The Other Side of the Night (22 page)

Chapter 7

NEW YORK AND BOSTON

In New York, Thursday night, April 18, 1912, was cold and drenched with rain, the whole of New York Harbor shrouded in a thunderstorm. A crowd began gathering, mindless of the weather, on the Cunard pier around 6:00 p.m., small at first, only a few hundred, but slowly growing until by 9:00, more than 30,000 were standing along the east bank of the Hudson River. At the tip of Manhattan, huddled in the cold April downpour, another 10,000 were lining the Battery. Peering through the gloom and mist, at a few minutes past 9:00 they spotted a ship in the Ambrose Channel. It was the

Carpathia

. She was first greeted by a small fleet of steam launches, tugboats, ferry boats, and yachts, led by a large tug containing an official party of the mayor and several city commissioners.

As the

Carpathia

hove into sight the mayor’s tug let loose a shrill blast from its steam whistle, followed by the bells, whistles, and sirens of every other boat in the harbor, all in salute of the gallant Cunard ship. Captain Rostron stood on the bridge, staring out at the flotilla of boats surrounding his ship and dimly making out the throng gathered at the Cunard pier awaiting his arrival. Until this moment he had no idea, as he put it later, of “the suspense and excitement in the world:

“As we were going up Ambrose Channel, the weather changed completely, and a more dramatic ending to tragic occurrence it would be hard to conceive. It began to blow hard, rain came down in torrents, and, to complete the finale, we had continuous vivid lightning and heavy rolling thunder…. What with the wind and rain, a pitch-dark night, lightning and thunder, and the photographers taking flashlight pictures of the ship, and the explosion of the lights, it was a scene never to be effaced from one’s memory.“

At pierside, people began weeping quietly, but there was little hysteria. The most frenzied behavior was exhibited—surprise!—by the huge numbers of reporters who had gathered along with the crowd on the pier, or had gotten aboard one of the boats that had sailed into the channel to meet the

Carpathia

. When the liner stopped to pick up the pilot, five reporters were able to clamber from their boat over the railing onto the pilot boat, then attempted to force their way up the boarding ladder and onto the

Carpathia

.

Captain Rostron, once he saw the reception awaiting his ship, anticipated such an eventuality, and had stationed Third Officer Rees at the foot of the boarding ladder. Rees watched in bemused fascination as the small craft gathered around the pilot boat, the reporters shouting questions up to the decks of the

Carpathia

through megaphones, the photographers setting off their magnesium flashes as they took picture after picture. But when one of the newsmen tried to shove the pilot aside and rush up the boarding ladder himself, Rees sprang into action. Grabbing the pilot by the arm, Rees hauled him onto the boarding ladder, then turned and punched the reporter in the mouth, sending him sprawling.

“Pilot only!” he said, in case the other newsmen hadn’t got the message. Apparently one missed it, for he immediately started raving about his sister, crying about how he had to see her; when Rees didn’t believe his story, he tried to bribe the Third Officer, offering him $200 to be allowed on board. Rees refused, the boarding ladder was raised, the pilot was taken up to the bridge, and the journey up the channel resumed.

Somehow one reporter did slip aboard, but he was quickly cornered and brought to the bridge. Rostron, who had no time for such nonsense, informed the man that under no circumstances could he speak with any survivors before the

Carpathia

docked. The man was left on the bridge, after giving his word he would abide by the captain’s instructions. “I must say,” Rostron later admitted, somewhat astonished, “he was a gentleman.”

The crowd gasped with surprise when the

Carpathia

steamed past the Cunard pier toward the White Star dock and stopped there. Amidst the nearly continuous lightning and photographers’ flashes, the crew of the

Carpathia

could be seen manning several lifeboats and putting them into the water. After a moment the suddenly apprehensive crowd realized what was happening: they were the

Titanic’

s lifeboats, being duly returned to their rightful owners. It was a heartbreaking sight.

After a painfully slow turn, the

Carpathia

made her way back to the Cunard pier, and was carefully warped alongside and made fast. The canopied gangways were hauled into place, and a procession of passengers began to make their way down from the ship to the dock. After a few seconds, the stunned crowd realized that these neatly dressed people weren’t from the

Titanic.

Captain Rostron had decided that it would be unfair to his passengers to make them wait and wade through the tumult that would inevitably greet the survivors, so the

Carpathia’

s passengers disembarked first.

Then there appeared a young woman, hatless, eyes wide as she stared at the waiting crowd, the first of the

Titanic

’s survivors. At the foot of the gangway stood a solid phalanx of reporters, each one hungry for a story. Standing unrecognized among them was one man who was after the biggest story of them all: a diminutive figure flanked by two U.S. Marshals, he was Senator William Alden Smith. The appearance of the Senator and the marshals marked the beginning of a turning point in the lives of Captains Rostron and Lord. The Senator was the Chairman of the Senate subcommittee formed to investigate the loss of the

Titanic

; the lawmen were there to serve Federal subpoenas to Bruce Ismay as well as several surviving members of the

Titanic

’s crew.

