The Origins of AIDS (9 page)

Read The Origins of AIDS Online

Authors: Pepin

Kamerun, Cameroun and Cameroons

Congo Belge/Belgisch Kongo

Created by Europeans, populated by Africans

Too many males

Around the time of the 1884–5 Berlin

conference,

Chancellor Bismarck, until then preoccupied mainly with Germany’s expansion within Europe, decided that Germany should have African colonies too. His emissaries managed to grab some nice pieces of land. While his British competitor was busy making deals in the

Niger delta,

Gustav Nachtigal, imperial consul for the west coast of Africa, signed a treaty that paved the way for the German occupation of Cameroon, which was to last only thirty years. In fact, the chiefs of the

Douala tribe had signed a

protocol with a private trader from Hamburg, who transferred his rights to Germany the very next day. It had been a pretty good week for Nachtigal

, for just a few days earlier he had signed another treaty establishing a German protectorate in

Togo.

27

conference,

Chancellor Bismarck, until then preoccupied mainly with Germany’s expansion within Europe, decided that Germany should have African colonies too. His emissaries managed to grab some nice pieces of land. While his British competitor was busy making deals in the

Niger delta,

Gustav Nachtigal, imperial consul for the west coast of Africa, signed a treaty that paved the way for the German occupation of Cameroon, which was to last only thirty years. In fact, the chiefs of the

Douala tribe had signed a

protocol with a private trader from Hamburg, who transferred his rights to Germany the very next day. It had been a pretty good week for Nachtigal

, for just a few days earlier he had signed another treaty establishing a German protectorate in

Togo.

27

Germany invested heavily in developing Kamerun’s infrastructure (ports, roads, bridges, two railways, etc.) but committed its own colonial atrocities, especially under governor

von Puttkamer, Bismarck’s nephew. Germany increased the size of Kamerun by 50% in 1911 through a controversial deal

with France: Germany abandoned its claims to

Morocco, and in exchange the French gave the Germans substantial parts of AEF. German occupation of this new territory did not last long.

At the outset of WWI, Kamerun was invaded from the

Nigerian side by British troops and from the other side by French troops from AEF assisted by soldiers from the Belgian Congo. They greatly outnumbered the Germans who fled to

Spanish Guinea. A deal was made between the victors, in which France did best, getting almost all of Kamerun less a small band of land alongside the Nigerian border. The British already had their hands full taking care of

Tanganyika and

South-West Africa, two other former German colonies.

After the war, Britain and France were given a mandate by the League of Nations to administer Cameroun Français and British Cameroons. Since our story unfolded in the southern forested areas inhabited by

P.t. troglodytes

, we will examine only the fate of Cameroun Français

.

von Puttkamer, Bismarck’s nephew. Germany increased the size of Kamerun by 50% in 1911 through a controversial deal

with France: Germany abandoned its claims to

Morocco, and in exchange the French gave the Germans substantial parts of AEF. German occupation of this new territory did not last long.

At the outset of WWI, Kamerun was invaded from the

Nigerian side by British troops and from the other side by French troops from AEF assisted by soldiers from the Belgian Congo. They greatly outnumbered the Germans who fled to

Spanish Guinea. A deal was made between the victors, in which France did best, getting almost all of Kamerun less a small band of land alongside the Nigerian border. The British already had their hands full taking care of

Tanganyika and

South-West Africa, two other former German colonies.

After the war, Britain and France were given a mandate by the League of Nations to administer Cameroun Français and British Cameroons. Since our story unfolded in the southern forested areas inhabited by

P.t. troglodytes

, we will examine only the fate of Cameroun Français

.

French rule was somewhat more benevolent in Cameroun than in neighbouring AEF. France had to provide a report each year to the League of Nations (later, the

UN), and there was some moral pressure for basic human rights to be respected. The natives could write letters of complaints to the League. Unlike their AEF counterparts, Cameroonians could not be conscripted into the French colonial army and sent to do the dirty work in other African countries, or to die for France on the battlefields of Europe or Indochina. The terms of the mandate prohibited forced labour but the Geneva-based organisation could never enforce it and many Cameroonians were requisitioned for public works

. The other major difference with AEF was the prosperity of Cameroun, built around cash crops (coffee, cocoa, rubber, timber) and the easy access to the port of Douala.

The development of roads, the railway, the healthcare system and the

urbanisation progressed more speedily than in AEF, but by the mid-1920s only Douala was considered to have a truly urban character

.

