The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (23 page)

butter in ice, high silver coffee-pot,

and, heaped, on a salver, the morning’s post.

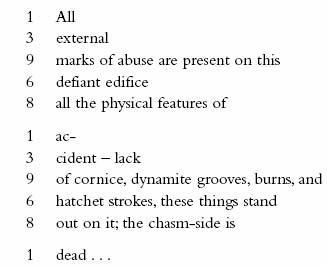

Note that ‘porcelain’ in true upper-class British would have to be pronounced ‘porslin’ to make the count work. Some kind of form is offered by the rhyming–one feels otherwise that the heavily run-on lines would be in danger of dissolving the work into prose. It was Daryush’s exact contemporary the American poet Marianne Moore (1887–1969) who fully developed the manner. Her style of scrupulous, visually arresting syllabic verse has been highly influential. Here is an extract from her poem ‘The Fish’ with its syllable count of 1,3,9,6,8 per stanza.

As you can see, the count is important enough to sever words in something much fiercer than a usual enjambment. The apparent randomness is held in check by delicate rhyming:

this/edifice

,

and/stand

.

‘I repudiate syllabic verse’ Moore herself sniffed to her editor and went further in interview:

I do not know what syllabic verse is, can find no appropriate application for it. To be more precise, to raise to the status of science a mere counting of syllables seems to me frivolous.

As Dr Peter Wilson of London Metropolitan University has pointed out, ‘…since it is clear that many of her finest poems could not have been written in the form they were without the counting of syllables, this comment is somewhat disingenuous.’ Other poets who have used syllabics include Dylan Thomas, Thom Gunn and Donald Justice, this from the latter’s ‘The Tourist from Syracuse’:

You would not recognize me.

Mine is the face which blooms in

The dank mirrors of washrooms

As you grope for the light switch.

Between the Daryush and the Moore I hope you can see that there are possibilities in this verse mode. There is form, there is shape. If you like the looser, almost prose-poem approach, then writing in syllabics allows you the best of both worlds: structure to help organise thoughts and feelings into verse, and freedom from what some poets regard as the jackboot march of metrical feet. The beauty of such structures is that they are self-imposed, they are not handed down by our poetic forebears. That is their beauty but also their terror. When writing syllabics you are on your own.

It

must

be time for another exercise.

Poetry Exercise 8

- Two stanzas of alternating seven-and five-line syllabic verse: subject

Rain

. - Two stanzas of verse running 3, 6, 1, 4, 8, 4, 1, 6, 3: subject

Hygiene

.

Here are my attempts, vague rhymes in the first, some in the second: you don’t have to:

Rain

they say there’s a taste before

it comes; a tin tang

like tonguing a battery

or a cola can

I know that I can’t smell it

but the animals

glumly lowering their heads

can foretell its fall:

they can remember rains past

as I come closer

their eyewhites flash in fear of

another Noah

Hygiene

I’m filth

On the outside I stink.

But,

There are people

So cleansed of dirt it makes you think

Unhygienic

Thoughts

Of them. I’d much rather

Stay filthy.

Their lather

Can’t reach where they reek,

Suds

Can’t soap inside.

All hosed, scrubbed and oilily sleek

They’re still deep dyed

They

Can stand all day and drench

They still stench.

We have come to the end of our chapter on metrical modes. It is by no means complete. If you were (heaven forbid) to go no further with my book, I believe you would already be a much stronger and more confident poet for having read thus far. But please don’t leave yet, there is much to discover in the next chapters on rhyming and on verse forms: that is where the fun really begins. Firstly, a final little exercise awaits.

Poetry Exercise 9

Coleridge wrote the following verse in 1806 to teach his son Derwent the most commonly used metrical feet. Note that he uses the classical ‘long’ ‘short’ appellation where we would now say ‘stressed’ ‘weak’. For your final exercise in this chapter,

WHIP OUT YOUR PENCIL

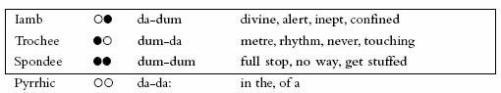

and see how in the first stanza he has suited the metre to the description by scanning each line. By all means refer to the ‘Table of Metric Feet’ below. You are not expected to have learned anything off by heart. I have included the second stanza, which does not contain variations of metre, simply because it is so touching in its fatherly affection.

