The Norman Conquest

Read The Norman Conquest Online

Authors: Marc Morris

The

Norman Conquest

THE BATTLE OF HASTINGS AND THE FALL OF ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND

MARC MORRIS

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

To Peter:

my prince

Contents

Acknowledgements

England Map

Normandy Map

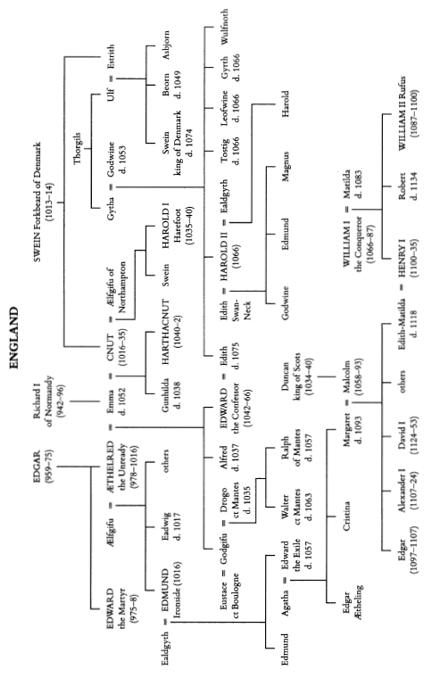

England Family Tree

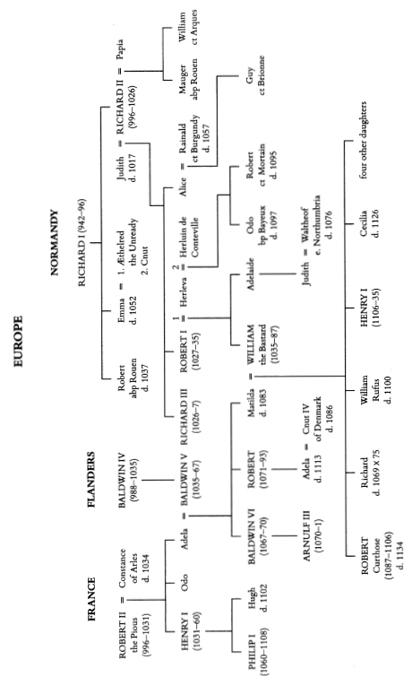

Europe Family Tree

A Note on Names

Illustrations

Introduction

1 The Man Who Would Be King

2 A Wave of Danes

3 The Bastard

4 Best Laid Plans

5 Holy Warriors

6 The Godwinesons

7 Hostages to Fortune

8 Northern Uproar

9 The Gathering Storm

10 The Thunderbolt

11 Invasion

12 The Spoils of Victory

13 Insurrection

14 Aftershocks

15 Aliens and Natives

16 Ravening Wolves

17 The Edges of Empire

18 Domesday

19 Death and Judgement

20 The Green Tree

Abbreviations

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

My thanks to all the academics and experts who patiently responded to emails or otherwise lent advice and support: Martin Allen, Jeremy Ashbee, Laura Ashe, David Bates, John Blair, David Carpenter, David Crouch, Richard Eales, Robin Fleming, Mark Hagger, Richard Huscroft, Charles Insley, Robert Liddiard, John Maddicott, Melanie Marshall, Richard Mortimer, Mark Philpott, Andrew Spencer, Matthew Strickland, Henry Summerson and Elizabeth Tyler. I am especially grateful to Stephen Baxter for taking the time to answer my questions about Domesday, and to John Gillingham, who very kindly read the entire book in draft and saved me from many errors. At Hutchinson, my thanks to Phil Brown, Caroline Gascoigne, Paulette Hearn and Tony Whittome, as well as to Cecilia Mackay for her painstaking picture research, David Milner for his conscientious copy-edit and Lynn Curtis for her careful proof-reading. Thanks as always to Julian Alexander, my agent at LAW, and to friends and family for their support. Most of all, thanks, love and gratitude to Catherine, Peter and William.

A Note on Names

Many of the characters in this book have names that can be spelt in a variety of different ways. Swein Estrithson, for example, appears elsewhere as Svein, Sven, Swegn and Swegen, with his surname spelt Estrithson or Estrithsson. There was, of course, no such thing as standard spelling in the eleventh century, so to some extent the modern historian can pick and choose. I have, however, tried to be consistent in my choices and have not attempted to alter them according to nationality: there seemed little sense in having a Gunhilda in England and a Gunnhildr in Denmark. For this reason, I’ve chosen to refer to the celebrated king of Norway as

Harold

Hardrada rather than the more commonplace Harald, so his first name is the same as that of his English opponent, Harold Godwineson. Contemporaries, after all, considered them to have the same name: the author of the

Life of King Edward

, writing very soon after 1066, calls them ‘namesake kings’.