UN), and there was some moral pressure for basic human rights to be respected. The natives could write letters of complaints to the League. Unlike their AEF counterparts, Cameroonians could not be conscripted into the French colonial army and sent to do the dirty work in other African countries, or to die for France on the battlefields of Europe or Indochina. The terms of the mandate prohibited forced labour but the Geneva-based organisation could never enforce it and many Cameroonians were requisitioned for public works

. The other major difference with AEF was the prosperity of Cameroun, built around cash crops (coffee, cocoa, rubber, timber) and the easy access to the port of Douala.

The development of roads, the railway, the healthcare system and the

urbanisation progressed more speedily than in AEF, but by the mid-1920s only Douala was considered to have a truly urban character

.

To bring to an end the scandals associated with the EIC and save the country’s honour, Belgium purchased the Congo from its ailing king,

Leopold II, in 1908. He died the following year, shortly after marrying his long-time mistress Caroline, a former prostitute. This led to an appreciable improvement in the respect for basic human rights. A colonial charter was promulgated, a ministry of colonies was created and the first holder of the post,

Jules Renkin, gradually abolished the trade monopoly given to concession companies. Renkin even visited the Congo, which Leopold had never done. Fifty-two years of colonial rule followed which, like all others, was based on racism as its moral justification. After

WWI, Belgian possessions were extended to the small kingdoms of

Ruanda and

Urundi, administered like Cameroon under a League of Nations mandate

. While resource-poor Ruanda and Urundi were managed through a system of indirect rule via the traditional kings, in the Congo thousands of Belgian officials were posted at every level and in every district, in the public and private sectors.

18

Leopold II, in 1908. He died the following year, shortly after marrying his long-time mistress Caroline, a former prostitute. This led to an appreciable improvement in the respect for basic human rights. A colonial charter was promulgated, a ministry of colonies was created and the first holder of the post,

Jules Renkin, gradually abolished the trade monopoly given to concession companies. Renkin even visited the Congo, which Leopold had never done. Fifty-two years of colonial rule followed which, like all others, was based on racism as its moral justification. After

WWI, Belgian possessions were extended to the small kingdoms of

Ruanda and

Urundi, administered like Cameroon under a League of Nations mandate

. While resource-poor Ruanda and Urundi were managed through a system of indirect rule via the traditional kings, in the Congo thousands of Belgian officials were posted at every level and in every district, in the public and private sectors.

18

The Belgian Congo proved a very lucrative enterprise for Belgium. Often described as a ‘geological scandal’, the territory was rich in copper, cobalt, tin, zinc, manganese, gold, industrial diamonds and uranium to name a few. It was also very fertile, and rubber tree plantations replaced the picking of wild rubber while large quantities of coffee, cocoa, cotton and palm oil were exported. Most of the Belgian Congo’s wealth was controlled by a huge and tentacular financial holding, the Société Générale de

Belgique. Its most lucrative branch was the Union Minière du

Haut-Katanga, which operated the mines in the southern Katanga

province.

28

Belgique. Its most lucrative branch was the Union Minière du

Haut-Katanga, which operated the mines in the southern Katanga

province.

28

Through the Société Générale and other groups, there was a steady flow of resources and money in one direction: from the Congo to Belgium. The motherland kept a monopoly over the processing of the Congo’s raw products, resulting in the development of a vast industrial sector in Belgium, from metallurgy to chocolate factories. A fraction of the colony’s income trickled down to the Congolese population, through the taxes and duties paid by the companies, which funded more than half of the Belgian Congo’s budget. However, the Congolese benefited from the development of the country’s infrastructures, even if its primary goal was to facilitate the operations of private enterprises. Up to 5,000 kilometres of railways were built, roads were

kept in good condition and hydro-electric dams provided electricity to many cities. Air transportation started in 1920 with domestic flights, and by 1936 there was a service between

Brussels and Léopoldville. The proportion of the Congo’s population that lived in an urban environment increased from 6% in 1935, 15% in 1945, to 24% by 1955

.

28

–

29

kept in good condition and hydro-electric dams provided electricity to many cities. Air transportation started in 1920 with domestic flights, and by 1936 there was a service between

Brussels and Léopoldville. The proportion of the Congo’s population that lived in an urban environment increased from 6% in 1935, 15% in 1945, to 24% by 1955

.

