The Making Of The British Army (49 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

For the moment the retreat continued. But the French commander-in-chief, the massive, imperturbable General Joseph Joffre, had not been idle. Despite the poor progress of the counter-offensive in Lorraine he was able to cobble together a new army (the 6th) to cover Paris, his efforts at personal liaison much aided by his being speeded along the roads of north-west France by Georges Boillot, the Peugeot racing team’s lead driver.

And, indeed, it was the petrol engine that now came to the rescue, first on 2 September, when a lone pilot on a reconnaissance flight from the Paris garrison brought the news to Joffre that von Kluck’s 1st Army was turning

east

rather than continuing south and west to envelop the

city, thereby presenting a flank into which the allies could attack.

154

And then the military governor of Paris, the wiry veteran General Gallieni, rounded up every taxi cab he could find and sent the garrison forward in comfort and the high spirits that go with clever improvisation and the prospect of turning the tables. But Joffre had to persuade the BEF to join in, and Lanrezac’s words before Mons still rankled with Sir John French, who the day before had been dissuaded from withdrawing the BEF from the fighting only through Kitchener’s personal intervention. His meeting with French was at first frosty, but then ‘Papa Joffre’ played to the heart: ‘Monsieur le maréchal, c’est la France qui vous supplie.’ Sir John French, reduced to tears, tried to reply but language failed him. Turning to his interpreter he said, ‘Dammit, I can’t explain. Tell him all that men can do, our fellows will do.’

In any case the BEF had had enough of retreating. They had twice done what the British army used to do so well in Wellington’s day – occupy a position and defy eviction – but it was now time to do what they had also done well for even longer, since Marlborough’s time: go to it with the bayonet.

The main weight of the counter-attack was to be in the valley of the Marne (indeed, the turning back of the seemingly unstoppable German advance on Paris would be dubbed ‘the Miracle on the Marne’). However, the BEF’s advance was at first hesitant, for Sir John French’s head had not quite caught up with his heart, although as the Germans began to give way before the wholly unexpected onslaught of three French armies Smith-Dorrien’s and Haig’s corps were able to increase the pressure too. By 13 September the Germans had fallen back to the River Aisne, with the allies snapping at their heels, though they were never quite able to turn harassing pursuit into rout. Then the swelteringly hot weather broke at last and the torrential rain swelled the rivers and streams which lay in the path of the BEF, the bridges blown by the retreating Germans who now dug in on the high ground north of the Aisne.

Many a gallantry medal was won by the BEF’s sappers and infantry as they threw assault bridges across the Aisne and attacked the heights

– but to no avail. The Germans had seized the best ground, and the allies were running out of steam. Indeed, the nature of the battle in north-west France was changing, as Sir John French noted in a letter to the King: ‘The spade will be as great a necessity as the rifle, and the heaviest types and calibres of artillery will be brought up on either side.’

But neither side was ready quite yet to concede that the war of manœuvre was finished: there remained the open flank – the gap between General Manoury’s improvised 6th Army, which Joffre had placed on the BEF’s left, and the sea. Both the allies and the Germans would now begin two months of increasingly desperate scrabbling to turn each other’s flank. But with mobility still determined by the marching pace of the infantry, the race for the flank succeeded only in drawing out the trench lines north across the uplands of the Somme, and on in front of the ancient city of Arras, and then down into the polder and sandy lowlands of Flanders – and eventually to the dunes at Nieuport (thereby preserving a symbolically important piece of Belgian sovereign territory after Antwerp eventually surrendered in October). On the way, the BEF would have the worst of its fighting so far, and a battle that would all but extinguish the old pre-war regular army, the men who had sailed for France only two months before.

Reinforcement had been continuous since those heady days in August. Regulars redeployed from both home defence and overseas garrisons, and volunteer units of the TF as well as British and Indian troops from the subcontinent, swelled the BEF to five corps – four of infantry (predominantly), including the Indian Corps, and one of cavalry. By the middle of October Sir John French had some 250,000 men at his disposal, a match at last for von Kluck’s army opposite him. And it looked as if he had at last found the German flank – at Ypres. Urged on by General Ferdinand Foch, whom Joffre had sent north to re-energize the fighting, French put the BEF on to the offensive along the Menin Road on 21 October. They soon ran into trouble, however, for under the forceful leadership of Erich von Falkenhayn, who had replaced the broken Moltke, the Germans had reinforced their right flank by bringing Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria’s 6th Army from Alsace-Lorraine, and had themselves gone on to the offensive.

A month’s hard fighting followed. In defence the BEF’s regiments held their ground with all the insolent resolution of Wellington’s men

at Waterloo. In the attack they went forward with the steady resolve of Raglan’s troops at the Alma – and assaulted with all the ferocity of the Peninsular infantry storming the walls of Badajoz. In innumerable local counter-attacks they threw themselves at the Germans with that same zeal to get to close quarters that King William’s bayonets had shown at Steenkirk. And it was ‘all hands to the pump’, the cavalry corps sending the horses to the rear and taking up their rifles to hold Messines Ridge south of Ypres. The first TF regiments were blooded too – the London Scottish, the first Territorials to go into action, losing half their strength in the process. And the Germans had their first sight of the turbans, pugarees and Gurkha pill-boxes of the Indian Corps; Sepoy Khudadad Khan of the Duke of Connaught’s Own Baluchi Regiment won the first ever Indian VC at Hollebeke on 31 October, when it looked as if the Germans might break the line. These were indeed desperate days, when individual soldiers in individual regiments made a difference. The whole BEF line was probably saved in fact by the 2nd Worcesters, the only troops left in front of Ypres as the Germans captured Gheluvelt on the Menin Road on that last morning in October; the battalion had already been reduced to 400 (less than 50 per cent of its embarkation strength in August), and lost another 200 retaking the vital ground.

