The Norman Conquest (24 page)

Read The Norman Conquest Online

Authors: Marc Morris

How Harold might have realized his ambition had the northern rebellion not happened, or been unsuccessful, is anybody’s guess. But it is far from certain that, had Tostig remained in power as earl of Northumbria at the time of Edward’s death, he would have stood in the way of his brother’s accession. The rivalry between Tostig and Harold was a consequence of the October rising, not a cause of it. Indeed, if we look back at their careers before that point, all we can see is co-operation – Tostig’s support of Harold’s conquest of Wales being the most obvious case in point. Part of the reason for the Godwine family’s success had always been their ability to stick together in both triumph and adversity. Based on past behaviour, it is more reasonable to suppose that Tostig, had he not been banished, would have supported rather than opposed his older brother’s bid for the throne.

The real obstacle to Harold’s ambition was neither Tostig nor William but Edgar Ætheling. The son of Edward the Exile, great-nephew of Edward the Confessor, Edgar was directly descended from the ancient dynasty that had ruled Wessex, and later England, since the beginning; the blood of Alfred and Athelstan, not to mention the celebrated tenth-century King Edgar, flowed in his veins. This fact, combined with the considerable efforts that had been required to secure his return from Hungary, must have led many to expect that the ætheling would in due course succeed his great-uncle. After all, his title, accorded to him in contemporary sources, indicates that he was considered worthy of ascending the throne. Moreover, according to one Continental chronicler with close connections to the English court, Harold himself had sworn to the Confessor that, when the time came, he would uphold Edgar’s cause.

13

Whether this was true or not, the mere existence of this legitimate heir was singularly awkward for Harold. The saving grace was that in the autumn of 1065 Edgar was little more than a child, apparently no more than thirteen years old, and – owing to the Confessor’s political weakness – with no power base of his own.

14

All Harold needed was enough of the other English magnates to agree that Edgar’s rights should be set aside, which is what he must have obtained

from Eadwine and Morcar. The incentive for them, of course, was Harold’s marriage to their sister. As queen, Ealdgyth would produce children who would unite the fortunes of the two formerly rival houses, and a new royal dynasty would arise to take the place of the old.

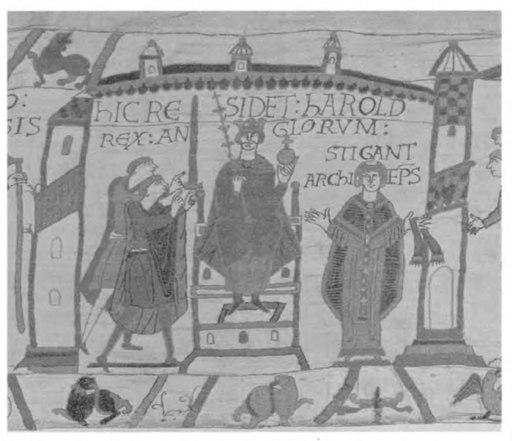

No single fact points to a conspiracy of this kind more obviously than the circumstances of Harold’s coronation, which took place on 6 January 1066, probably in Westminster Abbey. The Bayeux Tapestry shows the new king crowned and enthroned, holding his rod and sceptre, flanked on one side by two men who hand him a ceremonial sword, and on the other by the solitary figure of Archbishop Stigand. The inclusion of the excommunicate archbishop of Canterbury is almost certainly an underhand piece of Norman propaganda: it is far more likely that Harold’s consecration was performed by Ealdred, the archbishop of York, as John of Worcester later insisted was the case. What

does

damn Harold, however, is the unseemly haste with which the ceremony was arranged. The new king was crowned the day after the Confessor’s death, and on the same day as the old king’s funeral. No previous king of England had demonstrated such a desperate hurry to have himself consecrated, for the good reason that in England the coronation had never been regarded as a constitutive part of the king-making process. Normally many months would pass between the crucial process of election and a new ruler’s formal investiture. Edward the Confessor, as we have seen, had come to the throne by popular consent in the summer of 1042, but was not crowned until Easter the following year. Harold’s rush to have himself crowned within hours of his predecessor’s death was therefore quite unprecedented, and suggests that he was trying to buttress what was by any reckoning a highly dubious claim with an instant consecration. It is the most obviously suspect act in the drama.