28

–

29

Throughout central Africa, the impact of all these rapid changes on the traditional African societies was profound. Progressively, for better or worse, many Africans no longer felt bound by the customs that had regulated their lives for dozens of generations. Women acquired a degree of freedom, some of whose consequences were unexpected. While their ancestors had been generally content to procure food on a day-to-day basis and spend their evenings in endless palavers, colonisation and European examples brought materialism. Different clothes, a radio, lighting devices, a bicycle and later on a house made with cement blocks and a corrugated iron roof became the long-term goals of many workers now serving the Europeans. This hope for what was perceived as a better life lured many into the nascent cities of central Africa which, in the Belgian Congo, were quite appropriately called

centres extra-coutumiers

, centres where customs no longer held sway.

centres extra-coutumiers

, centres where customs no longer held sway.

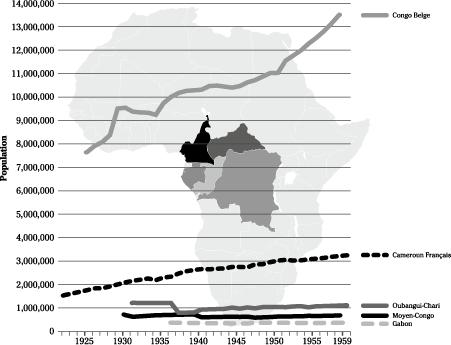

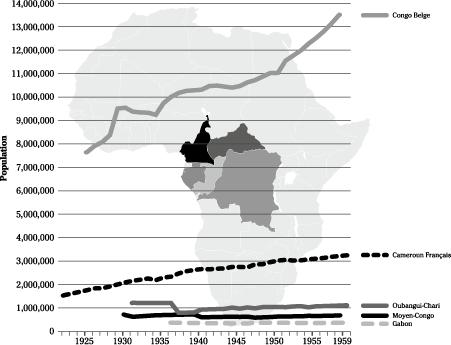

Central African colonial cities were described as having been created by Europeans and populated by Africans. In the first half of the twentieth century, this process engendered communities whose lifestyle dramatically differed from that of traditional African societies, in a way that facilitated the dissemination of sexually transmitted pathogens, including SIV

cpz

/HIV-1. Before we examine some specific cities, let us glance quickly at the populations they emerged from. Figures provided by colonial censuses, especially before 1930, need to be taken with a pinch of salt: some adult males avoided being counted for fear of taxation, forced labour or conscription, while administrators exaggerated their numbers as budgets and chances of promotion were proportional to the population. Around 1930, the population of Cameroun Français was estimated to be

2.2 million, while

it was 1.26 million in

Oubangui-Chari, 664,000 in

Moyen-Congo and only 387,000 in

Gabon (

Figure 4

; year-to-year variations over the following decades were caused by changes in the boundaries between colonies within the AEF)

. The continental part of

Equatorial Guinea had only 100,000

inhabitants, and the

Cabinda enclave of Angola even fewer. The population of the Belgian Congo, a 2.3 million km

2

subcontinent, was estimated to be 9.6 million in 1930, and 13.5 million in 1958. In all these colonies, population densities were low, generally between one and four inhabitants per km

2

.

28

–

31

cpz

/HIV-1. Before we examine some specific cities, let us glance quickly at the populations they emerged from. Figures provided by colonial censuses, especially before 1930, need to be taken with a pinch of salt: some adult males avoided being counted for fear of taxation, forced labour or conscription, while administrators exaggerated their numbers as budgets and chances of promotion were proportional to the population. Around 1930, the population of Cameroun Français was estimated to be

2.2 million, while

it was 1.26 million in

Oubangui-Chari, 664,000 in

Moyen-Congo and only 387,000 in

Gabon (

Figure 4

; year-to-year variations over the following decades were caused by changes in the boundaries between colonies within the AEF)

. The continental part of

Equatorial Guinea had only 100,000

inhabitants, and the

Cabinda enclave of Angola even fewer. The population of the Belgian Congo, a 2.3 million km

2

subcontinent, was estimated to be 9.6 million in 1930, and 13.5 million in 1958. In all these colonies, population densities were low, generally between one and four inhabitants per km

2

.

28

–

31

Figure 4

Population of colonies of central Africa, 1922–60.

Population of colonies of central Africa, 1922–60.

We will focus on the evolution of the twin cities of Brazzaville and Léopoldville (better known as ‘Brazza’ and ‘Léo’), founded at the same time by French and Belgian colonisers, and where ultimately the diversification of HIV-1 took place.

Around 1904, when Brazzaville replaced Libreville as the

AEF capital, about 250 Europeans and 5,000 Africans lived there, those necessary for the colonial administration, an embryonic private sector, and the

Catholic mission which had constituted the initial nucleus. A colonial bureaucracy was slowly developed, with a residence for the governor, buildings for the telegraph, customs, barracks, a tribunal, a prison, a local

Institut Pasteur, three dispensaries and so on. Meanwhile,

Léopoldville had been given a major boost with the opening in 1898 of the Matadi–Léo railway, which bypassed the cataracts on the Congo. Léopoldville drained a much larger chunk of

territory than its AEF counterpart. It did not make sense to manage such a huge colony out of

Boma near the mouth of the river, and in 1923 Léo became the capital of the Belgian Congo. It took a few years for this administrative decision to be implemented. This attracted a further influx of

migrants, initially house servants and low-level employees of the Belgian administration. Several thousand workers were coerced to come to Léo in the mid-1920s to build the new docks along the river.

32

Around 1904, when Brazzaville replaced Libreville as the

AEF capital, about 250 Europeans and 5,000 Africans lived there, those necessary for the colonial administration, an embryonic private sector, and the

Catholic mission which had constituted the initial nucleus. A colonial bureaucracy was slowly developed, with a residence for the governor, buildings for the telegraph, customs, barracks, a tribunal, a prison, a local

Institut Pasteur, three dispensaries and so on. Meanwhile,

Léopoldville had been given a major boost with the opening in 1898 of the Matadi–Léo railway, which bypassed the cataracts on the Congo. Léopoldville drained a much larger chunk of

territory than its AEF counterpart. It did not make sense to manage such a huge colony out of

Boma near the mouth of the river, and in 1923 Léo became the capital of the Belgian Congo. It took a few years for this administrative decision to be implemented. This attracted a further influx of

migrants, initially house servants and low-level employees of the Belgian administration. Several thousand workers were coerced to come to Léo in the mid-1920s to build the new docks along the river.

32

Brazza, the capital of an underpopulated and resource-poor colony, remained a sleepy colonial city populated by French civil servants and their house staff, missionaries, soldiers, traders and employees of a few private enterprises, while Léo thrived as the commercial hub of a wealthy colony, housing more than 600 companies by 1928

. Many of these were small family-owned businesses but there were also large employers with up to 1,000 workers, such as the Lever palm oil

company and the Otraco transportation

utility.

. Many of these were small family-owned businesses but there were also large employers with up to 1,000 workers, such as the Lever palm oil

company and the Otraco transportation

utility.

In 1921, around the time that SIV

cpz

emerged into HIV-1, only 7,000 people lived in Brazza, and 16,000 in Léo. Ten years later, Brazzaville, the largest city of AEF, had only 18,000 inhabitants while Léopoldville already had 40,000. As a proxy for colonial economic development, in 1931 there were 800 Europeans in Brazza versus 3,000 in Léo. The twin cities were followed by

Douala (22,000),

Bangui (17,000),

Yaoundé and Libreville (6,500 each), and

Pointe-Noire (5,000). Other agglomerations were in essence large villages rather than small towns. All told, less than 5% of the population of central Africa lived in an urban environment. But after this inauspicious start, the urbanisation process accelerated dramatically. Just twenty years later (1951)

, Douala had 81,500 inhabitants, Brazzaville 80,000, Bangui 65,000

, Yaoundé 30,000

,

Pointe-Noire 28,500

, Libreville 18,000 and Port-Gentil 11,000. Léopoldville was already in a category of its own with 222,000 inhabitants

.

23

,

26

,

33

–

35

cpz

emerged into HIV-1, only 7,000 people lived in Brazza, and 16,000 in Léo. Ten years later, Brazzaville, the largest city of AEF, had only 18,000 inhabitants while Léopoldville already had 40,000. As a proxy for colonial economic development, in 1931 there were 800 Europeans in Brazza versus 3,000 in Léo. The twin cities were followed by

Douala (22,000),

Bangui (17,000),

Yaoundé and Libreville (6,500 each), and

Pointe-Noire (5,000). Other agglomerations were in essence large villages rather than small towns. All told, less than 5% of the population of central Africa lived in an urban environment. But after this inauspicious start, the urbanisation process accelerated dramatically. Just twenty years later (1951)

, Douala had 81,500 inhabitants, Brazzaville 80,000, Bangui 65,000

, Yaoundé 30,000

,

Pointe-Noire 28,500

, Libreville 18,000 and Port-Gentil 11,000. Léopoldville was already in a category of its own with 222,000 inhabitants

.

23

,

26

,

33

–

35

There is nothing more conducive to large-scale

prostitution than bringing together, in a given location, a much larger number of young adult males than young women. Male sexual drive is highest in the twenty-five years after adolescence, and if monogamous or polygamous unions are not possible because of a lack of potential partners, sex will be purchased. This has been proven time and again, from the American

military bases in Asia to colonial Nairobi and the mining areas of northern Rhodesia and South Africa.

We will now examine how colonial policies created a gross gender imbalance on the banks of the Congo River, in the binational conurbation that attracted hundreds of thousands of migrants from the very areas inhabited by the

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzee, including at least one who was infected with SIV

cpz

/HIV-1.

prostitution than bringing together, in a given location, a much larger number of young adult males than young women. Male sexual drive is highest in the twenty-five years after adolescence, and if monogamous or polygamous unions are not possible because of a lack of potential partners, sex will be purchased. This has been proven time and again, from the American

military bases in Asia to colonial Nairobi and the mining areas of northern Rhodesia and South Africa.

We will now examine how colonial policies created a gross gender imbalance on the banks of the Congo River, in the binational conurbation that attracted hundreds of thousands of migrants from the very areas inhabited by the

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzee, including at least one who was infected with SIV

cpz

/HIV-1.

During the first decades of the Belgian colony, its policy was to discourage the migration of women to the cities, and only the men needed to fill vacant positions in the private or public sectors were welcome. Any concentration of unemployed men was seen as a security risk. Workers lived in labour camps and the lack of facilities discouraged them from bringing their families along. After obtaining the administrative authorisation required for any travel more than fifty kilometres away from their village (

passeport de mutation

), adult men needed a permit to live in Léo (

permis de séjour

) and another to be employed (

carte de travail

). There were regular police checks to find illegal residents, and every adult residing in Léo was fingerprinted. Needless to say, serious crimes were uncommon. An office of manpower administered work permits and found work for the jobless. Unemployment was minimal (<1% in 1946), as those without a position had to leave, and new migrants were accepted only if workers were required by employers.

36

–

38

passeport de mutation

), adult men needed a permit to live in Léo (

permis de séjour

) and another to be employed (

carte de travail

). There were regular police checks to find illegal residents, and every adult residing in Léo was fingerprinted. Needless to say, serious crimes were uncommon. An office of manpower administered work permits and found work for the jobless. Unemployment was minimal (<1% in 1946), as those without a position had to leave, and new migrants were accepted only if workers were required by employers.

36

–

38

Women’s migration to the cities was restricted on ‘moral’ grounds. With prostitution being common in the urban areas, administrative and religious authorities tried to hamper the exodus of women from the villages for fear that they would also be tempted, apparently not understanding that these very policies were driving prostitution

. It was hard to obtain a mutation passport for a

woman. The evolution of Léo’s population can be seen in

Figure 5

. In 1929, there were 26,932 adult males, 7,460 adult females, and only 2,662 children.

Father Joseph Van Wing, a Jesuit who wrote copiously about Kongo culture, described Léo as ‘clean but joyless and infinitely gloomy because of the dearth of children, a camp rather than a village’. Eventually, restrictions on the movement of women were relaxed, but the very nature of these booming cities perpetuated the imbalance. Young unmarried men were more likely than others to try their luck in the developing urban areas, while married men would go alone at first, get a steady job, find proper housing and accumulate savings before asking their families to follow them.

17

,

39

,

40

. It was hard to obtain a mutation passport for a

woman. The evolution of Léo’s population can be seen in

Figure 5

. In 1929, there were 26,932 adult males, 7,460 adult females, and only 2,662 children.

Father Joseph Van Wing, a Jesuit who wrote copiously about Kongo culture, described Léo as ‘clean but joyless and infinitely gloomy because of the dearth of children, a camp rather than a village’. Eventually, restrictions on the movement of women were relaxed, but the very nature of these booming cities perpetuated the imbalance. Young unmarried men were more likely than others to try their luck in the developing urban areas, while married men would go alone at first, get a steady job, find proper housing and accumulate savings before asking their families to follow them.

17

,

39

,

40

Other books

Asimov's Science Fiction: October/November 2013 by Penny Publications

Ember of a New World by Watson, Tom

Whisper To Me In The Dark by Claire, Audra

Through Time-Whiplash by Conn, Claudy

Night Beat by Mikal Gilmore

Holding a Tender Heart by Jerry S. Eicher

Around the Way Girls 9 by Moore, Ms. Michel

Saved: A Billionaire Romance (The Saved Series Book 1) by Lexi Larue