The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan (32 page)

Read The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan Online

Authors: Michael Hastings

“You have to keep up,” Duncan told me. “We move very, very fast.”

We went into the Yellow House, the main building on the base where I had last interviewed General McKiernan in October 2008. A third Macedonian sat at a large wooden desk in the building’s lobby. I had to trade in my first visitor badge for a second visitor badge to enter. There was a sign on the wall warning soldiers to drive safely—reckless driving, the sign warned, didn’t win the love of the Afghan people.

The plan for the day: I would sit in on the morning briefing, and then I would travel with McChrystal to Kandahar. In Kandahar, we would split up—McChrystal and Flynn would visit a Special Forces detachment somewhere in the south while Duncan and I would meet up with Task

Force 1-12, the infantry unit that McChrystal had gone on patrol with in February. I’d read parts of the e-mails that kid named Staff Sergeant Israel Arroyo had sent. I wanted to interview him if I had the chance.

Duncan sat me down to wait in the operations center. The briefing would start at 0730. Whiteboards lined the wall, scribbled with notes about McChrystal’s travel plans. Next to a whiteboard were a few pages printed out of Bruce Lee quotes.

McChrystal’s team included a Bruce Lee quote on almost all the daily schedules they printed out. Some of the quotes up on the wall were crossed out—they’d been used already.

I scanned the quotes. There were fifteen listed, some marked as used, with a date next to them.

A goal is not always meant to be reached; it often serves as something to aim at. Used 4/11

A quick temper will make a fool of you soon enough.

A wise man can learn more from a foolish question than a fool can learn from a wise answer.

Always be yourself. Express yourself, have faith in yourself. Do not go out for a successful personality and duplicate it.

I’m not in this world to live up to your expectations, and you’re not in this world to live up to mine.

The philosopher warrior. It was an image McChrystal’s team cultivated. His men liked to think there was something of Bruce Lee in McChrystal—lean, wise, and deadly.

I drank a cup of coffee.

Duncan popped back into the room to get me for the briefing.

I walked into the situational awareness room, or SAR. I wasn’t allowed to record the briefing, but I could take notes on background, he explained. I’d sit in on two briefings over the next week, and this is what I saw and heard.

The room was the cerebral cortex for the war. There were ten television monitors set up across the front of the room, a podium, and three rows of tables with workstations and phones. There was a third row of chairs against the wall. The screens broadcast live updates about the war, distilled down to color-coded data, all the violence broken down in up-to-the-hour statistical analysis. Casualties over the past twenty-four hours were on one screen: yellow for Coalition troops, blue for Afghan security forces, and red for civilians who were killed or injured. Another screen carried information about the latest security incidents: an IED in Kandahar, a political assassination in Jalalabad, serious reporting inaccuracies in ANA recordkeeping, Iran providing an unknown antiaircraft weapon to Helmand. Two more screens had on television news broadcasts, Al Jazeera and CNN. (McChrystal had banned Fox News from the TV screens because of its political slant.) About forty military officers crowded into the room, while across Afghanistan three thousand more officers and enlisted personnel in their own headquarters linked in to watch the briefing. I was the only journalist there.

The briefers went up to the podium, one after the other. A deputy head of the Special Forces command updated McChrystal on the latest operations. He talked about the “jackpots” from last night—the code word given for the killing or capturing of a high-profile target. They had a mission called Operation Euphoria in Spin Boldak. A briefer from the CIA stood up and gave his intelligence update—the latest intel said the Taliban were claiming “they want to shut down Highway One, and they’re going to start attacking civilian convoys.” He gave a little talk about how all the players in the region were jamming everyone’s cell phone signals—the Taliban would shut the network down at night while the “Chinese are jamming illegally, and the Paks are jamming the Chinese.” Other major commands across the country got their chance to brief through the video uplink, including a screen beaming back to the Pentagon a lone man sitting at a desk in the bowels of the building, where it was almost midnight.

An officer gave an update on a reconstruction project in Spin Boldak. Another talked about seventeen checkpoints in Wardak province that the Afghan army and police were taking over. Most of the room seemed to have tuned out at this point. McChrystal wanted to know where the exact coordinates for the checkpoints were.

“Let’s ask that question now,” McChrystal said.

“Uh, not sure what the question is,” the officer replied.

“Pay attention, please,” McChrystal reprimanded. The officer fumbled around over the video uplink. “Uh, okay, I can send up the grid coordinates.”

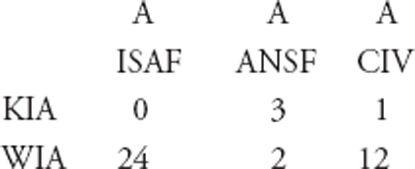

They moved on to the Casualty Events Update. There had been seven in the last twenty-four hours. The chart broke down like this:

“There was a, uh, fifty cal through the windshield,” one officer told McChrystal, talking about an incident that wounded an American soldier. McChrystal nodded, taking a sip of coffee from his Styrofoam cup.

