The Making Of The British Army (21 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

Howe was a capable soldier, and he knew the country. He had led the first troops up the Heights of Abraham at Quebec and had been with Amherst at the capture of Montreal. But the early bruising battle at Bunker Hill in June, where the Americans held their ground like seasoned troops, had shaken his confidence severely: ‘A dear-bought victory,’ wrote Major-General Henry Clinton, one of his commanders; ‘another such would have ruined us.’ After Bunker Hill, indeed, Howe became excessively cautious and reluctant to seek any direct confrontation. But he saw clearly that the rebellion was much more than London supposed. It was not the work of a minority of colonists who could be faced down easily by a local display of force (even if he had had the force). Begging for 20,000 more troops, he wrote to London that ‘with a less force … this war may be spun out until England will be heartily sick of it’.

With one of those exquisite twists of eighteenth-century irony, Howe’s letter landed on the desk of a man outstandingly ill-equipped to respond to it. For the Secretary of State for the America Department, the minister responsible for the higher direction of the war – the determination of strategy, the appointing of generals and the allocation of resources – was none other than Lord George Sackville, reinvented as

Lord George Germain. Despite the Minden court martial’s verdict that he was ‘unfit to serve His Majesty in any military capacity whatever’, the new King had taken him to his bosom, never having got on with his grandfather and so delighting in reversing his decisions.

Sackville’s views of the insurrection across the Atlantic, where he had never set foot, were straightforward, and set the tone for the ‘counter- insurgency’ campaign: ‘the rabble … ought not trouble themselves with politics and government, which they do not understand … these country clowns cannot whip us’.

With this underestimation of the threat, a commander-in-chief rapidly losing his nerve, and six to eight weeks’ sailing between the issue and receipt of reports and orders, the stage was set for tragedy. Sackville and the prime minister, Lord North, would proceed on the assumption that the American militias could not stand against British regulars, and that the war would be the same as that which they had recently fought in Europe. Marlborough would have wept.

Revolutionary America, 1777–83

THERE HAD NEVER BEEN A SIGHT LIKE IT: A BRITISH ARMY UTTERLY DEFEATED,

grounding arms and surrendering. And in the rotunda of the Capitol in Washington, reminding every United States legislator and visitor alike that independence was won by force of arms, not merely by declaration, there is a huge painting of the scene. Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne in full dress uniform gives up his sword to General Horatio Gates, who also wears full dress, but dark blue, the colour of the American regulars. Gates, however, is refusing to accept the sword, indicating that he will treat with Burgoyne as a gentleman, and inviting him into his marquee from which flies the Stars and Stripes. Gates’s officers, also clad in regular uniform, with not a racoon hat to be seen, observe the ceremonies with due gravity, while those in red coats appear bewildered and dejected. Burgoyne’s force had left Canada 10,000 strong; they had lost 4,000 in the following six months, and now the remaining 6,000 were prisoners of war – small numbers by continental European standards, but the shock of surrender was felt round the world, for Saratoga had brutally revealed the hopelessness of Sackville’s strategic assessment, as well as the dangerous weakness of the British military after the economies that had followed the Seven Years War. Indeed, Burgoyne’s defeat determined the ultimate outcome of the revolution, and thereby the course of history. What had happened?

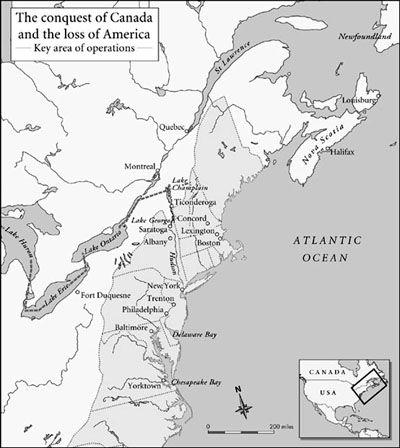

After Howe’s hesitant and inconsequential manœuvring of the previous year, in 1777 Sackville had devised a strategy to cut off New England, the seat of the rebellion, from the rest of the colonies. Burgoyne, commanding British forces in Canada, was to advance south via Lake Champlain and Lake George to the Hudson River and then to Albany. En route he was to be reinforced by 2,000 Canadian militiamen, American loyalists and Iroquois Indians under the experienced Brigadier-General Barrimore St Leger, who would march east into the colony from Canada along the Mohawk River. Meanwhile Howe, who as well as being commander-in-chief had personal command of the larger of the two armies in the colonies (in New York City), would march north, taking control of the lower Hudson, and join up with Burgoyne and St Leger in Albany. But for some reason never satisfactorily explained – afterwards the generals blamed Sackville, and he them – Howe instead moved against Philadelphia, seat of the Congress (which by now comprised delegates of all thirteen colonies and was the ‘brain’ of the revolution). And he did so by sea, which was a sound enough move in the context of his own plan, but meant that he was in no position to come to Burgoyne’s aid once the latter’s advance began to unravel. In a perfect example of strategic futility, Howe succeeded in taking Philadelphia – but not before the Congress had slipped away.

