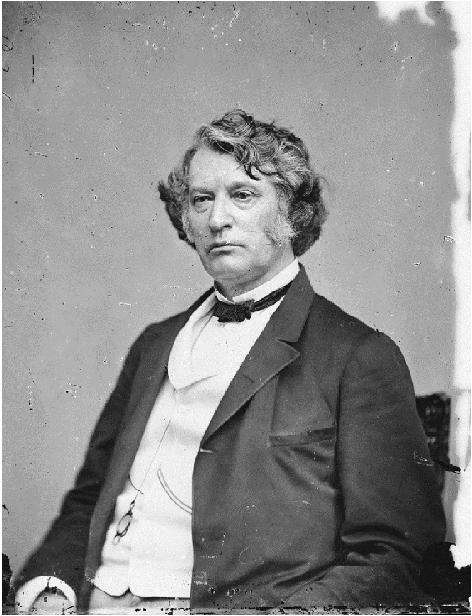

Senator Charles Sumner, circa 1865.

The same pattern of piecemeal federal involvement and local resistance to ending the other slavery characterized New Mexico. It was only because the Doolittle Commission had turned up such damning information about the condition of Indians living in the West that Secretary of the Interior James Harlan had launched a parallel investigation into New Mexico, which in turn had led Special Agent Julius K. Graves to file

a report that circulated in Congress. Things could have ended there had it not been for Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who picked up the report.

Senator Sumner was one of the staunchest free labor advocates in the entire U.S. Congress and a power to be reckoned with. His efforts to emancipate African Americans, as well as his bold ideas about forcibly reconstructing the South, are familiar to those interested in the Civil War. Far less well known are Senator Sumner’s activities on behalf of Indians. He had learned about the peonage system by corresponding with New Mexicans, and on January 3, 1867—after having read Graves’s report and pleas for vigorous action—he raised the issue on the floor of the Senate. “I think you will be astonished when you learn that the evidence is complete, showing in a Territory of the United States the existence of slavery,” Sumner informed his colleagues. “During the life of President Lincoln, I more than once appealed to him, as head of the Executive, to expel this evil from New Mexico. The result was a proclamation, and also definite orders from the War Department; but, in the face of [the] proclamation and definite orders, the abuse has continued, and, according to official evidence, it seems to have increased.” Senator Sumner then introduced a resolution to consider further legislation to stop the enslavement of Indians in New Mexico. Two months later, Congress passed “An Act to abolish and forever prohibit the System of Peonage in the Territory of New Mexico and other Parts of the United States.” The Peonage Act of 1867, as it became known, was a further elaboration of the Thirteenth Amendment. While the Thirteenth Amendment banned only “involuntary servitude,” the Peonage Act defined peonage as “the voluntary or involuntary service or labor of any persons as peons, in liquidation of any debt or obligation.” Masters often justified peonage on the grounds that it originated in a contract signed voluntarily by both parties. But the definition of peonage adopted by Congress overrode such a justification. Those who insisted on holding peons now became subject to fines of up to $5,000 and prison sentences of up to five years. In New Mexico, Governor Robert B. Mitchell publicized the Peonage Act and declared all peons free on April 14, 1867. Yet the written word was not enough to do away with the nexus of practices and customs that

had lasted for centuries. Few peons invoked the protection of this act, and fewer masters still were prosecuted.

21

More than a year passed before legislators addressed the problem of Indian bondage again. This time the trigger was money. Congress had appropriated $100,000 for the upkeep of the Bosque Redondo reservation where the Navajo nation had been confined. By early 1868, however, the appropriation had been exhausted, and the reservation was headed for catastrophe. Scurvy ran rampant; Comanches had begun attacking and carrying off herds of animals; and the interned Navajos had been unable to raise crops due to insect infestations, floods, and droughts. Faced with the specter of maintaining seven thousand Navajos in desperate circumstances, Congress set up a peace commission and dispatched it to eastern New Mexico to find a solution. Its most prominent member was Lieutenant General William T. Sherman, the second-highest-ranking officer in the United States, behind Ulysses Grant. Sherman was not known as a champion of Indian rights. In fact, over the years he had disagreed with eastern humanitarians over the army’s conduct toward Indians. But at least he made direct contact with Native Americans. As a member of the peace commission, he traveled to Bosque Redondo and in late May conferred with various Navajo chiefs. Sherman was shocked by what he saw: “I found the Bosque a mere spot of green grass in the midst of a wild desert,” the general wrote to Grant, “and the Navajos had sunk into a condition of absolute poverty and despair.” The only viable options were either to move the Navajos to Indian Territory or to return them to their homeland in northwestern New Mexico and northeastern Arizona.

