The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (39 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

A generation before Bagatti, Fr. Clemens Kopp strove mightily to reconcile the many tombs that dot the hillside with scripture. Yet he, too, contrives to locate the village on the slope:

The chain of tombs is an important thread with which to gauge the placement of Jewish Nazareth. According to Jewish law, a tomb had to be at least 50 ells outside the town. Now, the kokhim tombs wind around the spring practically like a wreath. Here, then, must also have been the natural center of the second, the Jewish, Nazareth. The terrain roundabout is fairly flat, and would on this account also initially invite settlement.

[554]

This citation is factually incorrect: the area is not at all flat—the slope at this point rises from 340m to 400m, a steep 15–25% grade.

[555]

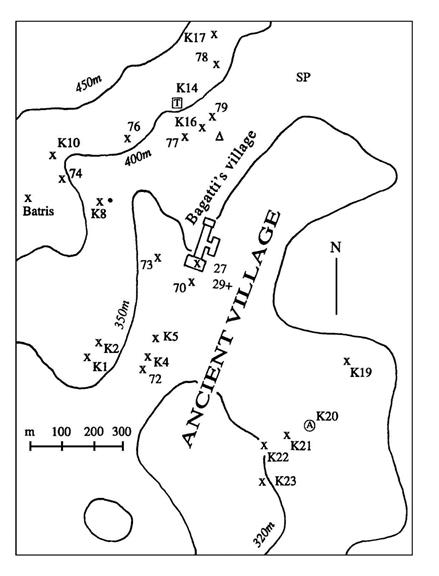

It should be noted that the spring Kopp refers to is not Mary’s Spring at the north end of the basin, but the lesser known ‘Ain ed-Jedide (“New Spring”), a seasonal water source with low volume located near the Mensa Christi church. This spring is marked in

Illus

.

5.2

by a dot near tomb K8. Kopp has relied for his argument on Gustav Dalman, who in 1935 proposed the ‘Ain ed-Jedide site as the central locus of Jesus’ settlement. Dalman admitted that this was “an almost insecure, even unfavourable position.”

[556]

Kopp fully concurs:

Where was the second Nazareth, which was also the town of Christ? It was certainly not built over the first; no pre-Byzantine masonry feature [

Mauerzug

] has thus far been found in the area. Its wealth lay in the natural grottos, easily formed and enlarged artificially out of the soft limestone. Precisely for this reason the place is a poor candidate for house building. In addition, the reaches [

Ausläufer

] of the Nebi Sa‘in—which at a height of 488m form the Nazareth boundary—steeply fall here to the valley floor, which lies at an altitude of 343 m. The attentive observer has always wondered that the town… “sits most uncomfortably on practically a sheer cliff.”

[557]

The attentive observer may wonder at the remarkable obstinacy of the Church as it maintains such an unlikely venue for the town of Nazareth. The tradition would have the Torah-observant Jews of ancient times living among tombs and on a steep slope—while the open valley floor beckons below. In any case,

Illus

.

5.2

shows that tomb K8 fairly ruins the “wreath” of tombs proposed around that spring, lying as it does in the midst of the area both Kopp and Dalman propose for the village.

Yet the scholarly Nazareth literature to this day attempts to squeeze the village of Jesus among the hillside tombs. Thus one dictionary article states:

The location of the tombs of the first century B.C.E. to the first century C.E. disclose that the occupied area extended hardly 300 by 100 meters.

[558]

We shall see, however, that any attempt to locate a settlement on the slope of the Nebi Sa‘in places it not

between

tombs but

among

tombs.

In Kopp’s view Nazareth moved about, while in Bagatti’s view the ancient town existed since the time of Abraham in a narrow space on the hillside. First mapped in the Italian’s 1960 article “Nazareth,”

[559]

this area is contiguous with the venerated area (as demanded by tradition) and is marked “Bagatti’s village” in

Illus

.

5.2

. It places the houses of Mary and Joseph at the southern edge of the village—an interesting proposition, for the venerated area was in fact at the village’s

northern

edge.

Bagatti recognized the necessary boundary set by the tombs further up the hillside, and he accordingly placed the limits of the village at roughly the 360 m contour line. This would still locate habitations on an inhospitable slope. On the positive side, his village situated the inhabitants near Mary’s Spring—no doubt correct.

It is very possible that other (as yet undiscovered and unverified) tombs exist in the sloping areas where Kopp, Bagatti, and others have located the town of Jesus. These areas have not been systematically excavated, for they lie outside Franciscan property. The suspicion of additional tombs is not entirely an argument from silence, as we see from several interesting claims made by Asad Mansur, who authored a whole book on the history of Nazareth in the 1920s.

[560]

Kopp was familiar with Mansur’s work, and writes:

A. Mansur

mentions (

Ta’arich

p. 164) graves “in the form of kokhim” in the hollows under the Greek Bishop’s residence.

[561]

But a structure is not there—the hollows significantly differ in length and breadth from kokhim. He also considers natural protrusions under the Church of St. Joseph

to be kokhim, as well as the bulging extension west from the Grotto of the Annunciation (

ibid

. p. 33). When he therefore also signals graves “in the form of kokhim” [

near a dwelling on the hillside

], caution is required.

