The Mapmaker's Wife (36 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

Isabel realized her mistake at once. She had paid the Canelos Indians in full ahead of time. That was the custom, and they had demanded the advance pay, but the arrangement had removed any incentive for them to remain until they reached Andoas. Doing so would simply have led to a more arduous return journey to Canelos. She and the others were now alone on a river they knew nothing about. Their only salvation was that the Indians had left them the canoe, apparently choosing to make their way back to Canelos on foot.

There was little possibility that they might do the same.

“We didn’t know the path through the woods [to Canelos],” the French doctor Jean Rocha later told the priest at Andoas, “and it was even less possible to return by the river, since it was flowing very fast, filled with rocks and sticks. Even the Indians who were experienced in navigating the river found it terrible, and so we determined to lower ourselves on the river under the guidance of God, assigning to everyone a job.”

Rocha took the place of the navigator up front. Joaquín, Isabel’s slave, assumed the role of steersman in the rear, while Isabel’s two brothers, Juan and Antonio, took paddles in hand and, seated in the middle, “rowed,” hoping to propel them faster through the slower sections of the river. Isabel and the others—her nephew Martín, her two maids Tomasa and Juanita, the Frenchman’s companion Phelipe Bogé, and Rocha’s slave Antonio—sat scattered about the boat.

That day the river rose, and they could see it was raining in the mountains. A large tributary, the Sarayacu, flowed into the Bobonaza, adding to their sense that the river was growing exponentially in power and force. As Rocha was to tell the priest in Andoas, “None of us had any skills, which put the canoe at every instant in a million dangers, now against a stick, then against a rock, with the canoe filling with water often in the rough spots, with evident risk of going under.” At such moments, Isabel clutched the two gold chains around her neck and silently asked that the “Virgin hear their prayers.” It seemed that they would not survive the day. But they did, and at noon on the following one, they came upon a most welcome sight:

“We saw a canoe,” Rocha related,

and next to it footsteps, and following the path to a hut, we found an Indian convalescing from the smallpox. He appeared like death, but this man was alive, and we were overjoyed at seeing him. He was in a state of total abandonment, as all his family had been killed by the smallpox. He was content to get on board and take over management of the canoe. Although he was weakened by his illness, he was animated by his skill.

The rest of that day and the next two—October 29 and 30—passed without incident. The Bobonaza continued to widen after yet another large tributary, the Rutunoyacu, flowed into it from the north. The landscape changed here as well. They were now more than 100 miles below Canelos, and the river had spilled out into a

floodplain, snaking back and forth across the flat land, creating a swampy landscape of oxbows and lagoons. They were not moving at any great speed—indeed, at times it seemed they were just drifting along at a leisurely pace—and yet they could see the river pushing along huge logs and branches, a great force that kept them on edge. No one said much; they were all alone in their thoughts. Then, late on October 31, a gust of wind blew Rocha’s hat into the water, and their pilot,

“stooping to recover it,” as Jean later wrote, “fell overboard, and not having sufficient strength to reach the shore, was drowned.”

Everyone was too stunned to move. One moment the Indian was there, behind them, safely steering the canoe, and the next he was slipping beneath the water, his arms flailing as the current carried him off. And now the canoe was “again without a steersman, abandoned to individuals perfectly ignorant of managing it.” They were adrift in the current, Joaquín trying to scramble past Isabel to the rear without upsetting the boat. In very short order, the canoe was turned sideways by the current, and, striking a log, was “overset.”

They spilled into the river, and so too did the woven baskets with all of their goods. Isabel, pulled under by the weight of her heavy silk garments, came up gasping for air and grabbing for the overturned canoe, as did everyone else. They were not far from the river’s edge, and by clinging to the upside-down boat, they were able,

“with great work, to arrive at a beach.”

They were now in a dire predicament. Although they were able to retrieve most of their supplies, Isabel and her two brothers were so spooked by the Indian’s drowning and their own near escape that they resisted getting back into the canoe. They built a hut that night as far up on the beach as possible, planning to wait there for a day or two, to see whether the river would drop. But it did not. “Each day,” Rocha said, brought “greater dangers.” At last—on their third day on the beach—Rocha “proposed to repair to Andoas” and seek help. By everyone’s reckoning, they were “five or six days journey from Andoas,” and Isabel and her two brothers, with the river at such a height, were still not willing “to trust themselves

on the water without a proper pilot.” Rocha laid out his rescue plan: He, Bogé, and Joaquín would take the canoe, and since it would no longer be so loaded down, they should be able to steer it fairly easily. They would hurry to Andoas, where they would gather “a proper complement of natives” to come back upriver and rescue those left behind. Isabel and the others could expect to see a well-supplied canoe return within two weeks, three at most.

At ten o’clock the next morning—the date was November 3—Rocha and the others left. Those remaining on the sandbar stood together as they paddled off, the canoe passing around a bend and slipping from their sight. Only then did they realize what they had done. They were now marooned on this spit of sand. They were miles from the nearest speck of civilization, alone in a fearsome wilderness, and they had to rely on the others to return. As they looked around the sand and took a quick inventory of their supplies, their panic rose. Although they had a fair amount of food left, enough for three weeks if rationed, they could see what was missing: Rocha, while packing up, had taken

“especial care to carry his effects with him.” He had left none of his belongings behind.