A similar scene would be enacted in Boston aboard the

Californian

a few days later. It was the beginning of a process which, by the time it had run its course, would put Arthur Rostron firmly on the path that would lead him to become the Commodore of the Cunard Line; and at the same time it would slowly destroy Stanley Lord’s professional standing and career.

The

Californian

docked in Boston Harbor on April 19 virtually unnoticed and with no fanfare whatsoever. By coincidence it was the same day that the first hearings of the Senate Investigation into the

Titanic

disaster began in New York. The only incident which marked the ship’s arrival as unusual was the appearance of a corporate representative from the Leyland Line at dockside. As soon as a gangway was lowered into position he came aboard and immediately closeted himself with Lord in the captain’s cabin. No one would ever know the reason for the company representative’s visit, but it was an event that had never taken place before during Lord’s tenure as captain of the

Californian

.

That does not mean that the ship’s completion of its passage to Boston was without incident. On April 18, the day before the

Californian

was to arrive, two extraordinary incidents took place. At separate times during the day, Captain Lord called Second Officer Stone and Apprentice Officer Gibson into his quarters, and there demanded that each record a sworn, written statement describing the events of the morning of April 15. Both men complied, and when they had finished handed their statements to Lord, who promptly locked them in

Californian

’s safe. No word of explanation for his demand was offered by Lord, nor, apparently, sought by Stone or Gibson, who by now were resigned to their captain’s sometimes overbearing ways.

No sooner had the Leyland Line ship tied up at the dock and the crew allowed to go ashore than rumors began flying about the waterfront that the

Californian

had been near enough to the

Titanic

on the night of April 14–15 to watch the doomed White Star liner go down. It didn’t take long for the tale came to the ears of Boston reporters, hungry, like newsmen all across the country, for more stories about the

Titanic

. Before the day was out, the

Boston Traveler, Boston Evening Transcript,

and

Boston Globe

had sent representatives to talk to Captain Lord, who met them in the

Californian

’s chartroom.

Appearing confident and authoritative, Lord began spinning out details and snippets of information which cast him in the best possible light, and which cast carefully structured aspersions on the characters of anyone who dared suggest that the captain’s conduct in the wee hours of April 15, 1912 were anything less than exemplary. Perhaps the most revealing of these comments was Lord’s derisive observation, when asked if the

Californian

had actually been close enough to the sinking

Titanic

to see her lights, that “Seamen will say almost anything when they’re ashore.”

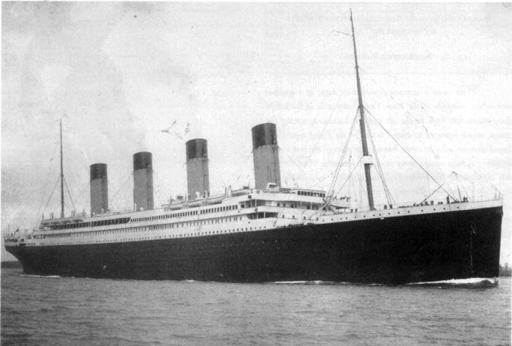

The Royal Mail Steamer (RMS)

Titanic

, the largest and most luxurious passenger liner of her day, and one of the most beautiful ships ever built.

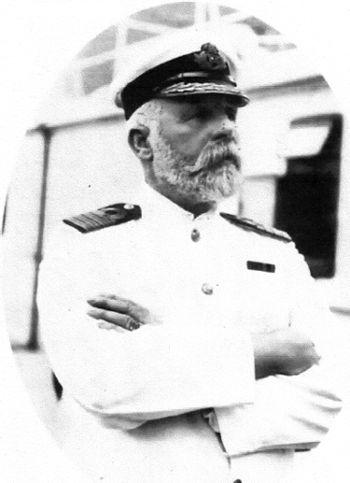

Captain Edward J. Smith. After 47 years at sea, the

Titanic

’s maiden voyage was to be his last Atlantic crossing before retirement.

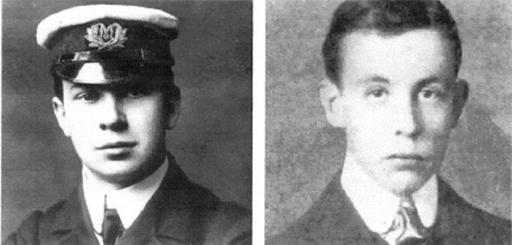

John (“Jack”) Phillips (left), the senior wireless operator aboard the

Titanic

; Harold Bride (right) was the junior operator.

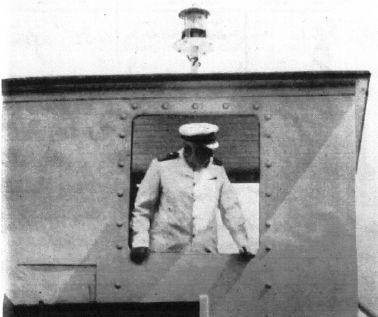

Captain Smith in the starboard bridge-wing cab of the RMS

Olympic

, the

Titanic

’s sister ship. Note the Morse lamp on top of the cab. A similar light was mounted on the port wing. The

Titanic

’s installation was identical to the

Olympic

’s.