Burgoyne’s army, consisting of 3,000 British regulars, 4,000 Brunswick mercenaries, and 1,000 Canadians and Indians, had been tramping south for a month when Howe left New York. They retook Fort Ticonderoga, the main American base along the chain of lakes, on 6 July (it had been captured by Benedict Arnold in a brilliant action in May 1775), but unfortunately not with the defenders inside. The next day at Hubbardton they caught up with the Americans in a bloody clash from which the rebels finally broke and ran – at which point Burgoyne made a bad decision. Why is not entirely clear, but he had a deal of self-regard that could tip over into swaggering over-confidence. Instead of taking the most direct route to Albany, by boat via Lake George and then, after the relatively short portage to Fort Edward, down the Hudson River, he struck out overland east of the lake via Fort Anne to harry the fugitives and bring them to battle. But the forests of Vermont and upper New York were not the plains of Germany or Flanders: the terrain hindered his own movement and greatly favoured the defenders.

Destroying rebel forces en route was not essential to Burgoyne’s

mission of linking up with Howe to cut off New England. It would be a bonus, but only if achieved without detriment to his primary object. In any case, he had secured Fort Ticonderoga, and once he had joined up with Howe the rebels would be hopelessly outnumbered and restricted in their options. In other words, there was no need to fight. Some fifty years later the Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz would enumerate the principles of war, the first of which is selection and maintenance of the aim: that is, commanders correctly identifying the object of military action and then directing all effort towards achieving it, a concept the ancients understood well enough. Howe’s extraordinary diversion to Philadelphia may have been the more spectacular breach of the principle, but Burgoyne’s was just as culpable, and just as calamitous.

His army now made slow progress in the wilderness, allowing the Americans to recover. The rebels chopped down trees to block what tracks there were – heavy work, but heavier still for the pursuers, who had to clear each obstacle to get the guns and waggons past. It took until 1 August to get to the Hudson at Fort Edward, by which time Burgoyne was running out of supplies. And here he received a letter from Howe telling him of the change of plan.

A further week passed while Burgoyne took stock of the situation, his supplies critically low. In the end he decided to send 1,000 of his Germans and Indians to forage east towards Bennington, Vermont. This proved disastrous, both militarily and in propaganda terms. The Vermont militia had already been alerted, and all but a handful of Burgoyne’s detachment were killed or captured. Yet even if his men had been able to requisition supplies in a regular fashion, in exchange for cash or promissory notes, commandeering food and animal fodder at this time of year was a depredation which the colonists could only have resented. In fact, so heavy-handed – brutal, even – was the foraging, that loyalists across New England began changing allegiance, while Congress exploited the ‘atrocities’ throughout the colonies.

Burgoyne had already had to leave behind almost a fifth of his force to secure Fort Ticonderoga. Now, after Bennington, his Indian scouts, on whom he relied heavily in the forests, began deserting him. And to make matters worse, although he would not hear of it until the end of the month, St Leger’s force, his only source of reinforcements, turned back at Fort Stanwix 80 miles west on the Mohawk.

In contrast with both Howe’s and Burgoyne’s misconceived moves,

the American commander-in-chief General George Washington had acted with a sure strategic touch. He knew little of Burgoyne’s object and progress, and even less about what Howe intended to do after embarking his army at New York, for Washington had no navy to shadow the fleet. His crucial decision, therefore – whether to send reinforcements north to counter Burgoyne or south to meet Howe (if indeed Howe was headed south) – rested on military logic rather than on definite intelligence. A weaker general would have delayed until Howe’s object became clear, by which time it would have been too late to intervene decisively either way, but Washington recognized that the greatest danger was a junction between Howe’s and Burgoyne’s armies, and decided therefore to march against Burgoyne to prevent it. For good measure, too, he sent ahead his most pugnacious colonel, the legendary (and later infamous) Benedict Arnold, with 500 sharpshooters of the 11th Virginia Regiment, some of his best troops, and called out every man of the New England militia.

But who would lead this northern army? Congress, on hearing that Fort Ticonderoga had been abandoned without a fight, had sacked General Philip Schuyler from his command of the Northern Department – one congressman echoing Voltaire: ‘we shall never hold a post until we shoot a general’ – and now appointed the gentlemanly General Gates in his stead. It was risky: Gates was a former British officer (although so were many), and his experience was limited. Nevertheless he quickly recognized the strength of the position that Schuyler had been preparing at Bemis Heights on the Hudson, 20 miles downstream from Fort Edward, and sent every man he could muster there – 15,000 regulars and militia – to block the British advance.

At Fort Edward, learning of the strengthening American defences, Burgoyne calculated that he had three options. He could try to take Bemis Heights, although the Americans outnumbered him two to one. He could cross to the east bank of the Hudson, under fire, and try to bypass the position, although this would expose his flank. Or he could acknowledge that the strategic situation had changed radically, and return to Canada. But turning back was not in Burgoyne’s character. And crossing the Hudson River – risking a fluid battle against superior numbers in country he did not know – would be hazardous in the extreme. The course that most suited him (he had made his name leading a bold attack on a Spanish fortress during the Seven Years War),

would be to attack Bemis Heights; there, at least, he knew the enemy’s position and intention. And so he chose to attack.

Having moved up the bulk of his force by the middle of September, and after a preliminary reconnaissance, on the nineteenth Burgoyne began the assault with a right-flanking approach through land belonging to a loyalist, John Freeman, whose farm the Americans had failed to picket. By mischance, however, that very morning Benedict Arnold had finally persuaded Gates, despite their mutual loathing, to allow him to send troops to picket the farm, denying Burgoyne therefore his only real chance of success.