The Other Side of the Night (29 page)

But that was all that Senator William Alden Smith could do. He had shown to the world that there

was

a ship near the

Titanic

as the liner was sinking, and that this unknown ship had refused to answer the

Titanic

’s signals of distress. That he was convinced beyond doubt that the other ship was the

Californian

, Smith would maintain to his death. But legally his hands were bound, and he could take no action against Captain Stanley Lord.

In part of his testimony to the Senate committee, Captain Knapp, the US Navy Hydrographer, had reminded Smith first of the International Rules of Seamanship and Navigation, commonly known as the “Rules of the Road,” whereby a seaman was required “always to handle and navigate a ship in a seamanlike manner,” and directly quoted Article 29: “Nothing in the rules shall exonerate any vessel, or the owner or master or crew thereof from the consequences of any neglect to carry lights or signals or of any neglect to keep a proper lookout, or of the neglect of any precaution which may be required by the ordinary practice of seamen, or by the special circumstances of the case.”

This meant, Knapp explained, that “a captain must, in an emergency, handle or navigate his ship in a seamanlike manner.” In essence, this meant that since a ship’s master had the discretion to decide that if “special circumstances” made conditions too hazardous, he was absolved of any responsibility to respond to a distress call. To Stanley Lord, the scattering of ice in the ten miles of open water between the

Californian

and the

Titanic

were those “special circumstances”; no matter what his moral obligation, legally he was blameless.

The United States Senate investigation into the loss of the

Titanic

had run for four weeks, called eighty-two witnesses, including fifty-nine British subjects, and collected testimony, affidavits and exhibits totalling 1,198 pages. His work done, the committee’s findings duly entered into the

Congressional Record

, and his recommendations codified in Senate Bill 6976 (which would quickly pass both Houses of Congress), Senator William Alden Smith faded from the scene. It was now up to the British Board of Trade to resolve the issue of the

Californian

and Stanley Lord.

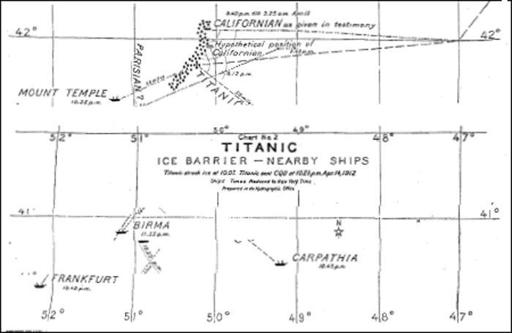

A copy of the U.S. Navy Hydrographer’s Chart submitted by Captain John Knapp at the U.S. Senate Inquiry.

Chapter 9

THE BRITISH INQUIRY

Despite its intense and probing nature—or perhaps because of it—the United States Senate Investigation into the loss of the

Titanic

was neither well regarded nor well received in Great Britain. Indeed, it is still regarded today with disdain within some circles of British maritime historians. Apparent gaffes like Senator Smith’s questions about watertight compartments or the composition of icebergs quickly made him a laughingstock among the British press. At first furious over the sheer effrontery that the committee should think that it possessed the authority to subpoena and detain British subjects, the British newspapers soon began mocking Smith, lampooning him mercilessly, calling him “a born fool.” Smith’s naivete, his earnest manner, his persistence, and most of all the questions he asked, all provided a near-endless source of material for the British satirical press and comedians. The London Hippodrome publicly offered him $50,000 to appear there and give a one hour lecture on any subject he liked, while the music hall stages began to refer to him as Senator “Watertight” Smith.

More dignified but no less strident was the legitimate British press. That the

Titanic

had been the property of an American shipping combine was ignored by a majority of the editors of Britain’s dailies—because she had been British-registered and British-crewed, she was, in their opinion, a British ship. Soon their editorial columns were running over with repetitious protests about Americans overstepping their authority, Smith’s general or specific ignorance of things nautical, the affront to Britain’s honor by the serving of subpoenas to the surviving crewmen, and so on. The magazine

Syren and Shipping

openly questioned the Senator’s sanity, while the

Morning Post

declared that “A schoolboy would blush at Mr. Smith’s ignorance.” It was the position of the

Daily Mirror

that “Senator Smith has…made himself ridiculous in the eyes of British seamen. British seamen know something about ships. Senator Smith does not.” The usually responsible

Daily Telegraph

summed up the British attitude best when it declared:

The inquiry which has been in progress in America has effectively illustrated the inability of the lay mind to grasp the problem of marine navigation. It is a matter of congratulation that British custom provides a more satisfactory method of investigating the circumstances attending a wreck.

In other words, this inquiry was something best left to the British Board of Trade, and the Americans had no business conducting such an investigation. The Senator was accused of sullying the good name and reputation of the United States Senate, of political opportunism, and of hindering the process of discovering the truth about what happened to the

Titanic

. The outpouring of indignation was so self-righteous, so consistent, so loud, and so prolonged that it began to give the impression that the British press was actually afraid of what Smith’s investigation might reveal about the British merchant marine that was better left unseen. But not all of the British press joined in the chorus of jeers and condemnation of Smith. G.K. Chesterton, writing in the

Illustrated London News

, was blunt in pointing out the differences:

It is perfectly true, as the English papers are saying, that the American papers are both what we would call vulgar and vindictive; they set the pack in full cry upon a particular man; that they are impatient of delay and eager for savage decisions; that the flags under which they march are often the rags of a reckless and unscrupulous journalism. All this is true. But if these be the American faults, it is all the more necessary to emphasize the opposite English faults. Our national evil is exactly the other way: it is to hush everything up; it is to damp everything down; it is to leave the great affair unfinished, to leave every enormous question unanswered.

