The Lying Stones of Marrakech (20 page)

Read The Lying Stones of Marrakech Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

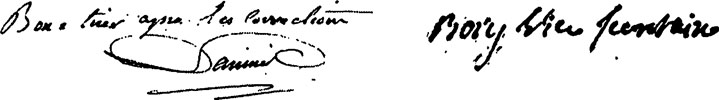

Lavoisier's signature (left) on one of his geological plates

.

Lavoisier's own flourishes enhance the visual beauty of the plates that express the intellectual brilliance of his one foray into my field of geologyâall signed in the year of the revolution that he greeted with such hope (and such willingness to work for its ideals); the revolution that eventually repaid his dedication in the most cruel of all possible ways. But now I hold a tiny little bit, only a symbol really, of Lavoisier's continuing physical presence in my professional world.

The skein of human continuity must often become this tenuous across the centuries (hanging by a thread, in the old cliché), but the circle remains unbroken if I can touch the ink of Lavoisier's own name, written by his own hand. A candle of light, nurtured by the oxygen of his greatest discovery, never burns out if-we cherish the intellectual heritage of such unfractured filiation across the ages. We may also wish to contemplate the genuine physical thread of nucleic acid that ties each of us to the common bacterial ancestor of all living creatures, born on Lavoisier's

ancienne terre

more than 3.5 billion years agoâ and never since disrupted, not for one moment, not for one generation. Such a legacy must be worth preserving from all the guillotines of our folly.

A Tree Grows

in Paris: Lamarck's

Division of Worms and

Revision of Nature

I. T

HE

M

AKING AND

B

REAKING OF A

R

EPUTATION

ON THE TWENTY-FIRST DAY OF THE AUSPICIOUSLY

named month of

Floréal

(flowering), in the spring of year 8 on the French revolutionary calendar (1800 to the rest of the Western world), the former

chevalier

(knight) but now

citoyen

(citizen) Lamarck delivered the opening lecture for his annual course on zoology at the Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle in Parisâand changed the science of biology forever by presenting the first public account of his theory of evolution. Lamarck then published this short discourse in 1801 as the first part of his treatise on invertebrate animals

(Système des animaux sans vertebres)

.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744â1829) had enjoyed a distinguished career in botany when, just short of his fiftieth birthday, he became professor of insects and worms at the Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle, newly constituted by the revolutionary government in 1793. Lamarck would later coin the term

invertebrate

for his charges. (He also introduced the word

biology

for the entire discipline in 1802.) But his original tide followed Linnaeus's designation of all nonverte-brated animals as either insects or worms, a Procrustean scheme that Lamarck would soon alter. Lamarck had been an avid shell collector and student of mollusks (then classified within Linnaeus's large and heterogeneous category of Vermes, or worms)âqualifications deemed sufficient for his change of subject.

Lamarck fully repaid the confidence invested in his general biological abilities by publishing distinguished works in the taxonomy of invertebrates throughout the remainder of his career, culminating in the seven volumes of his comprehensive

Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres

(Natural history of invertebrate animals), published between 1815 and 1822. At the same time, he constandy refined and expanded his evolutionary views, extending his introductory discourse of 1800 into a first full book in 1802

(Recherches sur l'organisation des corps vivans

, or Researches on the organization of living beings), to his magnum opus and most famous work of 1809, the two-volume

Philosophic zoologique

(Zoological philosophy), to a final statement in the long opening section, published in 1815, of hisgreat treatise on invertebrates.

The outlines of such a career might seem to imply continuing growth of prestige, from the initial flowering to a full bloom of celebrated seniority. But Lamarck's reputation suffered a spectacular collapse, even during his own lifetime, and he died lonely, blind, and impoverished. The complex reasons for his reverses include the usual panoply of changing fashions, powerful enemies, and self-inflicted wounds based on flaws of character (in his case, primarily an overweening self-assurance that led him to ignore or underestimate the weaknesses in some of his own arguments, or the skills of his adversaries). Most promi-nently, his favored style of scienceâthe construction of grand and comprehensive theories following an approach that the French call

l'esprit de système

(the spirit of system building)âbecame notoriously unpopular following the rise of a hard-nosed empiricist ethos in early-nineteenth-century geology and natural history.

In one of the great injustices of our conventional history, Lamarck's disfavor has persisted to our times, and most people still know him only as the foil to Darwin's greatnessâas the man who invented a silly theory about giraffes stretching their necks to reach the leaves on tall trees, and then passing the fruits of their efforts to their offspring by “inheritance of acquired characters,” otherwise

known as the hypothesis of “use and disuse,” in contrast with Darwin's proper theory of natural selection and survival of the fittest.

Indeed, the usually genial Darwin had few kind words for his French predecessor. In letters to his friends, Darwin dismissed Lamarck as an idle speculator with a nonsensical theory. In 1844, he wrote to the botanist J. D. Hooker on the dearth of evolutionary thinking (before his own ideas about natural selection): “With respect to books on the subject, I do not know of any systematical ones except Lamarck's, which is veritable rubbish.” To his guru, the geologist Charles Lyell (who had accurately described Lamarck's system for English readers in the second volume of his

Principles of Geology

, published in 1832), Darwin wrote in 1859, just after publishing

The Origin of Species:

“You often allude to Lamarck's work; I do not know what you think about it, but it appeared to me extremely poor; I got not a fact or idea from it.”

