The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (38 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

The preceding discussion alerts us to the fact that the greatest interest over the centuries has focused on two sites that are in fact peripheral to the actual Jewish settlement. The Franciscan venerated area is located in a cemetery, which was

ipso facto

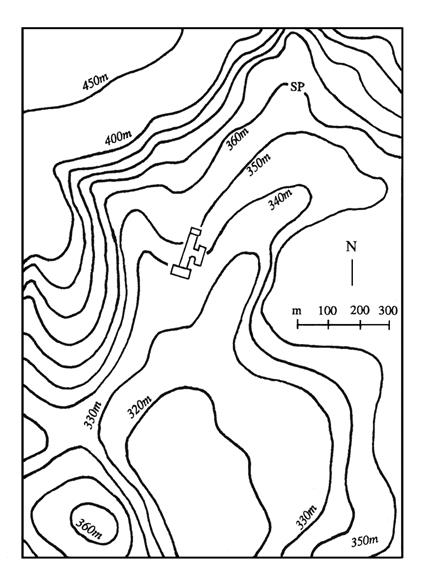

outside the inhabited part of the village. The Greek Church of the Annunciation is located at the 360m elevation halfway up the northern slope. Topography indicates that it was also outside the settlement.

Though Nazareth did not yet exist at the turn of the era, we have not addressed where precisely in the basin the Jews of later Roman times built their habitations. In itself the question is scarcely important, and the answer, in any case, seems obvious—topography indicates that the people lived on the valley floor. The question bears closer investigation, however, simply because the tradition has made such persistent, contrary, and extravagant claims regarding the venerated area and the steep hillside of the Nebi Sa‘in. There are three basic reasons why those claims are false, that is, why the hillside could not have been inhabited at the time of Jesus. They can be summarized in three words: chronology, topography, and tombs.

We have already considered the chronology

in extenso

. The material evidence shows that Nazareth came into existence after the First Jewish Revolt (Chapter Four).

As regards topography, it is remarkable that the tradition locates the entire Roman settlement on the slope of the Nebi Sa‘in and above the 350 m contour line.

[542]

The area could hardly be less conducive to ancient dwellings. Bagatti labels the traditional location on a map accompanying his 1960 article, “Nazareth” (marked in

Illus

.

5.2

with the words “Bagatti’s village”).

[543]

The rocky, steep, and cavernous nature of the limestone hillside is self-evident and, besides, the archaeologist was quite aware that a number of tombs dotted the hillside.

[544]

In the face of all these negative elements, there must have been some overriding reason that demanded a hillside location. Why, indeed, has the Church since IV CE insisted upon a hillside location for Nazareth?

As with so much in the tradition, the answer ultimately lies in scripture. We recall the Lukan passage where Jesus shocks his neighbors—indeed, insults them—by insinuating that the Nazarenes rank below foreigners in the eyes of God:

When they heard this, all in the synagogue

were filled with wrath. And they rose up and put him out of the city, and led

him to the brow of the hill on which their city was built

, that they might throw him down headlong. But passing through the midst of them he went away. (Lk 4:28–30)

[545]

[Emphasis added.]

Illus

.

5.1

. The

topography

of the

Nazareth basin.

Accordingly, from the time Christian pilgrims first came to Nazareth until the present day, they have expected (even insisted) that the settlement be on a hill. Through the centuries, the Church has accommodated this expectation and faithfully located the domiciles of Joseph and Mary on the hillside. Already in IV CE the first ecclesiastical structure was built in the venerated area. Until relatively modern times the uneven, sloping terrain, and the cavernous nature of the ground have conspired to prevent the construction of private dwellings on the mountainside. But the unfavorable characteristics of the area did not prevent the construction of ecclesiastical structures, a fact which attests to the power of tradition to overcome almost all obstacles.

The Franciscan Church of the Annunciation (and its predecessors) memorializes an habitation that was never there. It is not a monument to any humble dwelling, but a monument to a cherished

idea

embodied in scripture. That idea is grand, and the church standing there today is fittingly massive, imposing, and grand. It has nothing to do with the Jewish village of later Roman times. It has everything to do with ideas, ideas enshrined in the New Testament scriptures. In turn, the

expectations

of pilgrims have been fully met: there is a town on the hillside, as Luke wrote. There is a cave associated with the Holy Family, as pious tradition imagined. There is even the humble “workshop of St. Joseph” (the CJ) nearby, where he plied his trade as a carpenter (Mt 13:55). Thus, the venerated structures reflect scriptural requirements quite to the exclusion of evidentiary or historical considerations.

The tombs of the Roman era

The third basic reason, mentioned above, why the hillside could not have been inhabited at the time of Jesus is the presence of tombs. In Judaism, man was created in the image of the divine (Gen 1:26). God breathed the spirit (

ruach

) into Adam, making him a living being (Gen. 2:7). That spirit is a gift and returns to the Lord at death (Eccl. 12:7). Thus, the dead person is ritually impure, and contact with a corpse must be avoided.

[546]

Uncleanness was infectious, so that a person could become unclean through contact (Lev. 5:3). According to Torah, three forms of uncleanness were serious enough to exclude the infected person from society: leprosy, bodily discharges, and impurity resulting from contact with the dead:

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Command the Israelites to put out of the camp everyone who is leprous, or has a discharge, and everyone who is unclean through contact with a corpse; you shall put out both male and female, putting them outside the camp; they must not defile their camp, where I dwell among them. (Num 5:1–3).

Impurity from contact with a corpse lasts seven days (Num 19:11). Elaborate rituals are necessary to remove the impurity. Thus, the Talmud mandates that habitations be a minimum distance (“fifty ells,” or about seventy-five feet) from the nearest tomb.

[547]

The ell (Heb.

ammah

) is a unit of length derived from the human body, typically measuring six handbreadths.

[548]

Calibrating 3 inches for each handbreadth (“the width of four fingers”), then 50 ells = 300 handbreadths = 900 in = 75 ft = 25 yds = 23 m. Thus, tombs had to be outside the town, and at least this distance from the nearest habitation.

Hence, the presence of tombs automatically disqualifies the existence of ancient habitations at the same sites, at least as regards Jewish settlements. And we know that ancient Nazareth was indeed Jewish. This can be inferred from the following facts: (a) the arrival of the priestly family of Hapizzez in II CE; (b) the recorded Jewishness of the village in accounts of the Church Fathers and others;

[549]

(c) the presence of stone vessels among the earliest evidence; and (d) the consistent lack of pagan symbolism on the pottery finds.

No less than twenty-five later Roman tombs have been excavated in the Nazareth basin. Most are of the kokhim type. More tombs doubtless exist, for only a small part of the basin has been excavated. Not infrequently a tomb is discovered during the construction of a house, and rumors are common regarding the existence of ancient tombs here and there in the basin. In addition, we shall soon consider a number of tombs that have been documented in one form or another but whose existence is contested by the tradition. In any case, the score or more kokh tombs must postdate 50 CE, as we have seen.

[550]

Given the Jewish prohibition against habitation in the vicinity of the dead, the emplacement of these Roman tombs furnishes a clue as to the location of the ancient settlement. A glance at

Illus

.

5.2

shows that they exist on both the western and the eastern slopes of the basin. From this it is quite clear that the ancient settlement was between the two slopes and on the floor of the basin. Topography confirms this. In contrast to the hillsides, the valley floor offers several advantages for the construction of dwellings: it is relatively flat, it is less rocky and has greater depth of soil, and it is not encumbered with caves, hollows, and pits.

Yet Bagatti and the tradition do not view the topography of the basin in this way. Indeed, they ignore the tombs to the east and claim to see a ring of tombs on the hillside itself. The tradition, of course, has been concerned with demonstrating that the residential portion of the settlement included the area of the venerated sites. This is the subject of the first major section of Bagatti’s 1960 article “Nazareth,” in the

Dictionnaire de la Bible.

The article was written towards the midpoint of the archaeologist’s decade-long excavations. In French, it takes up no less than twelve columns of text and includes a full-page topological map of the Nazareth basin. Like the author’s 1955 writing, the article is provisional and makes no pretense towards completeness. (For example, the Bronze Age is nowhere mentioned.) It is divided into three parts. The first, entitled “The Ancient Village,” begins as follows:

THE ANCIENT VILLAGE. On the slope of the hill, between the Church of St. Joseph

and that of the Annunciation, we have discovered abundant and characteristic finds which permit the localization of the ancient village,

already existing in Iron II

. This is all the more important in that occasional excavations carried out in the environs and recently well-studied have made us aware that

similar finds do not exist elsewhere, thus excluding some other localization

[

of the settlement

]. We were able to identify silos

serving to warehouse stores, cisterns

for water or wine, presses

for grape and olive, millstones, grottos, and masonry debris.

[551]

(Emphasis added.)

In Chapter One we verified that the settlement (probably Japhia) existed in Iron II but did not continue after that period. As for the claim that “similar finds do not exist elsewhere” in the basin (that is, outside the putative hillside area marked for settlement by the tradition), in his 1960 article Bagatti attempts to substantiate this by reporting on four digs made during construction activities in various parts of the basin.

[552]

The problem is that all four of those excavations were conducted above the 350 m contour line, thus ignoring the most obvious localization of settlement—the valley floor. After all, no one should expect to find ancient habitations on the hillsides, nor is it surprising that Bagatti did not find any there. He is eerily silent about the valley floor. In other words, the archaeologist looked where he needn’t, and where he should have looked—he didn’t.

Elsewhere in the same article Bagatti writes:

The

necropolis. – The map given [

in

] fig. 599 locates the ancient remains of Nazareth: one notes there the ensemble of the Annunciation, at the center, and in the environs, marked in black, a series of tombs to the north, to the west and also some to the south. These are the remains actually known of the ancient necropolis…

[553]

In contrast, a glance at

Illus

.

5.2

shows that the tombs to both east and west of the valley floor form a larger “ring” that is eminently more probable than the one perceived by Kopp and Bagatti. Those tombs localize the settlement on the valley floor, not on the hillside, and not in the venerated area (which itself contains tombs).

Very little of the Nazareth basin has ever come under the archaeologist’s spade, and most of the area is now thoroughly urban and built over. It is not impossible that other, undiscovered, tombs of the Later Roman period exist in the very hillside area that Bagatti signals as the

ville antique

.