22

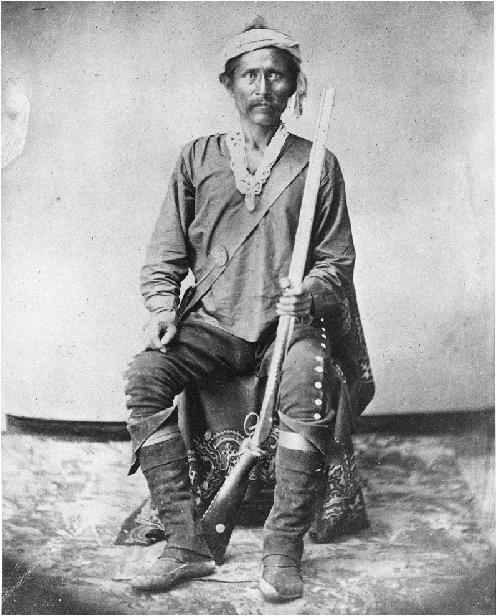

Barboncito was a member of the Coyote Pass (or Ma’iideeshgiizhnii) clan in the Canyon de Chelly. In the 1840s and 1850s, he tried to mediate between the Navajos and whites, but their conflict persisted. He participated in the Navajo attack on Fort Defiance in 1860 and subsequently tried to reach a settlement with New Mexico’s military authorities, again to no avail. He was among the last Navajo leaders to be captured and sent to the Bosque Redondo reservation.

During the negotiations, Sherman learned about the hundreds or possibly thousands of Navajos held in captivity. On May 29, the Navajo chief Barboncito got straight to the point: “I want to drop this conversation now and talk about Navajo children held as prisoners by Mexicans. Some of those present have lost a brother or a sister and I know that they are in the hands of the Mexicans. I have seen some myself.” Sherman replied that Congress, “our great council,” had passed a law that prohibited peonage, “so that if any Mexican holds a Navajo in peonage, he is liable to be put in the penitentiary.” Another commissioner from Washington, Colonel Samuel F. Tappan, then asked, “How many Navajoes are among the Mexicans now?” The Navajo man replied, “Over half of the tribe.” Tappan proceeded with the same line of inquiry: “How many have returned within the five years?” Barboncito could not tell. Sherman assured

Barboncito that he and the other commissioners would do everything possible to return the Navajo children: “All are free now in this country to go and come as they please.”

23

One month later, Congress issued Joint Resolution No. 65 authorizing Lieutenant General Sherman to use any reasonable means at his disposal to “reclaim from bondage the women and children of the Navajo, as well as other tribes now held in slavery in the Territory adjoining their homes and the reservation on which the Navajo Indians have been confined.” Sherman then ordered the military commander of New Mexico, Major General George W. Getty, to convey to the Navajos “the substance of the law” and to permit individual Navajos to search for their relatives and offer them financial support for that purpose.

24

Yet another aspect of this piecemeal process of liberating Indian slaves involved the First Judicial District Court of New Mexico. In 1868 William W. Griffin, a radical Republican and free labor advocate from Virginia bent on change, in his capacity as special commissioner of Indian affairs charged 150 individuals from the Taos area with holding Indian slaves and peons in violation of the law. His work pace was frantic. Not only did he question the masters—who readily admitted to having Indian slaves and peons—but he also requested that the victims be brought to him so that he could personally inform them that under the laws of the United States, they were “absolutely free to live where and work for whom they desired, and were at perfect liberty to go where and when they pleased, and if necessary the power of the Government would be exercised to protect them in that liberty and freedom.” Griffin was a man on a mission: “I will be able to reach and liberate every Indian held as a slave, or peon, within my district,” he wrote two months later, “and instruct them perfectly as to their rights under the laws and succeed speedily and effectively in breaking up this system of servitude so long a curse to this territory.”

25

Prompted by these proceedings, the U.S. district attorney in New Mexico began a grand jury investigation later in the year. In all, 363 individuals from Santa Fe, Taos, and Rio Arriba Counties who were suspected of holding peons or Indian slaves were subpoenaed. Griffin presented the voluminous evidence that he had gathered. However, the

crusading commissioner soon discovered that being on the right side of the law is not always enough. The jurors had peons of their own or had family members and friends who had them. Indeed, many New Mexicans were opposed to the grand jury investigation. Their point of view was best captured by an editorial in a Santa Fe newspaper: “The Navajos are a savage and barbarous people,” affirmed the

New Mexican.

“The captives from this tribe have now for years lived among civilized people; have learned the language of the country, have become Christianized . . . Most if not all of those who come under the classification of ‘Navajo captives,’ prefer to remain in homes where they have so long been domesticated, and where they possess the advantages not only of religion, but of civilized life.”

26

In the end, Commissioner Griffin succeeded in liberating 291 Indian slaves and 60 peons. Although this was a major accomplishment, the majority of owners accused of holding Indians illegally faced no consequences. In subsequent years, however, New Mexicans took fewer slaves, even if reluctantly. In 1868 the number of Navajos appearing in baptismal records was still twenty-eight, but that number dropped to seventeen in 1869 and 1870, nine in 1871, and six in 1872. Even though this evidence shows that Indian slavery diminished in New Mexico, it did not disappear.

27

One of the most striking observations one can make is that in contrast to the enormous dynamism and adaptability of the other slavery, the legal framework introduced to combat this form of bondage remained narrowly conceived and frozen in time. When legal scholar Jacobus tenBroek assessed the historical significance of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1951, right before the start of the civil rights movement, he concluded that it had played a very minor, even “insignificant” role in ending involuntary servitude among Indians in the West and others in the South. “Designed for the sweeping and basic purpose of sanctifying and nationalizing the right of freedom,” tenBroek asserted, “few indeed, have successfully invoked it.” This amendment, along with the Peonage Act of 1867, had some impact in New Mexico in the late 1860s; was used to strike down a Black Code in Alabama (1879) that facilitated

the leasing of convicts; and was invoked to nullify some statutes in Alabama (1911), Georgia (1941), and Florida (1943) that had the effect of peonizing some residents in those states. This was the sum total of the Thirteenth Amendment’s accomplishments up to 1951—a very modest harvest considering the scope of the problem.

28

In New Mexico and other parts of the West, the other slavery endured well into the twentieth century. On April 26, 1967, almost as a cruel one-hundredth anniversary commemoration of the Peonage Act, the

Albuquerque Journal

printed a picture of a smiling field worker on its front page. At the height of the civil rights movement, the photo’s caption seemed incongruous: “ALLEGED SLAVE: Abernicio Gonzales, a ranch hand in western Sandoval County is suing his employer Joe Montoya for $40,000, which he alleges is due him for wages he earned at a rate of 50 cents a day for the last 33 years. Gonzales claims he was held in peonage at the ranch.” Additional details emerged in the lawsuit. Gonzales had started working at the Cabezón Ranch in 1933 when he was thirteen years of age to repay $50 that his mother had borrowed for the wedding of an older brother. In less than three months, Gonzales worked off the debt. However, he agreed to continue working for 50 cents a day plus food, clothing, and shelter. In theory the ranch owner would deposit Gonzales’s wages in an account for his old age. But according to the plaintiff’s version, he never saw any bank statements or any other accounting of the wages. Moreover, Gonzales was not allowed to leave the ranch to seek other employment. The plaintiff also claimed that he had been punished and threatened, charges the ranch owner denied. By way of context, Gonzales’s lawyer added that in some counties of northern New Mexico, as many as forty to fifty percent of rural workers lived in what he characterized as “a state of semi-peonage.” Not everyone agreed with such a high amount. The War on Poverty administrator in New Mexico, Alex Mercure, estimated the number of agricultural workers living in “economic peonage” to about 120,000 in the entire state.

29