*

As a result of road construction, the river below Baños no longer passes through a channel this narrow.

*

In South America, reptiles in the

Alligatoridae

family are more properly known as caimans. The caiman has a more heavily armored belly than the North American alligator.

T

HE SANDBAR THAT

I

SABEL

’

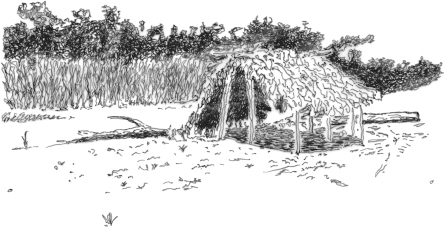

S PARTY

was stranded on was perhaps 200 feet wide and several hundred yards long. They had built their hut, as Rocha later told the priest at Andoas,

“at the top of the beach, located in a way that it could not have been more insulated from the growing river.” They had also woven palm fronds together into beds, which made their rancho, as such beach shelters were called, at least somewhat comfortable. They were, however, surrounded by a wilderness that they did not dare enter. They were now in the very part of the Amazon basin that is most inhospitable to humans.

Much of the Amazon rain forest is relatively benign and not overly difficult to walk through, as long as one is equipped with a compass or is on a path. The dense canopy blocks out so much sun-light that there is only a sparse amount of vegetation on the forest floor. Leaves and other plant debris that fall to the ground are quickly chewed up by hordes of ants and beetles, and while there are poisonous snakes and other dangers in a rain forest of this type, they are not so overwhelming as to chase all humans away. Even

the mosquitoes and bugs are not too nettlesome in a mature rain forest. But the forests along the lower Bobonaza, where Isabel and her party were stranded, are a different case. At this point, the river’s descent from the Andes is over, and as it spills into the huge lowland that is the Amazon basin, it turns the landscape into a marshy swampland.

The jacumama that Ulloa and Juan wrote about, cautioning that this “man-eating serpent delights in lakes and marshy places,” is known today as the great anaconda. Growing to as much as thirty feet long and weighing as much as 500 pounds, it lies in wait along the river’s edge and in lagoons, feeding—in the eighteenth century—on a bountiful supply of capybaras, large birds, peccaries (a piglike animal), 400-pound tapirs (a hoofed mammal), and young caimans. The constrictor kills by coiling itself around its prey and strangling it.

The poisonous snakes that haunt the banks of the lower Bobonaza are of two kinds: coral snakes and pit vipers. The corals are recognizable by their red and yellow bands warning predators to stay away. Their powerful venom can cause heart and respiratory failure. The poison from the fangs of pit vipers, which have distinctive triangular heads and catlike eyes, kills by rapidly destroying blood cells and vessels. Most pit vipers, such as the fer-de-lance, hide coiled beneath forest-floor debris. However, the palm pit viper likes to hang from a branch, looking for all the world like a dangling vine, remaining perfectly still until striking out at any passing bird or warm-blooded animal that mistakenly brushes up against it. During October and November, snakes on the lower Bobonaza also tend to be on the move, for this is the season in which they shed their skins and travel to new holes.

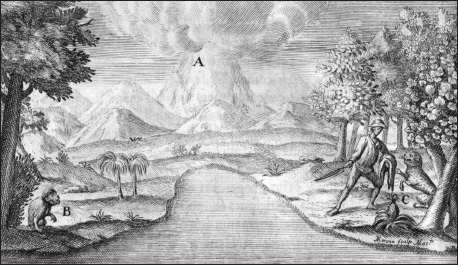

Jaguars still roam this region as well, although not in the numbers they did in the eighteenth century, when they were called “tigers” by the Spaniards. They prowl the rivers and marshes, hunting monkeys, tapirs, peccaries, capybaras, and juvenile caimans. Their prints are often found on sandbars. At times, in the early morning hours, a jaguar still full from a night of successful

hunting will stretch out on a log floating down a river, catching some sun.

An explorer fights a “tiger” in the jungle.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749)

.

Even the river harbors a host of threatening creatures. In the lower Bobonaza, there are electric eels that can deliver a 650-volt jolt, blood-sucking leeches, stingrays with venom-laced tails, and a bizarre catfish called the candiru. Thin as a catheter, the candiru has the nasty habit of swimming up body orifices—the human urethral, vaginal, or anal opening—where it fixes itself by opening an array of sharp fin spines, triggering almost unendurable pain.

Isabel and the others, having been warned about all these dangers, clung to the sandbar. They were prisoners of their little spit of beach, near a spot on the Bobonaza known today as Laguna Ishpingococha. Their days quickly settled into a routine. They would awaken at the first break of light, often to the sound of monkeys chattering in the nearby trees. This was the best hour of their day. The light was soft and the air relatively cool, the temperature having dropped to seventy-five degrees Fahrenheit or so during the

night. Herons, swallows, and other river birds swooped about, and across the way, there was a beautiful ceiba tree in flower. All of the leaves had dropped from its majestic crown, and its seeds would drift across the water, held aloft by silky, cottonlike fibers. Isabel and the others would eat upon rising, taking from their supplies a serving of dried potatoes or corn or a small piece of jerky.