On 11 November there was another crisis, when the 1st and 4th Brigades of the Prussian Guard attacked astride the Menin road, breaking through the defence line and getting to within 2 miles of the city. Only the bayonets of the 2nd Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and a scratch force of Grenadiers, Irish Guards and the Royal Munster Fusiliers were able to restore the situation – but at shattering cost, including the loss of the brigadier, Charles FitzClarence, who had won the VC at Mafeking.

The attack of the Prussian Guard, however, like that of the Garde Impériale at Waterloo, was the high-water mark of the German offensive at Ypres, and in the days that followed the fighting slackened. From now on, indeed, the armies went to ground – what was left of them, for while the Germans had fallen in droves, often shoulder to shoulder (and even singing), so too had the British. The BEF lost 58,000 officers and men in what would become known as the first battle of Ypres, and most of them were the irreplaceable regulars who could march all day, use cover and fire fifteen aimed rounds a minute. By Christmas in many battalions there were no more than a few dozen soldiers and a

single officer left who had been at Mons. The battles of late summer and autumn 1914 were the breaking of the ‘Old Contemptibles’, the old regular British army. For them the lights had indeed gone out. The army would have to be remade by Kitchener’s men. Meanwhile – until 1917, when by Kitchener’s calculations Britain’s full military potential could be reached – the fort would have to be held by Territorials and by troops cobbled together from every corner of the Empire.

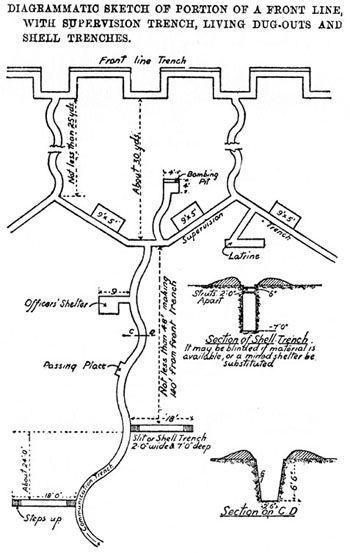

This sketch is from ‘Notes for Infantry Officers on Trench Warfare’ (1917).

And the ‘fort’ would be the trenches. From the North Sea to the Swiss border the armies on both sides were digging, wiring and sandbagging, sometimes within 100 yards of each other. A continuous line of trenches – continuous

lines

, indeed: fire trench, support trench, reserve trench, with communication trenches linking each – soon lay across the French countryside like giant railway tracks. For the most part, the Germans had the best of the ground – higher, for good observation, and drier, so that they could dig their shelters deep. When Kitchener’s New Armies were ready to go to France, they would have to face the problem of how to cross the ground between the lines – ‘no-man’s-land’ – before the Germans could come out of their holes with machine guns, and how then to break through the deep defensive belt into the open country beyond before the Germans could seal the breach with troops brought from reserve. And many hundreds of thousands of Kitchener’s men would die trying to find the answer.

1915–16

KITCHENER’S NEW ARMIES HAVE NO TRUE PARALLEL IN HISTORY. THE RESPONSE

to the call to arms was remarkable, and the mass improvisation no less astonishing. While some of the recruits were doubtless thankful for an excuse to exchange a life of hardship or tedium for one which promised excitement and a little local fame, the motive of the vast majority appears to have been simple patriotism – for ‘King and Country’ – or else a sense of local solidarity, of ‘mateship’. For at the same time that individual recruits were flocking to the army’s recruiting centres, Kitchener gave local grandees leave to raise battalions en bloc (often initially at their own expense) with the simple promise that those who enlisted together would be allowed to serve together.

The promise of serving together proved powerful. In Liverpool the earl of Derby, the great mover and shaker of the commercial northwest (and subsequently director-general of army recruiting), called on the office workers to form a battalion: ‘This should be a battalion of pals, a battalion in which friends from the same office will fight shoulder to shoulder for the honour of Britain and the credit of Liverpool.’ And so were born the ‘Pals’ battalions. But instead of one battalion, between 28 August (a Friday) and 3 September Liverpool raised

four

, the clerks of the White Star shipping company forming up as one platoon, those of Cunard as another, and so on through the

warehouses of the Mersey waterside, the cotton exchange, the banks and the insurance companies – men who knew each other better than their mothers knew them, and now doing what their mothers would never ordinarily have countenanced: going for a soldier – at least ‘for the duration’.

Across the Pennines in Barnsley two battalions of Pals were raised, officially designated the 13th and 14th (Service) Battalions, York and Lancaster Regiment (the prefix ‘Service’ – abbreviated from ‘General Service’, as opposed to ‘Home Service’ – was appended to all New Army battalions). Most of the recruits here were miners, many of whom had worked underground since they were 13 and so were not averse to the prospect of three square meals a day and work in the open air for a year or so. In the cities north of the border the response was the same. Glasgow raised three Pals battalions for the Highland Light Infantry, which were named after the institutions from which they had spontaneously sprung: Glasgow Tramways (15th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry), Glasgow Boys’ Brigade (16HLI) and Glasgow Commercials (17HLI). Newcastle boosted the Northumberland Fusiliers by two such institutional battalions – the Newcastle Commercials (16NF) and the Newcastle Railway Pals (17NF) – and by no fewer than twelve ‘tribal’ battalions: six of Tyneside Scottish and six of Tyneside Irish, forming two whole brigades. Perhaps the most exclusive-sounding of the Pals was the Stockbrokers’ Battalion (10th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers), and the most endearingly unmilitary (to modern ears, at least) the 21st Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment – the ‘Wool Textile Pioneers’. John Keegan in

The Face of Battle

(1976) writes: