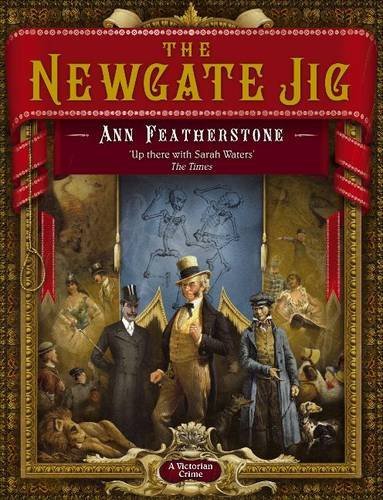

The Newgate Jig

Authors: Ann Featherstone

The Newgate Jig

Ann Featherstone

For

Holly,

the

best of friends

Prologue: Going to See a Man Hanged

There

is nothing more dreadful, surely, than seeing one's own father hung.

All

the horrors of this world, the wars and famines, plagues and pestilences,

cannot compare with the sight of one's father upon the scaffold and the rope

around his neck. It arouses the most extraordinary sensations - of awe, at the

enormity of the event, and despair at one's utter helplessness in the face of

it. One might be forgiven, at the very moment the hangman pulls the bolt, for

going quite mad, tearing at one's hair and crying through the streets. Oh, yes

indeed, quite mad.

Thus

muses aloud, to no one in particular, an elegant gentleman, glass in hand

(though the hour is still early), comfortably established in the upstairs open

window of a tavern. There is much to see, such variety of humanity in the

gathering crowd below: the blind beggar and his attempts to escape the

thieving attentions of a bully, the brightly gowned young woman and her

companion debating whether to purchase a 'Last Confession' from a

street-seller, and a thin, pale-faced boy, perhaps nine or ten years old, whose

clothes were once good ones (a serviceable jacket and trousers, a shirt and

neckerchief), but which are now worn and shabby, in animated

conversation

with an older man. Leaning out of the window, the elegant gentleman can catch

it all if he so desires, for the boy's voice rises and falls like birdsong

above the din.

'You should come away

now, Barney, before it begins. This is no place for you,' the man is saying

with warmth, taking the boy's arm and turning him about. 'Look. That crowd

which is coming and going and looking as though it has daily business in any

shop or counting house, is here for only one reason. That crowd intends to be

amused, and you should not be part of it.'

'I'm not amused,' says

Barney defensively, shaking himself free. '

I've

not come to

laugh.'

'But you'll be standing

cheek and shoulder with those who have,' returns the other, 'with the followers

of the Drop, and those who take pleasure in the misery of their fellows.'

At this, the boy winces

and works his mouth around as if he is about to retaliate, and rubs his red

eyes vigorously with his two fists until the tears, which are threatening to

spring forth in a flood, retreat.

'I

know all about them,' he says, finally, 'and Pa did too.'

'Yes, and that is why

he is here, and why you would do well

not

to be! Your

father was foolish. He should have known better.'

'Someone told lies

about him!' cries Barney. 'Pa said it was all lies.'

'Aye, maybe it was, but

it has still marched him to the gallows!'

Once again, the boy is

moved to reply, and again rubs his eyes until dirt and tears are smeared across

his cheeks.

'Pa has a friend who

will not betray him. A clever fellow.' He swallows hard. 'Pa said he wrote a

letter and gave it to him and he would send it to the Queen and the Lord Mayor

of London.'

Like he is repeating a

prayer so often uttered that the words have become only sounds, his voice

trails away.

'He has it,' says the

other, quietly. 'He has the letter. But go now, while you can.'

Barney shakes his head,

turns about and joins the army of humanity as it tramps on, whilst the older

man debates whether to follow him, watches him out of sight and then, hunching

his shoulders against the cold, posts himself through the next tavern door.

Although the hour is

still early, the crowd is growing by the minute around the platform, which

crouches dark and square and ready against the grey stone of Newgate. All is

grey. Especially the sky which, like a sodden rag, wrings out of itself a dirty

mist, soaking the crowds which flood towards the prison walls. Wrapped tight

against the early morning cold, they are still cheerful, calling to each other

across the foggy streets and pressing into the square. Since before the murky

dawn, the taverns and hotels, butchers' shops and coffee houses have already

had their full quota of paying spectators: every window and doorway that offers

a view of the square is occupied. Now, anxious not to miss a moment's pleasure,

they have climbed trees and posts and walls. A slight young man, with a shock

of orange hair like a human pipe-cleaner, has shinned up a drainpipe onto the

roof of a private house and, despite the best efforts of the owner to get him

down, is perched with his back against the chimney-stack, perished with cold

but determined not to miss a trick.

Barney sees all of this.

And nothing. Allowing himself to be swept along by the crowd, he plunges into

the mass of bodies, determined to get close to the front. Square shoulders rise

up in front of him like a bastion, however, and though he wriggles and squirms

through a forest of legs, and endures hard cuffs and elbows and kicks, he has

eventually to be content with being wedged between a tall man in city-black

(perhaps an undertaker's assistant) and a chimney-sweep, also in dusky attire,

just on his way to work. Thankfully, neither is inclined to conversation and

both are so studiously determined to keep their places that, in so doing, they

allow Barney to keep his. And they are in stark contrast to the wild carnival

crowd pressing around him, hallooing and cheering and so merry that the pie man

and the gingerbread-seller hardly need to call out their 'Here's all 'ot!' or

'Nuts and dolls, my maids!'

