The Lying Stones of Marrakech (23 page)

Read The Lying Stones of Marrakech Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Lamarck therefore began his campaign of reform by raiding Vermes and gradually adding the extracted groups as novel phyla in his newly named category

of invertebrates. In his first course of 1793, he had already expanded the Linnaean duality to a ladder of progress with five rungsâmollusks, insects, worms, echinoderms, and polyps (corals and jellyfish)âby liberating three new phyla from the wastebucket of Vermes.

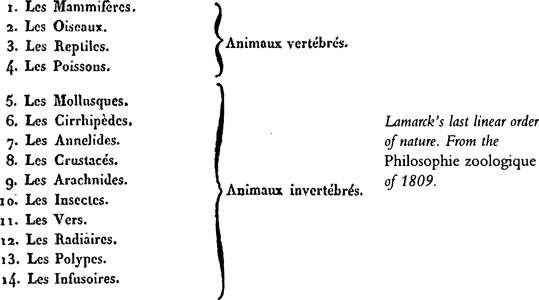

This reform accelerated in 1795, when Georges Cuvier arrived and began to study invertebrates as well. The two men collaborated in friendship at firstâ and they surely operated as one mind on the key issue of dismembering Vermes. Thus, Lamarck continued to add phyla in almost every annual course of lectures, extracting most new groups from Vermes, but some from the overblown Linnaean Insecta as well. In year 7 (1799), he established the Crustacea (for marine arthropods, including crabs, shrimp, and lobsters), and in year 8 (1800) the Arachnida (for spiders and scorpions). Lamarck's invertebrate classification of 1801 therefore featured a growing ladder of progress, now bearing seven rungs. In 1809, he presented a purely linear sequence of progress for the last time in his most famous book,

Philosophic zoologique

. His tall and rigid ladder now included fourteen rungs, as he added the four traditional groups of vertebrates atop a list of invertebrate phyla that had just reached double digits (see accompanying chart direcdy reproduced from the 1809 edition).

So far, Lamarck had done nothing to inspire any reconsideration of the evolutionary views first presented in his

Floréal

address of 1800. His taxonomie reforms, in this sense, had been entirely conventional in adding weight and strength to his original views. The

Floréal

statement had contrasted a linear force leading to progress in major groups with a lateral force causing local adaptation in particular lineages. Lamarck's ladder included only seven groups in the

Floréal

address. By 1809, he had doubled the length while preserving the same stricdy linear formâthus strengthening his central contrast between two forces by granting the linear impetus a gready expanded field for its inexorably exceptionless operation.

Lamarck's last linear order of nature. From the Philisophie zoologique of 1809

But if Lamarck's first reform of Linnaeusâthe expansion of groups into a longer linear seriesâhad conserved and strengthened his original concept of evolution, he now embarked upon a second reform, destined (though he surely had no inkling at the outset) to yield the opposite effect of forcing a fundamental change in his view of life. He had, heretofore, only extracted misaligned groups from Linnaeus's original Vermes. He now needed to consider the core of Vermes itselfâand to determine whether waste and rot existed at the foundation as well.

“Worms,” in our vernacular understanding, are defined both broadly and negatively (unfortunate criteria guaranteeing inevitable trouble down the road) as soft-bodied, bilaterally symmetrical animals, roughly cylindrical in shape and lacking appendages or prominent sense organs. By these criteria, both earthworms and tapeworms fill the bill. For nearly ten years, Lamarck did not seriously challenge this core definition.

But he could not permanendy ignore the glaring problem, recognized but usually swept under the rug by naturalists, that this broad vernacular category seemed to include at least two kinds of organisms bearing litde relationship beyond a superficial and overt similarity of external form. On the one hand, a prominent group of free-living creaturesâearthworms and their alliesâbuilt bodies composed of rings or segments, and also developed internal organs of substantial complexity, including nerve tubes, blood vessels, and a digestive tract. But another assemblage of largely parasitic creaturesâtapeworms and their alliesâgrew virtually no discretely recognizable internal organs at all, and therefore seemed much “lower” than earthworms and their kin under any concept of an organic scale of complexity. Would the heart of Vermes therefore need to be dismembered as well?