When it comes to toponymic surnames I have been rather less consistent. Most of the time I have used ‘of’, as in Roger of Montgomery and William of Jumièges, but occasionally I have felt bound by convention to stick with the French ‘de’. Try as I might, I could not happily write about William of Warenne in this book, any more than I could have referred to Simon of Montfort in its predecessor.

Illustrations

PLATES SECTION

Edward the Confessor: detail from the Bayeaux Tapestry

(Musée de

la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

William of Jumièges presents his history to William the Conqueror

(Bibliothèque municipale de Rouen, MSY. 14 (CGM 1174), fol. 116)

. Photo: Thierry Ascencio-Parvy

The tower of All Saint’s Church, Earls Barton, Northamptonshire. Photo: © Laurence Burridge

Arques-la-Bataille. Photo: ©Vincent Tournaire

Jumièges Abbey. Photo: Robert Harding

The Normans cross the Channel: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

(Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library.

Skuldelev 3

(Viking Ship Museum, Roskilde, Denmark)

. Photo: Robert Harding.

Normans burning a house: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry.

(Musée de

la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library.

The White Tower, Tower of London. Photo: Historic Royal Palaces

Colchester Castle. Photo: Shutterstock

Old Sarum. Photo: © English Heritage Photo Library

Durham Cathedral

(Collection du Musée historique de Lausanne)

. Photo: © Claude Huber

TEXT ILLUSTRATIONS

p. 114. Harold swears his oath to William: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

(Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

p. 119. Harold returns to Edward the Confessor: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

(Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

p. 134. Edward on his deathbed: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

(Musée

de la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

p. 139. The coronation of Harold: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

(Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

p. 147. Halley’s Comet: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

(Musée de la

Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

p. 184. The death of Harold: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

(Musée de

la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

p. 185. An unarmed man is decapitated: detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

(Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux)

. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

p. 185. A son of Zedekiah is decapitated

(Los Comentarios al Apocalípsis

de San Juan de Beato de Liébana, fol. 194v, Santa Cruz Library

,

Biblioteca Universitaria, Valladolid, spain)

.

All images of the Bayeux Tapestry are reproduced with special authorisation of the city of Bayeux

.

Introduction

There have been many attempts to tell the story of the Norman Conquest during the past millennium, but none of them as successful as the contemporary version that told it in pictures.

We are talking, of course, about the Bayeux Tapestry, perhaps the most famous and familiar of all medieval sources, at least in England, where we are introduced to it as schoolchildren, and where we encounter it everywhere as adults: in books and on bookmarks, postcards and calendars, cushions and tea towels, key rings, mouse-mats and mugs. It is pastiched in films and on television; it is parodied in newspapers and magazines. No other document in English history enjoys anything like as much commercial exploitation, exposure and affection.

1

The Tapestry is a frieze or cartoon, only fifty centimetres wide but nearly seventy metres long, that depicts the key events leading up to and including the Norman invasion of England in 1066. Properly speaking it is not a tapestry at all, because tapestries are woven; technically it is an embroidery, since its designs are sewn on to its plain linen background. Made very soon after the Conquest, it has been kept since the late fifteenth century (and probably a lot longer) in the Norman city of Bayeux, where it can still be seen today.

And there they are: the Normans! Hurling themselves fearlessly into battle, looting the homes of their enemies, building castles, burning castles, feasting, fighting, arguing, killing and conquering. Clad in mail shirts, carrying kite-shaped shields, they brandish swords, but more often spears, and wear their distinctive pointed helmets with fixed, flat nasals. Everywhere we look we see horses – more than

200 in total – being trotted, galloped and charged. We also see ships (forty-one of them) being built, boarded and sailed across the Channel. There is Duke William of Normandy, later to be known as William the Conqueror, his face clean-shaven and his hair cropped close up the back, after the fashion favoured by his fellow Norman knights. There is his famous half-brother, Odo of Bayeux, riding into the thick of the fray even though he was a bishop.

And there, too, are their opponents, the English. Similarly brave and warlike, they are at the same time visibly different. Sporting longer hair and even longer moustaches, they also ride horses but not into battle, where instead they stand to fight, wielding fearsome, long-handled axes. There is Harold Godwineson, soon to be King Harold, riding with his hawk and hounds, sitting crowned and enthroned, commanding the English army at Hastings and – as everybody remembers – being felled by an arrow that strikes him in the eye.

When you see the Tapestry in all its extensive, multicoloured glory, you can appreciate in an instant why it is so important. This is not only an account of the Norman invasion of 1066; it is a window on to the world of the eleventh century. No other source takes us so immediately and so vividly back to that lost time. The scenes of battle are justly famous, and can tell us much about arms, armour and military tactics. But look elsewhere and you discover a wealth of arresting detail about many other aspects of eleventh-century life: ships and shipbuilding, civilian dress for both men and women, architecture and agriculture. It is thanks to the Tapestry that we have some of the earliest images of Romanesque churches and earth-and-timber castles. Quite incidentally, in one of its border scenes, it includes the first portrayal in European art of a plough being drawn by a horse.

2