But this is no country

fair, and even Toby Rackstraw, up from the country to try the humours of the

city, could not mistake the roars of

this

crowd for

good-natured festivity. No, this is something quite other. Here is a

congregation gathered to worship not some whey-faced saint, but the noose and

the gallows, and as the human tide fills the square and laps the streets

around, there rises from it a murmur of voices like a catechism, telling the

moments as the hour hands of neighbouring church clocks move on.

There is activity

around the scaffold. Policemen push back the crowd and patrol the perimeter,

keeping their eyes peeled for pickpockets and ignoring the taunts of the boys

who, five deep, form the first line of spectators. The rumble of carriages

(for the gates of the prison are close by) signal the arrival of officials, and

the crowd lurches forward to catch a glimpse. A ripple of information - 'It's

the sheriff!' 'It's the judge!' 'Not the clergyman, for he will have been

attending him for the past hour!' - is passed from one to another.

Past

seven o'clock now, the bells ringing out the moments and cheering the spirits

of the crowd which, despite the heavy rain, is still in a holiday mood and

surges to and fro, ripples of laughter rising and falling. The boy is sensible

of the mighty crush behind him and glances anxiously over his shoulder, but his

stalwart companions (who have been silent for almost two hours, the

chimney-sweep chewing slowly upon a piece of bacon fat and only once taking a

long draught from a stone bottle in his bag) stand firm.

At

last, the clock strikes eight, and the boy's unblinking gaze is trained upon the

door.

Such a little door.

When

it opens, such a change comes over the holiday crowd! Jocularity trembles, good

humour shrinks, and there rises an ugly murmur of satisfaction as the platform

fills, until the last, much-anticipated figure appears, when a terrible silence

falls. He is small and slight and, staggering slightly, is supported by one of

his attendants to whom he turns and thanks, only realizing at the last moment

that the gentleman who steadies him so gently, and looks for all the world like

a linen-draper, will shortly assist him into the next world. With a hand under

his elbow, the linen-draper directs him to the great chain dripping black from

the beam and, from that singular position, the loneliest place in all the

world, the man turns to face the crowd. He does not see any single faces, but

his gaze ranges across the expectant mass all turned and fixed upon him. With a

gasp, the boy raises himself up on his toes and sets his face, like a beacon,

towards the figure, as if trying to arrest his look. But the man is stubborn

and will not see him, and the boy mutters something beneath his breath, at

which the undertaker's assistant glances sharply and seems inclined to speak.

'I will serve him out!'

Barney whispers, and then with increasing noise and urgency, as the tears

spring to his eyes, 'I will serve him out! I will serve him out! I will serve

him out!'

The linen-draper is

poised with the hood, the clergyman is done for the day. Even the rain has

stopped. Suddenly the man on the scaffold hears the boy's cry rising above the

humming silence, turns his head madly back and forth, searching the crowd, and

even trying to stumble forward, though the linen-draper prevents him. The boy

continues to call, and the chimney-sweep and the undertaker's assistant, though

a little discomfited, say nothing. But someone must. The congregation is

hungry for the spectacle, and from deep within the throng a voice roars, 'Get

on with it!', and another, 'Murderer!', and finally, 'Stretch his neck!' In an

instant, that general appeal is taken up, whilst on the scaffold the man

unpicks the crowd, frowning in his effort to find one face in ten thousand

until, like a moment of revelation, it is there. The man's ashen face tightens

and the boy, desperate with misery, still cries, 'I will serve him out! I will

serve him out!'

Sturdy leather straps

have been produced, the linen-draper securing the man as quickly as a knot in a

reel of cotton.

The

man struggles.

'No, Barney, no! Let it

be,' he cries, his face broken by grief and fear, and if anyone cared to

listen, they would have heard him cry, 'My son! Barney! My son!'

But this crowd does not

hear. And besides, this crowd needs to have its parties attired in black or white,

needs to be partisan, so that, finding it does not know who, or even what, to

support, it begins instead to bay, at which the linen-draper, with one swift

action, pulls the hood over the man's head and in two steps reaches the post

and draws the bolts. The crowd roars with one voice, but the boy, as if he is

trying to ensure that

his

voice is the last sound the man hears, soars above theirs,

over and over.

'Pa! Pa! Pa!'

Really, it is

remarkable how quickly the streets empty and everything returns to normal

almost immediately the rope ceases twitching. Crowds simply melt away down the

dripping streets. With a clatter of slates, the slight young man releases his

grip upon the chimney pot, slithers down the roof and the drainpipe, winds his

muffler about his neck with all the nonchalance of a circus acrobat, and joins

the departing throng. Now windows are closed, doors fastened against the wicked

weather, and the line of carriages (for the wealthy love nothing better than 'a

good hanging') disappears into the mist, which has dropped again like

transformation scenery. And alone on that stage is the boy. His companions,

having enquired after his well-being (for they are decent enough men and will

tell their wives how they stood next to the boy "oose father was 'ung this

morning' and how he cried out) and pressed a sixpence each into his cold hands,

have gone to their work. He is rooted to the stones, oblivious to the biting

wind which tugs at his short coat and paints his nose and hands the same

scarlet colour as his eyes. His tears have dried into pale veins upon his

cheeks, his lips are dry and chapped. But still he stands.