The Men Who War the Star: The Story of the Texas Rangers (5 page)

Read The Men Who War the Star: The Story of the Texas Rangers Online

Authors: Charles M. Robinson III

Tags: #Fiction

Judge Roy Bean (

center, with

white beard

) stands with friends in front of the Jersey Lilly Saloon, which served as his courthouse. If there was a way to get around the law and hold the fight, the shifty old judge would find it.

REVOLUTION ON THE RIO GRANDE

Capt. Monroe Fox and two Rangers drag the bodies of radical leader Luis de la Rosa’s men, who had been killed in a fight at Norias during the border disturbances that accompanied the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1917. Fox desecrated corpses as a terror tactic against bandits and revolutionaries but succeeded only in alienating much of the staunchly Catholic

tejano

community.

The destruction of a train by radicals at Olmito resulted in the Rangers killing innocent people.

HOLLYWOOD AND THE RANGERS

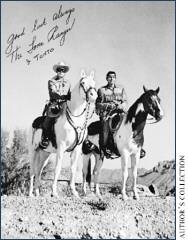

The entertainment world’s most durable Ranger is the Lone Ranger (

left

), portrayed by Clayton Moore in this giveaway premium photograph from the 1950s. According to the storyline, he was the sole survivor of a company of Texas Rangers ambushed and massacred by badmen.

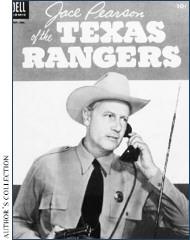

Actor Joel McCrea portrays Ranger Jace Pearson on the cover of a Dell comic book based on the radio and television series

Tales of

the Texas Rangers

. Although the programs were based on actual cases, the comic-book plots were imaginary.

PART 1

THE FIRST RANGERS

Chapter 1

Life and Death in a Harsh Land

“Texas Ranger” is a blanket term that has meant different things

at different times. Since 1874, it generally has described a full-time, professional state peace officer, originally charged with protecting the citizens from Indians and desperadoes, and later with investigating crime in the modern sense. Prior to 1874, however, the term was, in the words of one nineteenth-century writer, “somewhat vague when sought to be historically applied to the various volunteer and irregular organizations that have figured in the frontier service of Texas.”¹

The earliest ranger-style forces in Texas often were minutemen—much like those of colonial America—who agreed to hold themselves ready and come together under the authority of the Texas government when necessary, after which they would return home and resume their normal lives until needed again. Other times they might be volunteers who served for a specific length of time, electing their own officers, much the same as the ninety-day volunteers of the Union Army. Occasionally, they were ad hoc companies formed with the sanction of the local community to handle a specific emergency—and on the frontier at that time, the sanction of the local community was all the authority they needed.

During the period of the Republic through the Civil War, which is to say from 1836 to 1865, Rangers often served as auxiliaries for the military, and sometimes they were even incorporated into the army—at least theoretically. Yet the Texas Ranger always retained his separate identity and was never a soldier in the classic sense. He belonged to a unique group of men—neither military nor civil—banded together in an official or semiofficial capacity to defend the frontier. As Sgt. James B. Gillett, one of the outstanding Rangers of the nineteenth century, explained:

Scant attention is paid to military law and precedent. The state furnishes food for the men, forage for their horses, ammunition, and medical attendance. The ranger himself must furnish his horse, his accoutrements, and his arms. There is, then, no uniformity in the matter of dress, for each ranger is free to dress as he pleases and in the garb experience has taught him most convenient for utility and comfort. A ranger, as any other frontiersman or cowboy, usually wears heavy woolen clothes of any color that strikes his fancy. . . . A felt hat of any make and color completes his outfit. While riding, a ranger always wears spurs and very high-heeled boots to prevent his foot from slipping through the stirrup, for both the ranger and the cowboy ride with the stirrup in the middle of the foot.²

The Ranger was a unique frontiersman on a unique frontier, for in all the annals of the American West there was nothing quite like Texas. One single state held every hope and hardship that pioneers faced in the nation’s westward expansion. Texas’s natural barriers included rivers, mountains, deserts, and extremes of weather. Some of the most tenacious Indians on the North American continent contested white pretensions of ownership. Nevertheless, the Texans settled their vast frontier within a single lifetime. Beginning as outsiders in a neglected province of Mexico, they turned that province into a sovereign republic, and made the republic into a prosperous state.

In building Texas, people on the frontier depended on the citizen-ranger far more than on any soldier or sheriff, because he was one of them and he knew the dangers they faced. He also understood the people he had to fight and adjusted his thinking accordingly. He risked his life because he had family and friends to protect, and sometimes he lost his life. For death was a constant companion to the Rangers during the first hundred years of their existence in a state that assumed more or less its present boundaries in 1850.

At 268,601 square miles, twentieth-century Texas is almost 56,000 square miles larger than France. The original area was even greater, but as part of the Compromise of 1850, the northwestern portion of the state was ceded to the United States and partitioned, eventually to become sections of New Mexico, Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. Despite its size, its 1992 population was estimated at only 17,655,650, which is roughly as many people as Texas can conveniently support.³ Like everything else about the state, this small population in relation to its immensity is dictated by two great immutable facts—climate and geography. The eastern half of the state is arable, has a reasonably secure water supply, and can support moderate development; the area to the west is arid and cannot. Most population centers are in east and central Texas; as one proceeds westward, cities become smaller and more isolated.

Most of the state is a plain shelving into three distinct tiers rising one above the other almost like stairs. The lowest is a relatively fertile coastal prairie anywhere from fifty to two hundred miles wide, where American settlement began and where the Texas Rangers were created. The coastal region ends at an escarpment of rugged hills that lead up to a second tier consisting of rolling plains that gradually slope to the northwest. These plains abruptly halt at the caprock, a line of sheer cliffs hundreds of miles long and seamed with deep, rugged canyons. Above these cliffs is the final tier, the Staked Plains, or

Llano Estacado,

to use their local names—flat and featureless tableland that reaches beyond the horizon to Canada, and gives credence to a local saying that there is nothing between Amarillo, Texas, and the North Pole but barbed wire. In the far western part of Texas, beyond the Pecos River, the terrain assumes yet another character totally different from the other three. Here one struggles among the highest mountains in the state, descending from the passes onto the flat, dry, sand-swept floor of true desert.

Even within one particular type of terrain, no two areas have the same environment. In the southernmost tip of Texas, the Rio Grande marks the transition from tropical jungle to temperate forest. Here the whitetail deer and bobcat of the north coexist with the coatimundi and ocelot of the south, and until it was hunted out midway through the twentieth century, the jaguar was considered a native.

The temperate forest hugs the river. A few miles above the mouth of the Rio Grande, the beaches of the coast give way to a region that is less a prairie than a desert. In modern times it is kept green and lush by irrigation from the Rio Grande and underground aquifers, but left to itself it soon would revert back to dust, scrub grass, and cactus. In the immediate coastal area, the easterly breezes from the Gulf of Mexico meet the southwest wind from the Chihuahuan desert, forming a pocket of hot, damp air and making the area around Brownsville a Turkish bath in summer. Farther north, the coast blends into true prairie with tall grass and groves of live oak until, in east Texas, one reaches the vast pine forests of the American South.

Along the escarpment, in the Hill Country, and beyond, spring rains carpet the land with wildflowers—blue, yellow, red, and white—wrapping around hills and buttes and extending as far as the eye can see. But with summer the flowers wither, the color fades to a dull beige, and dust coats everything.

ONLY SINCE THE

1950s, with construction of superhighways and expansion of commercial aviation, has travel been convenient in Texas. The Rangers gained their fame before the age of the automobile and airplane, traversing the country by horseback. In those days, the six-hundred-mile trip from San Antonio to El Paso took weeks through broken mountains and across searing desert. Here, Texans say, every form of plant or animal life bites, slashes, stabs, or stings. One shakes one’s blanket for rattlesnakes and checks boots for scorpions and venomous spiders. The native cacti include a low-growing species that botanists know as

Echinocactus texensis,

but that locals call “horse crippler,” with good reason.