The Making Of The British Army (48 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

I thought I should burst with inward gratification at the smartness of those gunners. They were really splendid, perfectly turned out, shining leather, flashing metal, beautiful horses, and the men absolutely unconcerned, disdaining to show the least surprise at or even interest in their strange surroundings … I said nothing, but stole a glance at the French officer who accompanied me and was satisfied, for he was rendered almost speechless by the sight of these fighting men. He had not believed such troops existed. He asked me if they were the Guard Artillery! [In fact there was no such thing.]

Soon after this we received a shock, and my French companion was further impressed, but in a way he did not much like, for we drove headlong into a most effective infantry trap. At a turn in the road we were suddenly faced by a barrier we had nearly run into, and found that without knowing it we had been covered for the last two hundred yards by cleverly concealed riflemen

belonging to the picquet. Had we been Germans nothing in the world could have saved us.

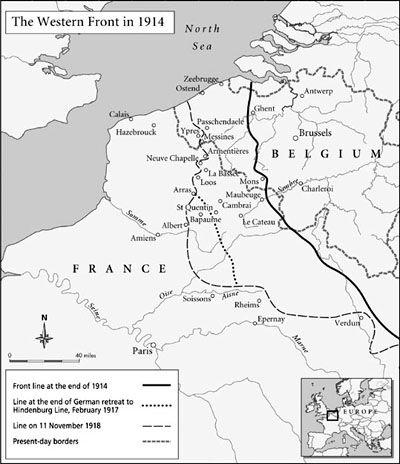

The following evening the BEF reached the line of the Mons-Condé Canal, where they halted, Sir John French having received reports from the Royal Flying Corps and the cavalry that there were Germans directly to his front, and from Spears that Lanrezac’s 5th Army was in severe trouble around Charleroi. He decided that to advance further was to risk being cut off, and so ordered his two corps commanders – Haig and General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien – to take up defensive positions along the canal. Next morning, Sunday, the advance guards of General Alexander von Kluck’s 1st Army clashed with Smith-Dorrien’s II Corps (3rd and 5th Divisions) as Haig’s I Corps (1st and 2nd Divisions) were still coming up on II Corps’ right. It was ‘encounter battle’ – fluid, confused, and still very much a place for cavalry: the 15th Hussars, reconnoitring east of Mons for the 3rd Division at first light, were cut up badly by rifle fire and shelling, and 22-year-old Corporal Charles Garforth began his run of three heroic actions that led to the award of the VC.

147

It would be many weeks yet before the lines solidified and the cavalry were sent to the rear.

The pressure on Smith-Dorrien’s II Corps increased throughout the day, and by evening they had pulled back to a second position just south of Mons. At about midnight French learned that Lanrezac’s 5th Army was withdrawing, and so he sent out orders for the BEF to do likewise. Haig’s corps, which had not been much engaged, was able to break clean without difficulty next morning, but II Corps had a much harder time of it: one of the rearguard battalions, the 2nd Cheshires, was surrounded, ran out of ammunition and had to surrender; and L Battery RHA, supporting 1st Cavalry Brigade, fired more rounds that day than it had during the whole of the Boer War (a few days later the battery was totally destroyed, its gunners winning three VCs in the process). The casualties mounted steadily, II Corps in all losing 2,000 men killed, wounded or missing.

But the fighting along the canal had inflicted far heavier casualties on the Germans, many of whose units, whatever their sophisticated tactical manuals said, attacked in column or shoulder to shoulder (it

was said that the reservists gained confidence from

das Tuchfühl –

the ‘touch of cloth’). The German novelist Walter Bloem, a 46-year-old reservist captain in the 12th Brandenburg Grenadiers, recorded how he spent the whole day trying to see the enemy, but felt only their rifle fire, his regiment losing almost all its officers and 500 men. It was not just the losses that hit hard but also the shock of finding themselves up against a more formidable enemy than the ‘contemptibly little’ one they had been expecting: ‘my proud, beautiful battalion … shot to pieces by the English, the English we laughed at’. It is always a severe blow to morale to discover that the enemy is better than had been rated, and makes for a double dose of wariness subsequently. Bloem’s commanding officer issued orders for the night, showing just what a shock it had been: ‘Watch the front very carefully, and send patrols at once up to the line of the canal,’ he told his company commanders. ‘If the English have the slightest suspicion of the condition we are in they will counterattack tonight, and that would be the last straw.’