Lesson for a Boy

Trochee trips from long to short;

From long to long in solemn sort

Slow Spondee stalks, strong foot!, yet ill able

Ever to come up with Dactyl's trisyllable.

Iambics march from short to long;–

With a leap and a bound the swift Anapaests throng;

One syllable long, with one short at each side,

Amphibrachys hastes with a stately stride;–

First and last being long, middle short, Amphimacer

Strikes his thundering hoofs like a proud high-bred Racer.

If Derwent be innocent, steady, and wise,

And delight in the things of earth, water, and skies;

Tender warmth at his heart, with these metres to show it,

With sound sense in his brains, may make Derwent a poet,

May crown him with fame, and must win him the love

Of his father on earth and his Father above.

My dear, dear child!

Could you stand upon Skiddaw, you would not from its whole ridge

See a man who so loves you as your fond S.T. Coleridge…

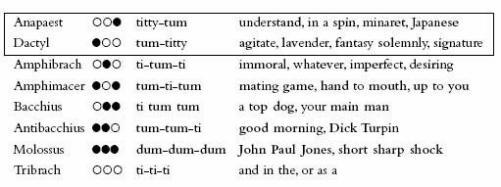

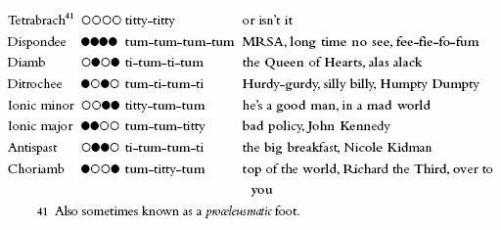

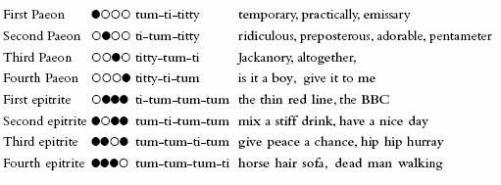

Table of Metric Feet

B

INARY

T

ERNARY

Q

UATERNARY

Q

UATERNARY

continued

Now about the metrics: the terminology you use–of amphibrachs, pyrrhics etc.–is obsolete in English. We now speak of these feet only in analyzing choruses from Greek plays–because Greek verse is quantitative […] we have simplified our metrics to five kinds of feet […] trochee, iambus, anapest, dactyl, spondee. We do not need any more.

Edmund Wilson in a letter to Vladimir Nabokov, 1 September 1942

CHAPTER TWO

Rhyme

It is the one chord we have added to the Greek lyre.

O

SCAR

W

ILDE:

‘The Critic as Artist’

I

Rhyme, a few general thoughts

‘Do you rhyme?’

This is often the first question a poet is asked. Despite the absence of rhyme in Greece and Rome (hence Wilde’s aphorism above), despite the glories of Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Tennyson and all the blank-verse masterpieces of English literature from the Dark Ages to the present day, despite a hundred years of Modernism, rhyming remains for many an almost defining feature of poetry. It ain’t worth a dime if it don’t got that rhyme is how some poets and poetry lovers would sum it up. For others rhyming is formulaic, commonplace and conventional: a feeble badge of predictability, symmetry and bourgeois obedience.

There are very few poets I can call to mind who

only

used rhyme in their work, but I cannot think of a single one, no matter how free form and experimental, who

never

rhymed. Walt Whitman, Ezra Pound, D. H. Lawrence, Wyndham Lewis, William Carlos Williams, T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, e e cummings, Crane, Corso, Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg, Hughes–not an exception do I know.

There are some stanzaic forms, as we shall find in the next chapter, which seem limp and unfinished without the comfort and assurance that rhyme can bring, especially ballads and other forms that derive from, or tend towards, song. In other modes the verse can seem cheapened by rhyme. It is hard to imagine a rhyming version of Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’ or Eliot’s

Four Quartets

, for example. This may of course be a failure of imagination: once a thing is made and done it is hard to picture it made and done in any other way.

The question ‘to rhyme or not to rhyme’ is not one I can answer for you, except to say that it would almost certainly be wrong to answer it with ‘always’ or ‘never’.

