The Mapmaker's Wife (29 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

A much different scene unfolded once La Condamine and Maldonado entered Portuguese territory. Below the Napo, the

banks of the Amazon were silent, even empty. They traveled for several days and nights

“without coming across any signs of life.” This was a stretch of river where Acuña, a century earlier, had come upon one village after another, the natives farming and raising turtles in pens. That world was gone. There were five lonely Carmelite missions spaced out along the Amazon between the Napo and the Río Negro, a distance of more than 1,000 miles, and the handful of Indians living in these stations had been thoroughly transformed: The

“native women [were] all clad in Britany linen,” and the Indians used “coffers with locks and keys, iron utensils, needles, knives, scissors, combs and a variety of little European articles.” When La Condamine and Maldonado reached the Río Negro, they found that slave traders, known as “redemption troops,” were scouring that river clean as well, every year advancing “farther into the country.” The Jesuit João Daniel estimated that the population along the Amazon and its main tributaries had declined to a thousandth of what it had been 200 years earlier. In his journey down the Amazon, La Condamine had revealed the wonders of a great wilderness and at the same time—somewhat unwittingly—borne witness to the tragic tale of a civilization lost.

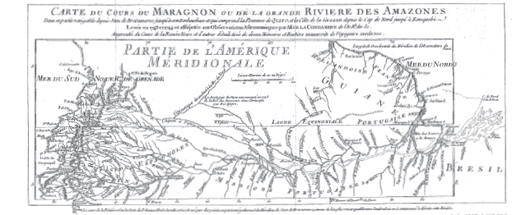

La Condamine’s map of the Amazon.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Relation abrégée d’un voyage fait dans l’intérieur de l’Amérique Méridionale

(1778)

.

L

A

C

ONDAMINE AND

M

ALDONADO

parted ways in Pará. Maldonado, mindful that the Portuguese had imprisoned Father Fritz as a spy, told the authorities in Pará that he was French, traveling on La Condamine’s passport, and on December 3, he sailed for Portugal. La Condamine traveled by sea canoe to Cayenne, and along the way, the trunk containing his cinchona saplings was swept overboard. In Cayenne, he repeated Richer’s 1672 experiments with the seconds pendulum, and then—fearful that if he traveled on a French boat, he might lose his cherished papers to English pirates—he traveled to Dutch Guiana in order to find passage to Europe on a ship sailing under the flag of the Netherlands. He departed on September 3, 1744, and while his trip across the Atlantic was not uneventful—pirates attacked the Dutch ship twice—he successfully arrived back in Paris on February 23, 1745, a full decade after he had left.

Initially, La Condamine did not receive the welcome he hoped for. Debate over the earth’s shape was fizzling to an end by this time. Not only had Maupertuis returned with his results many years earlier, but the academy had also recently remeasured a degree of arc in France, which had shown that the Cassinis’ earlier work had been in error. Voltaire even made fun of La Condamine with a witty put-down:

“In dull, distant places, you suffered to prove what Newton knew without having to move.”

Even so, the academy members understood the larger accomplishments of the mission. As La Condamine told his peers shortly after he returned, knowing that the earth bulged at the equator

“furnishes a new argument and demonstration of the rotation of the earth on its axis, a rotation that holds for the entire celestial system.” Their work at the equator, he added, “has put us on the path of even more important discoveries, such as the nature of the universal laws of gravity, the force that animates all heavenly bodies and which governs all the universe.”

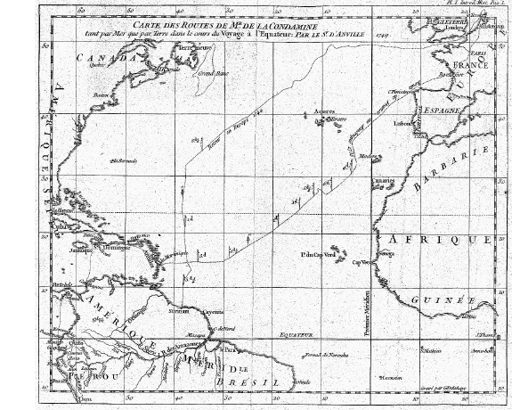

La Condamine’s map of his 10-year journey.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Relation abrégée d’un voyage fait dans l’intérieur de l’Amérique Méridionale

(1778)

.

Furthermore, this advance in physics was just the beginning of what had been achieved by the Peruvian mission. La Condamine’s study of the cinchona tree promised to help Europe improve its use of quinine as an antidote for malaria and other fevers. He had sent back samples of a useful new metal, platinum, and his writings on rubber were stirring imaginative thoughts on how to use it for manufacturing purposes. Europe now had a detailed map of the entire northern part of South America and a naturalist’s view of the Andes and the Amazon. Together these amounted to a grand achievement: The mission had been a transforming moment in the

development

of science, and it was Voltaire who understood this

best.

“By all appearances our wise men only added a few numbers to the science of the sky,” he wrote, “but the scope of their work was really much broader.” The mission to Peru, he said, was a “model for all scientific expeditions” to follow.

Title page of La Condamine’s account of the expedition.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur

(1751)

.

La Condamine’s skills as a writer also brought him a great deal of public adulation. He wrote a colorful account of his travels, complete with a blow-by-blow description of the war of the pyramids and Senièrgues’s murder. As his fame grew, science academies in London, Berlin, Saint Petersburg, and Bologna all made him an honorary member. The one sour note in this chorus of acclaim was sounded, oddly enough, by Bouguer. Long jealous of La

Condamine’s popularity, he published an account of their arc measurements in which he disparaged La Condamine’s talents as a scientist, suggesting that he had brought little more than energy to the project.

“Bouguer could not disguise his feelings of superiority as a mathematician over La Condamine,” observed one of their peers, Jacques Delille. He “felt that he should be the primary object of public affection.” Bouguer’s unflattering words set off a pointless quarrel that lasted for years, a dispute all the more difficult to comprehend, Delille wrote, because it was “between two men who for several years had slept in the same room, in the same tent, and often in the open air huddled under the same coat, and who in all this time publicly acknowledged a great respect for one another.”

Ulloa and Juan made an equally big splash in Europe upon their return. They had sailed from Callao, near Lima, on October 22, 1744, but on different boats and each with a copy of their papers, a precaution in case one of them did not return safely home. The two left from Callao on French frigates, and while Juan made it back with little difficulty, Ulloa’s ship was attacked by an English vessel, and he was taken to England as a prisoner. However, once the academicians of London understood who was in their prison at Portsmouth, Ulloa was released and named a fellow of the Royal Society of London, its members praising him as a “true caballero” and “man of merit.” This was a rare honor for a foreigner, and even more so for one who had arrived in England in shackles. In 1748, he and Juan became famous throughout Europe when they published a popular five-volume account of their travels,

Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

. Their book pulled back the curtain on South America and was translated into German, French, English, and Dutch, the Jesuit scholar Andres Burriel praising it as

“one of the best and most useful books that have been published in our tongue.”

Naturally, bits and pieces of this news filtered back to the others still in Peru. Maldonado was made a corresponding member of the Royal Society of London and of the French Academy of Sciences

for having traveled the Amazon with La Condamine, and his election made all of Riobamba proud.

*

But hearing this was bittersweet for Jean Godin and the others, a reminder that they had been forgotten. Of all the assistants, only one, Verguin, had managed to make it back to Europe by the end of 1748. Hugo had married a Quito woman and settled there, writing plaintively to La Condamine that he had

“no other wish but to find a way to return to France, to finish his days in his own country.” He subsequently disappeared; by 1748, nobody knew where he was. Morainville, meanwhile, had become the third member of the expedition to die. He had fallen from a scaffold while helping to build a church in Riobamba, a job he had taken to earn money to return home. As for Jussieu and Louis Godin, both had been told by the Quito Audiencia at the end of the expedition that they would not be allowed to leave. Jussieu’s medical skills were needed because a smallpox epidemic had erupted, and the audiencia was so insistent on this point that it promised to imprison anyone who tried to help him go. Louis Godin had been barred from departing because of his debts, and at the request of the Peruvian viceroy, he had taken a position as professor of mathematics at the University of San Marcos in Lima.

Their delayed departures had in turn led to greater heartache. The French Academy prohibited any member from taking an academic post in a foreign country, and Louis Godin’s letter explaining why he had done so never made it to Paris, for the ship carrying his letter was raided by pirates. The French Academy learned about his professorship through a third party and expelled him, thinking that he had voluntarily chosen to leave the service of France. Jussieu, meanwhile, had become broken in body and spirit. When he was finally allowed to leave Quito, he traveled to Lima to see Godin and then headed further south on a plant-hunting expedition, dedicated to his botany, but enveloped in a sadness

so profound, he wrote, that his

“heart [was] covering itself with a black veil.”

As for Jean, he was hatching a half-crazed plan to bring Isabel, who was pregnant for a fourth time, to France.

H

IS FATHER

’

S DEATH

was not the only reason that Jean and Isabel had decided that it was time to leave Riobamba. Events were brewing that suggested the good times for the colonial elite in the village might be coming to an end. Growing social unrest was making all the landowners nervous. The War of Jenkins’s Ear had forced Spain to greatly increase its military spending, and in order to raise that money, the Crown had hiked the duties and taxes that already so oppressed the Indian population. Bitter natives complained that colonial authorities wanted to tax the air they breathed. Some Indians had even taken up arms against their Spanish masters—there had been five revolts in the Andes since 1740. Equally troubling, the local economy was beginning to falter. Jean’s difficulty in collecting debts owed him was simply part of a larger malaise. After Britain sacked Porto Bello in 1740, Spain had shut down its fleet system for carrying goods to Peru and had begun allowing individual ships—including some non-Spanish vessels—to sail to any number of colonial ports. Many trading boats had started sailing around Cape Horn to Lima, loaded with cheap textiles from the mills of Europe, and this competition was driving more than a few obraje owners into bankruptcy.