148

Bloem was astonished when he learned next morning that ‘the English’ were withdrawing, and that his Brandenburgers were to advance. When they did they found more evidence of the BEF’s shocking capability – a sand-bagged machine-gun emplacement in a wood from which a devastating enfilade fire had thinned their ranks the day before: ‘Wonderful, as we marched on, how they had converted every house, every wall into a little fortress: the experience no doubt of old soldiers gained in a dozen colonial wars; possibly even some of the butchers of the Boers were among them.’ No doubt, but it lay, too, in a tradition reaching much further back – to the loop-holed walls of Hougoumont and the ‘little fortress’ of La Haye Sainte.

Indeed, II Corps’ commander, Smith-Dorrien, would now reach back even further, however unconsciously – to Sir John Moore and the retreat to Corunna. His men were dog-tired after the march up to Mons, the battle the following day along the canal and the fighting withdrawal over the next two in the stifling August heat. They had not been able to break clean, the Germans harrying them every mile of the retreat, and Smith-Dorrien feared for the cohesion of his corps.

On the evening of the twenty-fifth, with the 4th Division (which the war cabinet had belatedly agreed to send to France) detraining at Le Cateau 30 miles south-west of Mons and placed by French under

II Corps, Smith-Dorrien decided to stand and fight. He intended giving the Germans what he called a ‘smashing blow’ so that his corps could properly break clean. French neither approved nor forbade it, instead sending a half-hearted message that Smith-Dorrien must judge things for himself.

The twenty-sixth dawned even hotter after a rainy night, and the battle got off to a bad start on the extreme left flank where 4th Division were still taking up positions. They had had little rest in the cattle trucks bringing them up from Calais; they had then marched north to relieve 5th Division as rearguard and fought their way back again all through the night, so that by first light they wanted rest as badly as II Corps’ other two divisions. With them was 1st Battalion the King’s Own, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Dykes who had won the DSO as adjutant of the 2nd Battalion at Spion Kop. The searing experience of small-arms fire poured into the close-packed ranks of riflemen that day in South Africa appears to have failed him now, for he ordered the companies to pile arms, remove equipment and rest, despite being on a forward slope. The country was more open than the coal-mining landscape of Mons, but Dykes believed they were screened by French cavalry, although the battalion could clearly see the Lancashire Fusiliers digging in on the crest behind them on their left. At about six o’clock a party of horsemen appeared from the trees 1,000 yards ahead of the battalion, but Dykes took no notice, assuming them to be French. Soon after, a horse-drawn vehicle came out of the woods, and moments later a machine gun opened up in a long, raking burst which killed 83 men, including Dykes himself, and wounded 200.

149

Artillery accounted for another hundred in the scrambling minutes that followed, and those King’s Own who emerged unscathed were extricated only by the spirited support of the 1st Royal Warwicks, one of whose platoon commanders was Lieutenant Bernard Law Montgomery.

150

Nothing could have demonstrated better the new reality of war than this killing burst against one of the most experienced regiments in the army. If the Germans had had a rude shock at Mons, the BEF were now

having theirs at Le Cateau. But the shock would not demoralize them: the ‘experience of old soldiers gained in a dozen colonial wars’, which Bloem so admired, was also the experience of coping with setbacks and accepting casualties. The BEF was not only a well-trained army, it was a toughened one. Although the King’s Own had lost their commanding officer and half their fighting strength in a few minutes, they reorganized and fought throughout the day as doggedly as the rest of the brigade – just as the second battalion had done in South Africa after Spion Kop.

The fighting at Le Cateau intensified throughout the morning, but the Germans paid a heavy price for their gains, for Smith-Dorrien had chosen a position obliging them to advance down a long forward slope which gave his marksmen and gunners full opportunity to show their skill. Private F. W. Spicer of the 1st Bedfordshires (who would be commissioned and rise to lieutenant-colonel, such were the quality in the ranks of the BEF and the need for officers in Kitchener’s New Armies) wrote in his diary:

It must have been midday or later when the enemy infantry began to attack our immediate front. We had a real hour’s hard work firing our rifles. Luckily we had brought plenty of ammunition with us, and we needed it. Line after line of German infantry advanced only to be mowed down by our rifle and machine gun fire. The battery of the 15th Artillery Brigade in the dip of ground [close behind] did great execution. The enemy suffered such enormous losses that they were unable to force us from our positions, and themselves had to withdraw from our front for a time until they were reinforced.