Rhyme, like alliteration (which is sometimes called

head rhyme

) is thought to have originated in pre-literate times as a way of allowing the words of sung odes, lyrics, epics and sagas more easily to be memorised. Whatever its origin, the expectations it sets up in the mind seem deeply embedded in us. Much of poetry is about ‘consonance’ in the sense of

correspondence

: the likeness or congruity of one apparently disparate thing to another. Poetry is concerned with the connections between things, seeing the world in a grain of sand as Blake did in ‘Auguries of Innocence’, or sensing loss of faith in the ebbing of the tide as Arnold did in ‘Dover Beach’. You might say poets are always looking for the wider

rhymes

in nature and experience. The Sea ‘rhymes’ with Time in its relentless flow, its eroding power, its unknowable depth. Hope ‘rhymes’ with Spring, Death ‘rhymes’ with Winter. At the level of physical observation, Blood ‘rhymes’ with Wine, Eyes with Sapphires, Lips with Roses, War with Storms and so on. Those are all stock correspondences which were considered clichés even by Shakespeare’s day of course, but the point is this: as pattern-seeking, connection-hungry beings we are always looking for ways in which one thing chimes with another. Metonym, metaphor and simile do this in one way, rhyme, the apparently arbitrary chiming of word sounds, does it in another. Rhyme, as children quickly realise, provides a special kind of satisfaction. It can make us feel, for the space of a poem, that the world is less contingent, less random, more connected, link by link. When used well rhyme can

reify

meaning, it can embody in sound and sight the connections that poets try to make with their wider images and ideas. The Scottish poet and musician Don Paterson puts it this way:

Rhyme always unifies sense […] it can trick a logic from the shadows where one would not otherwise have existed.

An understanding of rhyme comes to us early in life. One sure way to make young children laugh is to deny them the natural satisfaction of expected end-rhymes, as in this limerick by W. S. Gilbert:

There was an old man of St Bees

Who was horribly stung by a wasp

When they said: ‘Does it hurt?’

He replied: ‘No it doesn’t–

It’s a good job it wasn’t a hornet.’

We all know of people who are tone-deaf, colour-blind, dyslexic or have no sense of rhythm, smell or taste, but I have never heard of anyone who cannot distinguish and understand rhyme. There may be those who genuinely think that ‘bounce’ rhymes with ‘freak’, but I doubt it. I think we can safely say rhyme is understood by all who have language. All except those who were born without hearing of course, for rhyming is principally a question of

sound

.

The Basic Categories of Rhyme

End-rhyme

s–

internal rhymes

While it is possible that before you opened this book you were not too sure about metre, I have no doubt that you have known since childhood exactly what rhyme is. The first poems we meet in life are nursery

rhymes

.

Humpty Dumpty sat on the

wall

Humpty Dumpty had a great

fall

All the King’s horses and all the King’s

men

Couldn’t put Humpty together

again.

That famous and deeply tragic four-line verse (or

quatrain

) consists of two

rhyming couplets

. Here is an example of a ballady kind of quatrain where only the three-stress (second and fourth) lines bear the rhyme words:

Mary had a little lamb

Its fleece was white as

snow

And everywhere that Mary went

The lamb was sure to

go

.

In both examples, the rhyme words come at the end of the line:

fall/wall, men/again, snow/go

. This is called

END RHYMING

.

Little Bo

Peep

has lost her

sheep

And doesn’t know where to

find them

.

Leave them

alone

and they’ll come

home

,

Bringing their tails be

hind them

.

Little Bo

Peep

fell fast

asleep

And dreamt she heard them

bleating

But when she

awoke

she found it a

joke

For they were still

afleeting

.

Here we have end-rhymes as before but

INTERNAL RHYMES

too, in the four-beat lines:

Peep/sheep, alone/home, Peep/asleep

and

awoke/joke

. Coleridge used this kind of internal rhyming a great deal in his ‘Ancient Mariner’:

The fair breeze

blew

, the white foam

flew

,

The furrow followed

free

:

We were the

first

that ever

burst

Into that silent

sea

.

As did Lewis Caroll in ‘The Jabberwocky’:

He left it

dead

, and with its

head

He went galumphing back.

A rarer form of internal rhyming is the leonine which derives from medieval Latin verse.

