The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (19 page)

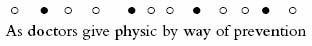

And this of ‘From my own Monument’:

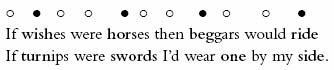

You might think amphibrachs (with the weak ending docked) lurk in this old rhyming proverb:

But that’s just plain silly:

27

it is actually more like the metre of Browning’s ‘Ghent to Aix’: anapaests with the opening syllable docked.

If

wish

es were

hors

es then

beg

gars would

ride

I

sprang

to the

sad

dle and

Jor

is and

he

.

Just as

my

amphibrachic doggerel could be called a clipped anapaestic line with a weak ending:

Ro

man

tic, de

lud

ed, a

tot

al dis

ast

er.

Don’t

do

it I

beg

you, self-

slaught

er is

fast

er

Some metrists claim the amphibrach

can

be found in English poetry. You will see it and hear it in perhaps the most popular of all verse forms extant, they say. I wonder if you can tell what this form is, just by

READING OUT THE RHYTHM

?

Ti-

tum

-ti ti-

tum

-ti ti-

tum

-ti

Ti-

tum

-ti ti-

tum

-ti ti-

tum

-ti

Ti-

tum

-ti ti-

tum

Ti-

tum

-ti ti-

tum

Ti-

tum

-ti ti-

tum

-ti ti-

tum

-ti

It is, of course, the limerick.

There was a young man from Australia

Who painted his arse like a dahlia.

Just tuppence a smell

Was all very well,

But fourpence a lick was a failure.

So, next time someone tells you a limerick you can inform them that it is verse made up of three lines of amphibrachic trimeter with two internal lines of catalectic amphibrachic dimeter. You would be punched very hard in the face for pointing this out, but you could do it. Anyway, the whole thing falls down if your limerick involves a monosyllabic hero:

There was a young chaplain from King’s,

Who discoursed about God and such things:

But his deepest desire

Was a boy in the choir

With a bottom like jelly on springs.

Ti-

tum

titty-

tum

titty-

tum

Titty-

tum

titty-

tum

titty-

tum

Titty-

tum

titty-

tum

Titty-

tum

titty-

tum

Titty-

tum

titty-

tum

titty-

tum

You don’t get much more anapaestic than that. A pederastic anapaestic quintain,

28

28

in fact. Most people would say that limericks are certainly anapaestic in nature and that amphibrachs belong only in classical quantitative verse. Most people, for once, would be right. The trouble is, if you vary an amphibrachic line even slightly (which you’d certainly want to do whether it was limerick or any other kind of poem), the metre then becomes impossible to distinguish from any anapaestic or dactylic metre or a mixture of all the feet we’ve already come to know and love. Simpler in verse of triple feet to talk only of rising three-stress rhythms (anapaests) and falling three-stress rhythms (dactyls). But by all means try writing with amphibrachs as an exercise to help flex your metric muscles, much as a piano student rattles out arpeggios or a golfer practises approach shots.

T

HE

A

MPHIMACER

It follows that if there is a name for a three-syllable foot with the beat in the middle (ro

mant

ic, des

pond

ent, un

yield

ing) there will be a name for a three-syllable foot with a beat either side of an

un

stressed middle (

tamp

er

proof, hand

to

mouth, Ox

ford

Road

).

29

Sure enough: the

amphimacer

(

macro

, or long, on both sides) also known as the

cretic foot

(after the Cretan poet Thaletas) goes

tum

-ti-

tum

in answer to the amphibrach’s ti-

tum

-ti. Tennyson’s ‘The Oak’, which is short enough to reproduce here in full, is written in amphimacers and is also an example of that rare breed, a poem written in monometer, lines of just one foot. It could also be regarded as a

pattern

or

shaped

poem (of which more later) inasmuch as its layout suggests its subject, an oak tree.

Live thy life,

Young and old,

Like yon oak,

Bright in spring,

Living gold;

Summer-rich

Then; and then

Autumn-changed,

Soberer hued

Gold again.

All his leaves

Fall’n at length,

Look, he stands,

Trunk and bough,

Naked strength.

Alexander Pope a century earlier had written something similar as a tribute to his friend Jonathan Swift’s

Gulliver’s Travels

:

In amaze

Lost I gaze

Can our eyes

Reach thy size?

…and so on. Tennyson’s is more successful, I think. You won’t find too many other amphimacers on your poetic travels: once again, English poets, prosodists and metrists don’t really believe in them. Maybe you will be the one to change their minds.

Q

UATERNARY

F

EET

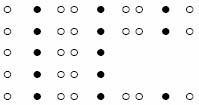

Can one have metrical units of four syllables? Quaternary feet? Well, in classical poetry they certainly existed, but in English verse they are scarce indeed. Suppose we wrote this:

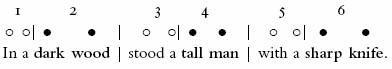

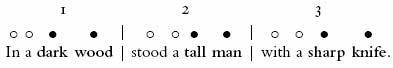

That’s a hexameter of alternating pyrrhic and spondaic feet and might make a variant closing or opening line to a verse, but would be hard to keep up for a whole poem. However, you could look at it as a

trimeter

:

The name for this titty-

tum-tum

foot is a

double iamb

, sometimes called an

ionic minor

. Again, these are incredibly rare in English poetry. One such foot might be used for emphasis, variation or the capturing of a specific speech pattern, but it is never going to form the metrical pattern for a whole poem, save for the purposes of a prosodic equivalent of a Chopin étude, in other words as a kind of training exercise. Whether you call the above line an ionic minor or double iambic trimeter, a pyrrhic spondaic hexameter or any other damned thing really doesn’t matter. Rather insanely there is a quaternary foot called a

diamb

, which goes ti-

tum

-ti

tum

, but for our purposes that is not a foot of four, it is simply two standard iambic feet. Frankly my dear, I don’t give a diamb. Some people, including a couple of modern practising poets I have come across, like the double iamb, however, and would argue that the Wilfred Owen line I scanned as a pyrrhic earlier:

Should properly be called a double iamb or ionic minor since ‘good-bye’ is double-stressed: