The Men Who War the Star: The Story of the Texas Rangers (2 page)

Read The Men Who War the Star: The Story of the Texas Rangers Online

Authors: Charles M. Robinson III

Tags: #Fiction

Seventy years later, it still holds true.

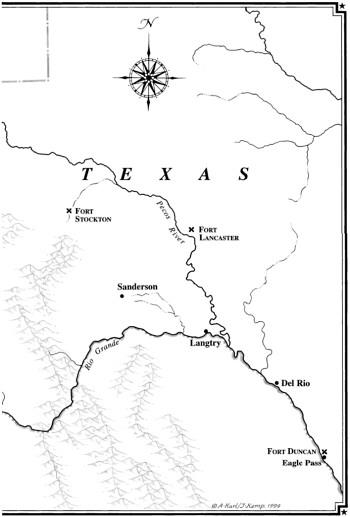

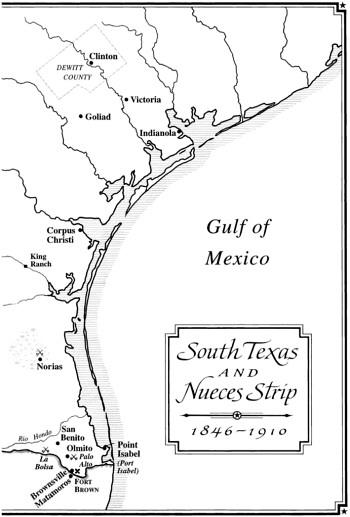

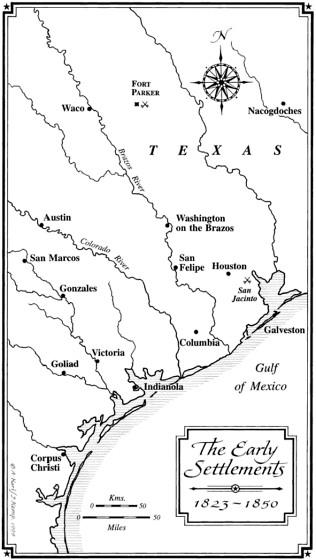

Texas historian Harold Weiss, Jr., recently divided Ranger history into three distinct periods: 1823–74, the era of the citizen-ranger who defended the frontier; 1874–1935, the era of the professional Western law-man who ultimately developed into a career peace officer; and 1935 onward, when the Rangers became a modern police force.³ Today’s Rangers assist local law enforcement agencies in criminal investigations, investigate public corruption, provide security for the governor when he or she travels in the state, and oversee elections when the potential for fraud exists. As such, the modern Texas Rangers are beyond the scope of this book. This is the story of the “classic” Rangers from the formation of the first frontier defense company in 1823 through the era of Mexican rule and the Republic of Texas, the Mexican War and Civil War, Indian fights, hunts for outlaws, and suppressions of blood feuds. The story of these classic Rangers ends with the overhaul of the service in the mid-1930s, after which the service entered the world of modern criminology.

Ranger history often is controversial. Part of this is because much of the material comes from sources in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the lines between good and evil were much more clearly and arbitrarily established than they are today. Good was white. Evil was black. The possibility that there might be large areas of gray was not considered. Evil itself being foul, any means to combat it—fair or foul—were justified. This often colored the actions of the Rangers, as well as their recollections of events.

Aside from the difficulty in obtaining a balanced and complete picture of the Ranger character, there is also a paucity of accurate information on their performance, a situation encountered more than eighty years ago by pioneer historians Andrew J. Sowell (himself a former Ranger) and James T. DeShields. DeShields described the problem in 1910, as he and Sowell tried to sift through the many fights of Capt. Jack Hays’s Rangers some sixty years earlier.

One of the difficulties encountered . . . has been in securing reliable material—sifting the facts from the fiction; and in fixing exact dates and even locations to the incidents known to have transpired, and in the manner presented. This arises from the fact that most of the reports of engagements and records of the Adjutant[’]s office of the Republic were lost when the Capitol burned in 1881. The narratives of fights as supplied by survivors of that time, and even participants, while they bear the stamp of truth and in the main are no doubt reliable and sufficiently full are often lacking of dates and bearings.

4

Hays’s Rangers are a good example of the blurred line between myth and reality. By his twenty-fifth birthday, Hays was already a legend in Texas, and he later became prominent in California as a businessman and public official and one of the founders of Oakland. During his ranging days, his men were in the field almost continuously, and the tales of their many fights are often confused. Many times there is only an oral account transcribed many years after the events purportedly occurred. Some stories have been disputed because the names of the witnesses do not appear on muster rolls for the unit in question at that particular time. But the muster rolls contain large gaps, and the fact that a person’s name is missing from the list doesn’t necessarily mean he was not part of the unit at the time.

The Capitol fire cited by DeShields was the second destruction of Ranger records; the Adjutant General’s Office previously burned in 1855. Fires, deterioration, thoughtless disposal, and ordinary theft have taken their toll. Files that were known to exist sixty years ago can no longer be found. Ledger books refer to letters and reports that have long since disappeared. Others exist only as transcript copies in the University of Texas’s Center for American History. As Donaly E. Brice, reference specialist at the State Library and Archive in Austin, observed in 1996, “After 150 years, it’s a miracle we have anything.”

5

Yet much does remain, and a fairly comprehensive history can be assembled—at least from the Ranger point of view.

Like any organization closing out its second century, the Rangers have skeletons in their closets. Ranger officers were not always careful about the men they enlisted, and some were troublemakers or worse. During the border disturbances of the early 1900s, some Ranger units were little more than officially sanctioned lynch mobs, earning contempt even from other Rangers. In the Starr County farm labor disturbances in the late 1960s, the Rangers were justly accused of being strikebreakers, and their methods ultimately were condemned by the United States Supreme Court. In the early 1970s, there were even calls in Texas for their abolition. More recently, they have been involved in controversy over female and minority members, in part because they rushed too quickly into female and minority hiring, sometimes enlisting by quota or political pressure rather than talent. Until the McLaren standoff, many believed the Rangers were an anachronism, and there was widespread feeling that they needed to reexamine their mission as they approached the twenty-first century.

Yet the McLaren incident confirmed the belief of most Texans that the Rangers should continue as the senior state law enforcement agency. More than other peace officers, the Ranger continues the frontier tradition of a self-reliant person, capable of making decisions on his own, without consulting some centralized authority. And as Capt. Barry Caver demonstrated with McLaren, a modern Ranger acting on his own can handle a situation responsibly and with dignity for himself and the state.

In telling the story of the Texas Rangers, I have concentrated on the “forgotten” Rangers—the citizen-militiamen who answered the call to defend their homes during the period of Mexican rule, those who served honestly and ably during the Civil War and Reconstruction, and those who served less nobly during the border disturbances from about 1915 to 1918. Despite the hatred and prejudices of the past, and the occasional rogue Ranger, each Ranger performed his duty as he saw it. Each was molded by the time and place in which he lived.

EARLY DEFENDERS OF A RUGGED LAND

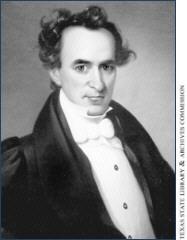

Stephen S. Austin was the father of American colonization in Texas. By combining the minuteman ranger concept of the southeastern United States with the existing Spanish-Mexican frontier militia system, he helped create a uniquely Texan institution.

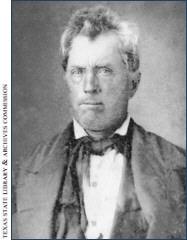

Edward Burleson was a competent commander of the early volunteer Rangers, but his shoot-first-ask-questions-later attitude toward Indians helped spark a general uprising in 1836.