But although II Corps was able to repel the Germans’ frontal attacks, soon after midday pressure on the right flank became too much, for a gap had opened up between Haig’s and Smith-Dorrien’s corps the day before while they were withdrawing to Le Cateau either side of the Forêt de Mormal. The 2nd Suffolks were cut off, their commanding officer was killed and the Germans called on them to surrender. They refused and the battle continued until they were surrounded and their ammunition exhausted, by which time all but 100 of the Suffolks’ 1,000 officers and men who had detrained at Maubeuge five days earlier had been killed, wounded or taken prisoner.

By now, however, Smith-Dorrien was confident that he had given the Germans enough of a smashing blow to be able to order his divisions

to start slipping away and putting some distance behind them. And indeed by nightfall he had been able to disengage, although the rearguard paid heavily, as did the artillery, for the guns had all fought forward with the infantry, exactly as they had at Waterloo, and when the horse teams came up to haul them out of action they were shot down in their hundreds. The Royal Artillery lost thirty-eight guns that day, more than in any action of the army’s 250-year history. It would be the beginning of the end for artillery firing over open sights: from now on they would seek cover and fire indirect, with the fall of shot adjusted by observation officers with field telephones and, much later, radio.

But although they had broken clean, Smith-Dorrien’s men were exhausted. Serjeant John McIlwain of the 2nd Connaught Rangers records how at

about 4 am our officers, who were wearied as ourselves, and apparently without orders, and in doubt what to do, led us back to the position of the night before. After some consultation we took up various positions in a shallow valley. Told to keep a sharp lookout for Uhlans [German lancers]. We appeared to be in some covering movement. No rations this day; seemed to be cut off from supplies. Slept again for an hour or so on a sloping road until 11 am. We retired to a field, were told we could ‘drum up’ as we had tea. I went to a nearby village to get bread. None to be had, but got a fine drink of milk and some pears. Upon the sound of heavy gunfire near at hand we were hastily formed up on the road.

McIlwain might have been writing the diary a hundred years earlier, for it has that same trusting, make-do attitude of the British soldier before Waterloo. They knew a much-vaunted army was bearing down on them, now as then, and yet they were unconcerned enough to go off foraging. Le Cateau was indeed the army’s biggest set-piece battle since Waterloo. And when at the end of the day’s fighting Sergeant McIlwain’s platoon joined back up with the rest of the battalion, he found that the casualty toll had been just as grievous: ‘By evening we mustered half-battalion strength. “C” had about half a company. Over the whole Major Sarsfield took command, the Adjutant, Captain Yeldham, was also present. Colonel Abercrombie and 400 or so others were captured by the Germans.’

The losses throughout the BEF had indeed been heavy: 7,812 men were accounted killed, wounded or taken prisoner, most of them from

II Corps, and for this reason Le Cateau, although celebrated as a British victory (and a name much favoured for post-war barracks), is still a controversial battle. Sir John French’s intense dislike of Smith-Dorrien had not helped.

151

Although he wrote in his despatches of his subordinate’s ‘rare and unusual coolness, intrepidity and determination’, privately he blamed Smith-Dorrien for disobeying orders, and believed the battle to have been both unnecessary and at the same time more costly than in fact it was.

152

From then on Smith-Dorrien was a marked man, and in May 1915 he was sent home. Or rather, sent ‘’ome’, for the news was given to him by the BEF’s chief of staff, Lieutenant-General Sir William (‘Wully’) Robertson, who had risen from the rank of private in the 16th Lancers (and would rise even further, to field marshal) and delighted in dropping his aitches to emphasize his origins.

153

And so the only man in the BEF other than Haig capable of taking over as commander-in-chief when French was himself relieved at the end of 1915 would be dismissed with a matter-of-fact ‘’Orace, you’re for ’ome.’