15

The last weeks of 1065, then, probably ran as follows. The king is clearly dying, and the greatest earl in the kingdom determines he will succeed him, having perhaps nurtured the hope of doing so for several years. He strikes a deal with his rivals in exchange for their support. The king dies, inevitably behind closed doors, and surrounded by only a handful of intimates, including the earl himself, his sister the queen and a partisan archbishop of Canterbury; afterwards it is given out that the old king, in his dying moments, nominated the earl as his successor. Before anyone can object – indeed, so fast that the dead king is barely in his grave – the new king is crowned, and is therefore deemed to be God’s anointed.

Not everyone was convinced. Clearly many people were surprised by Harold’s succession, not least because it required a far more legitimate candidate – Edgar Ætheling – be set aside. Half a century later, the historian William of Malmesbury wrote that Harold had seized the throne, having first exacted an oath of loyalty from the chief nobles. Malmesbury was hardly a hostile witness: in the same paragraph he praises Harold as a man of prudence and fortitude, and notes the English claim that the earl was granted the throne by Edward the Confessor. ‘But I think’, he adds, ‘that this claim rests more on goodwill than judgement, for it makes [the Confessor] pass on his inheritance to a man of whose influence he had always been suspicious.’

16

More telling still is an account written in the 1090s for Baldwin, abbot of Bury St Edmunds, which described Harold’s hasty coronation as sacrilegious,

and accused the earl of taking the throne ‘with cunning force’. Since Baldwin had formerly been Edward the Confessor’s physician, and was therefore very likely present at his death, this testimony ought to be accorded considerable weight. It is also possible that there was opposition in the north of England at the unexpected enthronement of the earl of Wessex. We know that soon after his coronation Harold travelled to York, a destination far beyond the usual ambit of English kings. Perhaps the occasion was his marriage to Ealdgyth, planned secretly in advance and now publicly celebrated. Alternatively, Harold may have had to go there in order to quell opposition to his rule. William of Malmesbury says as much, and has it that the people of Northumbria initially refused to accept Harold as their king. Unfortunately, elements of his story suggest that he may have confused these events with the northern rebellion of the previous year. Nevertheless, the likeliest reason for Harold’s trip to York was some sort of unrest. As the C version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle ruefully observed, there was little quiet in England while Harold wore the crown.

17

Sadly we have few good contemporary sources for the immediate reaction in Normandy to the news of Harold’s accession. The chronicler Wace, writing a century later, says that William was near Rouen, preparing to go hunting with his knights and squires, when a messenger arrived from England. The duke heard the message privately, and then returned to his hall in the city in anger, speaking to no one.

18

Whatever the merits of this scene, we can surmise certain things. Edward the Confessor’s final illness had been quite long-drawn-out, and so William must have known in the closing weeks of 1065 that the English throne was about to fall vacant. This has led some historians to wonder why he did not cross the Channel earlier, perhaps in time for Christmas, in order to push his candidacy when the moment arrived. In reality, though, this was not an option. If William had come in anticipation, however large an escort he might have been allowed to bring, he would still have been a stranger in a strange land, ill-placed to resist any parties that opposed his accession, and, moreover, vulnerable to the sort of deadly intrigues that went on at the English court. The only realistic option for William was to do precisely as he did: remain in Normandy and await an invitation to come and be crowned,

as had previously happened in the case of Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor. More to the point, he already had someone who was supposed to be representing his interests in England, namely Harold Godwineson. During his trip to Normandy, says William of Poitiers, Harold had promised William ‘that he would strive to the utmost with his counsel and with his wealth to ensure that the English monarchy should be pledged to him after Edward’s death’. The news that Harold had made himself king was thus regarded by William as a betrayal, a violation of the fealty and the other sacred oaths he had previously sworn. According to William of Jumièges, the duke’s immediate response was to send messengers to England urging Harold to renounce the throne and keep his pledges. Harold, unsurprisingly, chose to ignore these admonitions.