The editor of

John Bull

agreed: “We need scarcely point out that the scope of such an inquiry [by the Board of Trade] is strictly limited by statute, and that its sole effect will be to shelve the scandal until public feeling has subsided.

What

a game it is!” The

Review of Reviews

, which had lost its founder on the

Titanic

, William Stead, issued the most stinging rebuke to the rest of the British papers: “We prefer the ignorance of Senator Smith to the knowledge of Mr. Ismay. Experts have told us the

Titanic

was unsinkable—we prefer ignorance to such knowledge!”

What the world was now anticipating was the inquiry by the British Board of Trade, which, as so many British papers had repeatedly pointed out during the Senate investigation, was to be a “more satisfactory method” of arriving at the truth of what had caused the

Titanic

to sink. The Inquiry would be conducted in a far more formal manner than the Senate investigation, and be constituted as a court of law under British jurisprudence.

The process began on April 29, when returning

Titanic

crewmen came down the gangway from the liner

Lapland

, which had brought them from New York to Plymouth, only to be put in a quarantine which was just short of imprisonment. They were not released until they were met by Board of Trade representatives who were waiting to take sworn statements from each of them. The Board of Trade then reviewed their statements, decided which crewmen would be called on to testify, and issued formal subpoenas to the ones chosen. The process took several days, during which the crewmen were allowed only limited contact with their families. Despite the bitterness this arrangement caused, not to mention its questionable legality, there were no confrontations between crew members and Board of Trade representatives.

The Board of Trade Court of Inquiry, as constituted by its Royal Warrant (the Crown document defining the scope of the Commission as well as its authority), was scheduled to begin sitting in session on May 3, in the London Scottish Drill Hall, near Buckingham Gate, and would consist of a President and five assessors. The assessors, all chosen for their distinguished credentials, were Captain A.W. Clarke, an Elder Brother of Trinity House; Rear Admiral the Honourable Sommerset Gough-Calthorpe, RN (Ret.); Commander Fitzhugh Lyon, RNR; J. H. Biles, Professor of Naval Architecture, University of Glasgow; and Mr. Edward Chaston, RNR, senior engineer assessor to the Admiralty. Presiding overall, indeed dominating the Court as thoroughly as William Alden Smith had dominated the Senate investigation, would be the fearsome Lord Mersey, Commissioner of Wrecks and formerly President of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court. Though Mersey would have the “assistance” of the five assessors, Mersey’s authority over the Court would be absolute: the areas of investigation, the witnesses called, the admissibility of evidence, and the final findings of the Court would all be determined by him.

John Charles Bigham, who would eventually be raised to the peerage as the 1st Viscount Mersey, was born in 1840, in Liverpool, the son of a merchant. First studying law at London University, he completed his education in Berlin and Paris, and was called to the bar in 1870 by the Middle Temple. His early practice was centered in Liverpool and consisted mostly of commercial law; in 1883, Bigham was named a Queen’s Counsel.

In 1885 Bigham turned his attention to a political career, when he ran—and lost—in a bid for Parliament as the Liberal candidate for Toxteth. A second candidacy also met with defeat in 1892, but in 1895, running as a Liberal Unionist, he was finally elected, taking his seat as the Member for the Liverpool Exchange. His political career never came to much, however, as in that same year he was appointed a judge to the Queen’s Bench; he also continued his work in business law. During the Boer War he reviewed court-martial cases, and by 1904 was presiding over the railway and canal commission. He worked in the bankruptcy courts, and reviewed courts-martial sentences handed down during the Second Boer War. In the next six years he worked in probate, divorce, and Admiralty courts, but by 1910 he had grown dissatisfied with the entire legal profession and chose to retire at the age of 70. That same year Bigham was raised to the peerage as Baron Mersey of Toxteth.

It was Lord Loreburn, the Lord Chancellor of the Asquith government, which summoned Lord Mersey out of retirement to preside over the Board of Trade inquiry into the loss of the

Titanic

. Mersey had first come to prominence as a public figure in Great Britain in 1896 when he headed an inquiry into the notorious Jameson Raid, a madcap adventure inspired by Cecil Rhodes which tried—and failed—to seize the diamond and gold fields of the Rand in South Africa. From the first, Mersey exhibited those characteristics which would come to be the hallmarks of any inquest he would conduct: he was autocratic, impatient, and not a little testy. Above all, he did not suffer fools gladly, and he was famous for the barbed rebukes he issued from the bench to witnesses or council that he considered were wasting the Court’s time. (The transcript of the

Titanic

Inquiry would record how at one point Alexander Carlisle, who had helped design the

Titanic

, related that he and an official of the White Star Line often merely rubberstamped decisions made by their superiors with the words, “Mr. Sanderson and I were more or less dummies.” Mersey replied dryly, “That has a certain verisimilitude.”)

Lord Mersey would become as closely associated with the British Inquiry into the loss of the

Titanic

as Senator Smith would be with the American investigation. Yet there was little the two men shared in common. Mersey’s roots were in the ambitious middle class, while Smith came from the working class. Mersey was very much part of the “Establishment,” while Smith took pains to stand apart from it. While Mersey was very much aware of issues roiling the different social classes, he was not driven by them in the way that Smith was. Both men, however, were deeply committed to discovering the truth, and on the bench, Mersey could be formidable in this pursuit. Off the bench, he was a complete contrast to his in-chambers persona: a soft-spoken, mild-mannered man of good taste, he readily showed himself to be well-educated and thoroughly urbane. Politically, he remained a Liberal, and his company and conversation were much appreciated in London social circles.