But these later and private statements did Lamarck no practical ill. Far more harmfully, and virtually setting an “official” judgment from that time forward, his eminent colleague Georges Cuvierâthe brilliant biologist, savvy statesman, distinguished man of letters, and Lamarck's younger and antievolutionary fellow professor at the Muséumâused his established role as writer

of éloges

(obituary notices) for deceased colleagues to compose a cruel masterpiece in the genre of “damning with faint praise”âa document that fixed and destroyed Lamarck's reputation. Cuvier began with cloying praise, and then described his need to criticize as a sad necessity:

In sketching the life of one of our most celebrated naturalists, we have conceived it to be our duty, while bestowing the commendation they deserve on the great and useful works which science owes to him, likewise to give prominence to such of his productions in which too great indulgence of a lively imagination had led to results of a more questionable kind, and to indicate, as far as we can, the cause or, if it may be so expressed, the genealogy of his deviations.

Cuvier then proceeded to downplay Lamarck's considerable contributions to anatomy and taxonomy, and to excoriate his senior colleague for fatuous speculation about the comprehensive nature of reality. He especially ridiculed Lamarck's evolutionary ideas by contrasting a caricature of his own construction with the sober approach of proper empiricism:

These [evolutionary] principles once admitted, it will easily be perceived that nothing is wanting but time and circumstances to enable

a monad or a polypus gradually and indifferently to transform themselves into a frog, a stork, or an elephantâ¦. A system established on such foundations may amuse the imagination of a poet; a metaphysician may derive from it an entirely new series of systems; but it cannot for a moment bear the examination of anyone who has dissected a hand ⦠or even a feather.

Cuvier's

éloge

reeks with exaggeration and unjust ridicule, especially toward a colleague ineluctably denied the right of responseâthe reason, after all, for our venerable motto,

de mortuis nil nisi bonum

(“say only good of the dead”). But Cuvier did base his disdain on a legitimate substrate, for Lamarck's writing certainly displays a tendency to grandiosity in comprehensive pronouncement, combined with frequent refusal to honor, or even to consider, alternative views with strong empirical support.

L'esprit de système

, the propensity for constructing complete and overarching explanations based on general and exceptionless principles, may apply to some corners of reality, but this approach works especially poorly in the maximally complex world of natural history. Lamarck did feel drawn toward this style of system building, and he showed no eagerness to acknowledge exceptions or to change his guiding precepts. But the rigid and dogmatic Lamarck of Cuvier's caricature can only be regarded as a great injustice, for the man himself did maintain appropriate flexibility before nature's richness, and did eventually alter the central premises of his theory when his own data on the anatomy of invertebrate animals could no longer sustain his original view.

This fundamental changeâfrom a linear to a branching system of classification for the basic groups, or phyla, of animalsâhas been well documented in standard sources of modern scholarship about Lamarck (principally in Richard W. Burkhardt,Jr.'s

The Spirit of System: Lamarck and Evolutionary Biology

, Harvard University Press, 1977; and Pietro Corsi's

The Age of Lamarck

, University of California Press, 1988). But the story of Lamarck's journey remains incomplete, for both the initiating incident and the final statement have been missing from the recordâthe beginning, because Lamarck noted his first insight as a handwritten insertion, heretofore unpublished, in his own copy of his first printed statement about evolution (the

al

address of 1800, recycled as the preface to his 1801 book on invertebrate anatomy); and the ending, because his final book of 1820,

Système analytique des connaissances positives de l'homme

(Analytical system of positive knowledge about man), has been viewed only as an obscure swan song about psychology, a rare book even more rarely consulted (despite a

fascinating section containing a crucial and novel wrinkle upon Lamarck's continually changing views about the classification of animals). Stories deprived of both beginnings and endings cannot satisfy our urges for fullness or completionâand I am grateful for this opportunity to supply these terminal anchors.

II. L

AMARCK'S

T

HEORY AND

O

UR

M

ISREADINGS

Lamarck's original evolutionary systemâthe logical, pure, and exceptionless scheme that nature's intransigent complexity later forced him to abandonâfeatured a division of causes into two independent sets responsible for progress and diversity respectively. (Scholars generally refer to this model as the “two-factor theory.”) On the one hand, a “force that tends incessantly to complicate organization”

(la force qui tend sans cesse à composer l'organisation)

leads evolution linearly upward, beginning with spontaneous generation of “infusorians” (single-celled animals) from chemical precursors, and moving on toward human intelligence.

But Lamarck recognized that the riotous diversity of living organisms could not be ordered into a neat and simple sequence of linear advanceâfor what could come direcdy before or after such marvels of adaptation as long-necked giraffes, moles without sight, flatfishes with both eyes on one side of the body, snakes with forked tongues, or birds with webbed feet? Lamarck therefore advocated linearity only for the “principal masses,” or major anatomical designs of life's basic phyla. Thus, he envisioned a linear sequence mounting, in perfect progressive regularity, from infusorian to jellyfish to worm to insect to mollusk to vertebrate. He then depicted the special adaptations of particular lineages as lateral deviations from this main sequence.

These special adaptations originate by the second set of causes, labeled by Lamarck as “the influence of circumstances”

(l;'influence des circonstances)

. Ironically, this second (and subsidiary) set has descended through later history as the exclusive “Lamarckism” of modern textbooks and anti-Darwinian iconoclasts (while the more important first set of linearizing forces has been forgotten). For this second setâbased on change of habits as a spur to adaptation in new environmental circumstancesâinvokes the familiar (and false) doctrines now called “Lamarckism”: the “inheritance of acquired characters” and the principle of “use and disuse.”

Lamarck invented nothing original in citing these principles of inheritance, for both doctrines represented the “folk wisdom” of his time (despite their later disproof in the new world of Darwin and Mendel). Thus, the giraffe stretches its neck throughout life to reach higher leaves on acacia trees, and the

shorebird extends its legs to remain above the rising waters. This sustained effort leads to longer necks or legsâand these rewards of hard work then descend to offspring in the form of altered heredity (the inheritance of acquired characters, either enhanced by use, as in these cases, or lost by disuse, as in eyeless moles or blind fishes living in perpetually dark caves).