1

This is found in poems of longer measure where the stressed syllable preceding a caesura rhymes with the last stressed syllable of the line. Tennyson experimented with leonine rhymes in his juvenilia as well as using it in his later poem ‘The Revenge’:

And the stately Spanish

men

to their flagship bore him

then

,

Where they laid him by the

mast

, old Sir Richard caught at

last

,

And they praised him to his

face

with their courtly foreign

grace

.

I suppose the internal rhyming in ‘The Raven’ might be considered leonine too, though corvine would be more appropriate…

But the raven, sitting

lonely

on that placid bust, spoke

only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did

outpour

.

Nothing further then he

uttered

; not a feather then he

fluttered

;

Till I scarcely more than

muttered

, ‘Other friends have flown

before

;

On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown

before

.’

Then the bird said, ‘

Nevermore

.’

Throughout the poem Poe runs a third internal rhyme (here

uttered/fluttered

) into the next line (

muttered

).

Hopkins employed internal rhyme a great deal, but not in such predictable patterns. He used it to yoke together the stresses in such phrases as

dapple-dawn-drawn, stirred for a bird, he cursed at first, fall gall, in a flash at a trumpet-crash, glean-stream

and so on.

Partial Rhymes

Partial rhymes: assonance and consonance–eye-rhyme and wrenched rhyme

On closer inspection that last internal rhyme from Hopkins is not quite right, is it?

Glean

and

stream

do not share the same final consonant. In the third line of ‘Little Bo Beep’ the

alone/home

rhyme is imperfect in the same way: this is

PARTIAL RHYME

, sometimes called

SLANT

-rhyme or

PARA-RHYME

.

2

In slant-rhyme of the

alone/home, glean/stream

kind, where the vowels match but the consonants do not, the effect is called

ASSONANCE

: as in

cup/rub, beat/feed, sob/top, craft/mast

and so on. Hopkins uses

plough/down, rose/moles, breath/bread, martyr/master

and many others in

internal

rhymes, but never as end-rhyme. Assonance in end-rhymes is most commonly found in folk ballads, nursery rhymes and other song lyrics, although it was frowned upon (as were all partial rhymes) in Tin Pan Alley and musical theatre. On Broadway it is still considered bad style for a lyricist not to rhyme perfectly. Not so in the world of pop: do you remember the Kim Carnes song ‘Bette Davis Eyes’? How’s this for assonance?

She’s fer

ocious

And she

knows just

What it takes to make a

pro blush

Yowser! In the sixties the Liverpool School of poets, who were culturally (and indeed personally, through ties of friendship) connected to the Liverpool Sound, were notably fond of assonantal rhyme. Adrian Mitchell, for example, rhymes

size

with

five

in his poem ‘Fifteen Million Plastic Bags’. The poets you are most likely to find using assonantal slant-rhymes today work in hip-hop and reggae traditions: Here’s ‘Talking Turkey’ by Benjamin Zephaniah. Have fun reading it out à la B.Z.–

Be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas

Cos’ turkeys just wanna hav fun

Turkeys are cool, turkeys are wicked

An every turkey has a Mum.

Be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas,

Don’t eat it, keep it alive,

It could be yu mate, an not on your plate

Say, ‘Yo! Turkey I’m on your side.’

I got lots of friends who are turkeys

An all of dem fear christmas time,

Dey wanna enjoy it,

dey say humans destroyed it

n humans are out of dere mind,

Yeah, I got lots of friends who are turkeys

Dey all hav a right to a life,

Not to be caged up an genetically made up

By any farmer an his wife.

You can see that

fun/Mum, alive/side, time/mind, enjoy it/destroyed it

and perhaps

Christmas/wicked

are all used as rhyming pairs. The final pair

life/wife

constitute the only ‘true’ rhymes in the poem. Assonantally rhymed poems usually do end best with a full rhyme.

Now let us look at another well-known nursery rhyme:

Hickory, dickory,

dock

,

The mouse ran up the

clock

.

The clock struck

one

,

The mouse ran

down

!

Hickory, dickory,

dock

.

The

one/down

rhyme is partial too, but here the end consonant is the same but the

vowels

(vowel

sounds

) are different. This is called

CONSONANCE

: examples would be

off/if, plum/calm, mound/bond

and so on. Take a look at Philip Larkin’s ‘Toads’:

Why should I let the toad

work