This problem had already been worrying Lamarck when he published the

Floréal

address in his 1801 compendium on invertebrate anatomyâbut he was not yet ready to impose a formal divorce upon the two basic groups of “worms.” Either standard of definition, taken by itselfâdifferent anatomies or disparate environmentsâmight not offer sufficient impetus for thoughts about taxonomie separation. But the two criteria conspired perfecdy together in the remaining Vermes: the earthworm group possessed complex anatomy

and

lived freely in the outside world; the tapeworm group maintained maximal simplicity among mobile animals

and

lived almost exclusively within the bodies of other creatures.

Lamarck therefore opted for an intermediary solution. He would not yet dismember Vermes, but he would establish two subdivisions

within

the class:

vers externes

(external worms) for earthworms and their allies, and

vers intestins

(internal worms) for tapeworms and their relatives. He stressed the simple anatomy of the parasitic subgroup, and defended their new name as a spur to further study, while arguing that knowledge remained insufficient to advocate a deeper separation:

It is very important to know them [the internal worms], and this name wall facilitate their study. But aside from this motive, I also believe that such a division is the most natural⦠because the internal worms are much more imperfect and simply organized than the other worms. Nevertheless, we know so little about their origin that we cannot yet make them a separate order.

At this point, the crucial incident occurred that sparked Lamarck to an irrevocable and cascading reassessment of his evolutionary views. He attended Cuvier's lecture during the winter of 1801â2 (year 10 of the revolutionary calendar), and became convinced, by his colleague's elegant data on the anatomy of external worms, that the extensive anatomical differences between his two subdivisions could not permit their continued residence in the same class. He would, after all, have to split the heart of Vermes. Therefore, in his next course, in the spring of 1802, Lamarck formally established the class Annelida for the external worms (retaining Vermes for the internal worms alone), and then separated the two classes widely by placing his new annelids above insects in linear complexity, while leaving the internal worms near the bottom of the ladder, well below insects.

Lamarck formally acknowledged Cuvier's spur when he wrote a history of his successive changes in classifying invertebrates for the

Philosophic zoologique

of 1809:

Mr. Cuvier discovered the existence of arterial and venous vessels in distinct animals that had been confounded with other very differendy organized animals under the name of worms. I soon used this new fact to perfect my classification; therefore, I established the class of annelids in my course for year 10 (1802).

The handwritten note and drawing in Lamarck's 1801 book, discussed and reproduced earlier in this essay, tells much the same storyâbut what a contrast,

in both intellectual and emotional intrigue, between a sober memory written long after an inspiration, and the inky evidence of the moment of enlightenment itself!

But this tale should now be raising a puzzle in the minds of readers. Why am I making such a fuss about this particular taxonomie changeâthe final division of Vermes into a highly ranked group of annelids and a primitive class of internal worms? In what way does this alteration differ from any other previously discussed? In all cases, Lamarck subdivided Linnaeus's class Vermes and established new phyla in his favored linear seriesâthus reinforcing his view of evolution as built by contrasting forces of linear progress and lateral adaptation. Wasn't he just following the same procedure in extracting annelids and placing them on a new rung of his ladder? So it might seemâat first. But Lamarck was too smart, and too honorable, to ignore a logical problem direcdy and inevitably instigated by this particular division of wormsâand the proper solution broke his system.

At first, Lamarck did treat the extraction of annelids as just another addition to his constandy improving linear series. But as the years passed, he became more and more bothered by an acute problem, evoked by an inherent conflict between this particular taxonomie decision and the precise logic of his overarching system. Lamarck had ranked the phylum Vermes, now restricted to the internal worms alone, just above a group that he named

radiaires

âactually (by modern understanding) a false amalgam of jellyfishes from the coelenterate phylum and sea urchins and their relatives from the echinoderm phylum. Worms had to rank above radiates because bilateral symmetry and directional motion trump radial symmetry and an attached (or not very mobile) lifestyleâ at least in conventional views about ladders of progress (which, of course, use mobile and bilaterally symmetrical humans as an ultimate standard). But the parasitic internal worms also lack the two most important organ systemsâ nerve ganglia and cords, and circulatory vesselsâthat virtually define complexity on the traditional ladder. Yet echinoderms within the “lower” radiate phylum develop both nervous and circulatory systems. (These organisms circulate sea water rather than blood, but they do run their fluids through tubes.)