19

From an early stage, therefore, it must have been clear that if William was going to obtain the English throne, he would have to mount an invasion of England – ‘to claim his inheritance through force of arms’, as William of Poitiers put it. Needless to say, this was an incredibly risky proposition, quite unlike the cautious kind of warfare that he had practised to such advantage during the previous two decades. Its only real parallel – in terms of risk rather than scale – is the battle he chose to fight at the start of his career, at Val-ès-Dunes, when threatened with extinction by his domestic enemies. From this we can reasonably conclude that Norman writers who emphasize the justice of William’s cause – in particular his chaplain, William of Poitiers – accurately reflected the attitude of the duke himself. By choosing to embark upon a strategy of direct confrontation, William was effectively submitting that cause – along with his reputation, his life and the lives of thousands of fellow Normans – to the judgement of God.

20

The duke’s conviction in the righteousness of his cause is also reflected in his appeal to the pope. Very soon after learning of Harold’s accession, he dispatched an embassy to Rome to put his case before Alexander II. Sadly, no text of this case survives, but there is no doubt that it was written down and circulated widely at the time, for it seems to inform several of the Norman accounts of 1066 (that of William of Poitiers in particular). Edward’s promise and Harold’s perjury were evidently the main planks of its argument,

though it is likely that the Normans also alleged laxity against the English Church, epitomized by Archbishop Stigand. The pope clearly felt that the case was well founded (it may also have helped that he was a former pupil of Lanfranc), for he quickly decided that force would be legitimate. As a token of his decision, he sent William’s ambassadors back from Rome bearing a banner that the duke could carry into battle.

21

The support of the pope was all well and good, but what of support in Normandy itself? Another of William’s initial moves in 1066 was evidently to summon a select meeting of the duchy’s leading men: his half-brothers Robert and Odo and his friends William fitz Osbern and Roger of Montgomery are among the familiar names mentioned by Wace and William of Poitiers. According to Wace, these men, the duke’s most intimate counsellors, gave him their full backing, but advised calling a second, wider assembly, in order to make his case to the rest of the Norman magnates. Again, although late, this is perfectly credible testimony: several other authors refer more vaguely to William taking consultation. William of Malmesbury, writing in the early twelfth century, says he summoned a council of magnates to the town of Lillebonne, ‘in order to ascertain the view of individuals on the project’. Malmesbury also says that this was done after the duke had received the papal banner, which, if correct, would suggest that this wider council took place in the early spring.

22

Patchy as our sources are, they suggest that at this meeting there was rather less enthusiasm for the projected invasion. ‘Many of the greater men argued speciously that the enterprise was too arduous and far beyond the resources of Normandy’, says William of Poitiers; the doubters pointed out the strength of Harold’s position, observing that ‘both in wealth and numbers of soldiers his kingdom was greatly superior to their own land’. Much of the Normans’ anxiety seems to have hinged on the difficulties of crossing the Channel. ‘Sire, we fear the sea’, they say in Wace’s account, while, according to William of Poitiers, the main concern was English naval superiority: Harold ‘had numerous ships in his fleet, and skilled sailors, hardened in many dangers and sea-battles’.

23

On this matter it is easy to sympathize with the naysayers. Although there is no way of making an accurate comparison between the naval resources of England and Normandy, the impression that

England was the superior power is entirely borne out by the sources. As we’ve seen, the military history of the Confessor’s reign can be told largely in terms of ships. In the 1040s Edward had repeatedly commanded fleets for defence against Viking attack, and instituted a naval blockade of Flanders at the instance of the German emperor. The Godwines had forced their return in 1052 thanks to their ability to recruit a large fleet in exile, and Harold’s victory in Wales in 1063 had been won in part because he was able to draw on naval support. By contrast, the history of Normandy in this period is about war waged across land borders; the only fleets we hear about are the ones raised by Edward and Alfred in the 1030s and, as some Normans might well have pointed out in the spring of 1066, none of these had resulted in success.

24