Another slide noted the 310 percent increase in Coalition casualties. The briefer attributed the rise in violence to “COIN and the surge.”

The officer reported on the latest numbers of IED (improvised explosive device) attacks. The IEDs were bombs, often made out of fertilizer, old munitions, and wood. In Iraq, the Pentagon had spent billions on figuring out how to stop them from detonating, using fourteen different advanced systems to interfere with the remote-controlled detonation device. In Afghanistan, the insurgents had figured out a way around the jammers: to go so low-tech that American technology wouldn’t help. The most popular method was called a pressure plate, which resembled the trigger mechanism on an old-fashioned landmine. The bombs were

getting even bigger, the average size being close to forty pounds. IEDs were responsible for more than 60 percent of American casualties, and the data predicted that by the end of 2010 approximately eighteen thousand IEDs would be set in Afghanistan, a “vast increase in IED activity,” the briefer noted.

McChrystal nodded. “It’s a sobering number, to be sure,” he said. “This data shows we have a rising challenge here. We have to avoid and defeat IEDs. We need to be more agile, less sluggish.”

The rest of the briefings included an update on regional affairs (Mumbai attack conviction: Message to Islamabad Not to Export Terrorism) and other key events (Reports of Assassination in Kunduz) and a discussion about a new award the military was considering handing out for “Courageous Restraint.” It was an award to soldiers for not shooting at civilians who they mistakenly believed posed a threat. The idea was to incentivize the new rules of engagement McChrystal had issued, though the general wasn’t quite sold on the idea.

“We ask courage of them every day,” he said. Whether or not they should get an award for it was a “philosophical question,” McChrystal said.

The briefing that morning concluded. Duncan came up beside me.

“We move very, very fast,” he said again.

McChrystal and his entourage burst out the door of the headquarters, a convoy of black sport-utility vehicles, heavily armored Suburbans, idled. I jumped in one SUV—in it were a pair of nunchuks.

The nunchuks had been custom-made for McChrystal. On one handle, it said the general’s name; on the other, there were four stars. It started as a joke, continuing the Bruce Lee theme: A few months earlier, McChrystal had been going through his checklist with an aide. You have my briefing book? Check. My backpack? Check. My glasses? Check. Nunchuks? McChrystal had said.

The joke stuck.

The convoy rolled across the street to a nearby helicopter landing field. We jumped out; the helicopters arrived; we jumped in the helicopters; the helicopters swooped up, flying low over the city, back out to the military side of the Kabul Airport. We jumped out of the helicopters; two jets were waiting for us. Ocean 11 and Ocean 12. We ran across the tarmac and up into the private jet.

Nunchuks

The jet had the look of the typical plane for an executive. It had dark blue leather seats and three coffee tables, with plastic cups embossed with the United States government seal. The main difference was the luggage: The seats were stacked with radio equipment, rucksacks, and body armor.

McChrystal walked on the plane and looked around. He bumped into his chief security officer and personal bodyguard, who everyone called Chief. Chief was responsible for getting the nunchuks and the nunchuks holder made.

Nunchuks holder

“You’re the same guys I went to the gym this morning with,” McChrystal said.

“Yes, sir,” Chief answered.

“Everywhere I go, I keep seeing the same people,” he said.

McChrystal sat down in the front of the plane.

“It’s him surrounding my world,” Chief said.

“I must be cloning myself,” McChrystal shot back.

This was going to be my last sit-down interview with General McChrystal. Duncan called me up to the front of the plane. I took out my tape recorder and sat across from the general. We started talking as the plane took off. I set my coffee in the cup holder on the fake wood paneling, watching it spill as the jet shot upward.

McChrystal described the war in Afghanistan as “raising a child.” It would be messy, and you only had so much control over the outcome. “You might want them to be a rock star, or a heavyweight wrestler or whatever, but at the end of the day, you have to provide the environment, and they have to be what’s best for them.”

He told me his biggest fear wasn’t physical—it was letting down the people who had put faith in him. “They’ve made a big bet on me,” he said. I asked him about the Special Forces missions he went on in Iraq. Did any stand out as particularly crazy? “The funniest,” he said, “though not all of them were funny.” He went out on a mission in 2006 when Baghdad was “pretty grim.” When the Special Forces team entered the house, a fire started. They yelled out the code word

Lancelot

—which meant the house was wired to detonate, something they’d seen before. “That’s when, if you’re a Monty Python fan, that’s the runaway call. ‘Runaway!’ We ran for the appropriate distance, then at the end we felt like Monty Python characters. I just ran away from the objective. How do I recover my dignity?” he laughed.