[562]

Illustration

5.2

. Middle and Late Roman

tombs of Nazareth.

x kokhim SP Mary’s Spring

A arcosolium • “New Spring” (seasonal)

T trough grave Δ

Greek Bishop’s residence

Despite Kopp’s ardent desires to defend the tradition against the onslaught of science and rationalism, these pages have shown him to be egregiously in error on a number of occasions as regards the Nazareth data.

[563]

One wonders now how much credit to accord his uniform denials of Mansur’s findings. It is possible, of course, that Kopp is right and Mansur wrong regarding every putative tomb claimed by the Arab. On the other hand, it is possible that one or more of these allegations indeed represent Roman tombs situated in the area traditionally claimed for the village. I have deemed it unnecessary to verify every rumor of a tomb on the hillside, simply because the traditional scenario is adequately invalidated by chronology and topography.

It should be mentioned that none of the traditional localizations of the village (by Bagatti, Kopp, or Strange) takes into account the five Roman-era tombs on the eastern side of the basin (K19–K23). Those tombs also signal a village boundary. They show that the settlement was on the valley floor, between the hills (and tombs) to east and west. In postulating a hillside village, the Nazareth literature routinely ignores these more remote tombs—another indication that the tradition proceeds not from evidence, but from convenience.

The size of the village

The Mishna mandates a minimum distance (“50 ells,” or about 25 m) from the nearest habitation, which means that theoretically a ring of tombs could signal the periphery of a village. However, the mishna stipulates neither a maximum distance of habitations from tombs nor a specified distance. Thus, no village periphery is ascertainable merely from the locations of tombs. Those locations can determine only two things: (a) where habitations were

not

(they were not at or near the tombs); and (b) the

general

position of a village. In the case of Nazareth a tomb perimeter (not village perimeter) is obvious, particularly to the east where the five Roman tombs are in an almost straight line. To the west, also, five tombs are in a straight line (including the tombs under the CA). These east-west boundaries tell us not the precise location of the village houses, but the general location of the ancient settlement—on the valley floor. That valley floor, incidentally, has never been excavated.

The tombs nearest to the basin floor are low on the hillside and below the 350 m contour line. This indicates that the Roman village was not on the hillsides. Much less did it creep up them. Evidently, the 500 m between tombs to east and west left plenty of room for the village, so that the ancient Nazarenes at first saw no point in scaling the heights to bury their dead. We can conjecture that the inhabitants hewed tombs gradually farther and farther away as the village grew, and as lower areas on the slopes became used up (not only by tombs, but also by agricultural installations). According to this scenario, the first tombs were those nearer to the valley floor. This is, however, a conjecture.

The valley floor is very spacious, measuring 1.5×0.5 km. All of Jerusalem could fit into that area, and there is no way to gauge how much of that space was empty in antiquity. As alluded to above, from the number and locations of tombs alone we cannot tell how large or small the village was.

It is also hazardous to attempt a population estimate from the number of extant tombs. We recall that the kokhim type of tomb was used for several centuries after its arrival in Galilee. During those centuries the Nazarenes may have constructed new tombs higher up on the Nebi Sa‘in, rather than have reused older tombs closer by. In this case, the village population may have stayed fairly small and constant. On the other hand, if virtually all the tombs represented in

Illus

.

5.2

were in use at the same time (an improbable scenario) then, certainly, the settlement was more than a village, and its inhabitants numbered well into the hundreds.

Regarding the size of the Roman village, we can thus say with a fair degree of confidence only that a substantial settlement existed there during Middle to Late Roman times. This is evident from the great number of kokh tombs in the basin. We can, furthermore, conclude that the settlement was located on the valley floor. Its precise population and dimensions must remain a mystery, barring extensive excavations under modern Nazareth. We cannot say whether the ancient domiciles were scattered about or grouped together, how many there were, nor where on the valley floor they were concentrated. In sum, it is evident that the Nazarenes built tombs on the slopes to the northwest and the southeast, that they numbered perhaps a hundred or more, that they lived on the valley floor, and that they were Jewish. Beyond these few facts we cannot venture.

In light of the preceding discussion, it is interesting that the principal writer on Nazareth in the last several decades, James Strange, has claimed knowledge both of the number of inhabitants and of the square footage of the village at the time of Christ. In a book co-authored with Eric Meyers and published in 1981, he writes:

Judging from the extent of its ancient tombs, Nazareth must have been about 40,000 square meters in extent, which corresponds to a population

of roughly 1,600 to 2,000 people, or a small village.

[564]

This curious passage poses a number of problems. First of all, it is obvious that Strange and Meyers are not considering the valley floor in their calculation, but suppose that some other plot of land was the locus for the village. This is clear because the relatively flat, habitable area of the valley floor (roughly below the 340 m contour line and between tombs to east and west) encompasses a much larger area than calculated in the above citation—approximately 36 hectares (360,000 square meters or 89 acres), which is the aggregate equivalent of a square with sides extending well over half a kilometer. In comparison, Strange’s figure of 40,000 square meters corresponds to a modest plot of land 200 m square. Not coincidentally, perhaps, this corresponds to the area of Bagatti’s village between the venerated area and tombs 77, K16, and 79 (

Illus

.

5.2

), while allowing a buffer (“50 ells”) between habitations and tombs.