If the primary “force that tends incessandy to complicate organization” truly works in a universal and exceptionless manner, then how can such an inconsistent situation arise? If the force be general, then any given group must stand fully higher or lower than any other. A group cannot be higher for some features, but lower for others. Taxonomie experts cannot pick and choose. He who lives by the line must die by the line.

This problem did not arise so long as annelids remained in the class of worms. Lamarck, after all, had never argued that each genus of a higher group must rank above all members of a lower group in every bodily part. He only claimed that the “principal masses” of organic design must run in pure linear order. Individual genera may degenerate or adapt to less complex environments in various partsâbut so long as some genera display the higher conformation in all features, then the entire group retains its status. In this case, so long as annelids remained in the group, then many worms possessed organ systems more complex than any comparable part in any lower groupâand the entire class of worms could retain its unambiguous position above radiates and other primitive forms. But with the division of worms and the banishment of complex annelids, Lamarck now faced the logical dilemma of a coherent group (the internal parasitic worms alone) higher than radiates in some key features but lower in others. The pure march of nature's progressâthe keystone of Lamarck's entire systemâhad been fractured.

Lamarck struggled with this problem for several years. He stuck to the line of progress in 1802, and againâfor the last time, and in a particularly uncompromising manner that must, in retrospect, represent a last hurrah before the fallâin the first volume of his seminal work,

Philosophic zoologique

, of 1809. But honesty eventually trumped hope. Just before publication, Lamarck appended a short chapter of “additions” to volume two of

Philosophie zoologique

. He now, if only tentatively, floated a new scheme that would resolve his problem with worms, but would also unravel his precious linear system.

Lamarck had long argued that life began with the spontaneous generation of “infusorians” (single-celled animals) in ponds. But suppose that spontaneous generation occurs twice, and in two distinct environmentsâin the external world for a lineage beginning with infusorians, and inside the bodies of other creatures for a second lineage beginning with internal worms? Lamarck therefore wrote that “worms seem to form one initial lineage in the scale of animals, just as, evidently, the infusorians form the other branch.”

Lamarck then faced the problem of allocating the higher groups. To which of the two great lines.does each belong? He presented his preliminary thoughts in a chartâperhaps the first evolutionary branching diagram ever published in the history of biologyâthat directly contradicted his previous image of a single ladder. (Compare this figure with the version presented earlier in this essay, taken from volume one of the same 1809 work.) Lamarck begins (at the top, contrary to current conventions) with two lines, labeled

“infusoires”

(single-celled animals) and

“vers”

(worms). He then inserts light

dots to suggest possible allocations of the higher phyla to the two lines. The logical problem that broke his system has now been solvedâfor the

radiaires

(radiate animals), standing below worms in some features, but above in others, now rank in an entirely separate series, directly following an infusorian beginning.

When mental floodgates open, the tide of reform must sweep to other locales. Once he had admitted branching and separation at all, Lamarck could hardly avoid the temptation to apply this new scheme to other old problems. Therefore, he also suggested some substantial branching at the end of his array. He had always been bothered by the conventional summit of reptiles to birds to mammals, for birds seemed just different from, rather than inferior to, mammals. Lamarck therefore proposed (and drew on his revolutionary chart) that reptiles branched at the end of the series, one line passing from turtles to birds

(oiseaux)

to

monotrèmes

(platypuses, which Lamarck now considers as separate from mammals), the other from crocodiles to marine mammals (labeled

m. amphibies)

to terrestrial mammals. Finally, and still in the new spirit, he even posited a threefold branching in the transition to terrestrial mammals, leading to separate lines for whales

(m. cétacés)

, hoofed animals

(m. ongulés)

, and mammals with nails

(m. onguiculés)

, including carnivores, rodents, and primates (including humans).