The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (8 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

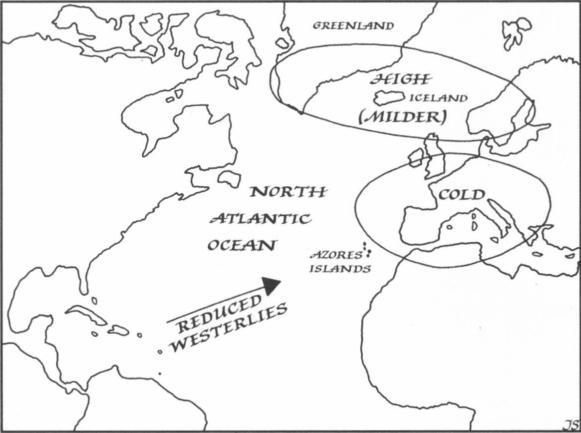

The chaotic atmosphere over the North Atlantic plays a major role in

the NAO's unpredictable behavior. So do the mild waters of the Gulf

Stream, which flow northeast off North America and then become the

North Atlantic current, bringing warm water to the British Isles and adjacent coasts as far north as Iceland and Norway. The warmer surface waters

of the north flush regularly, sinking toward the bottom, carrying atmospheric gases and excess salt. Two major downwelling sites are known, one

just north of Iceland, the other in the Labrador Sea southwest of Greenland. At both these locations, vast quantities of heavier, salt-laden water

sink far below the surface. Deep subsurface currents then carry the salt southward. So much salt sinks in the northern seas that a vast heat pump

forms, caused by the constant influx of warmer water, which heats the

ocean as much as 30 percent beyond the warmth provided by direct sunlight in the north. What happens if the flushing fails? The pump slows

down, the warm North Atlantic current weakens, and temperatures fall

rapidly in northwestern Europe. When downwelling resumes, the current

accelerates and temperatures climb again. The effect is like a switch, triggered by the interaction of atmosphere and ocean. For example, in the

early 1990s, the Labrador Sea experienced vigorous downwelling, which

gave Europe mild winters. In 1995/96, the NAO index changed abruptly

from high to low, bringing a cold winter in its wake.

Greenland above effect

The NAO has affected European climate for thousands of years. By

piecing together information from tree rings, ice cores, historical records,

and modern-day meteorological observations we now have a record of the

North Atlantic Oscillation going back to at least 1675. Low NAO indices

seem to coincide with known cold snaps in the late seventeenth century.

Over the past two centuries, NAO extremes have produced memorable

weather like the very cold winters of Victorian England in the 1880s. An other low index cycle in the 1940s enveloped Europe in savage cold as

Hitler invaded Russia. The 1950s were somewhat kinder, but the 1960s

brought the coldest winters since the 1880s. Over the past quartercentury, high NAO indices have brought the most pronounced anomalies

ever recorded and warmed the Northern Hemisphere significantly, perhaps as a result of humanly caused global warming.

For many centuries, Europe's weather has been at the mercy of capricious swings of the NAO Index and of downwelling changes in the Arctic. We do not know what causes high and low indices, nor can we yet

predict the sudden reversals that trigger traumatic extremes. But we can

be certain that the NAO was a major player in the unpredictable, often

extremely cold, highly varied weather that descended on Europe after

1300.

In the thirteenth century, Greenland and Iceland experienced increasing

cold. Sea ice spread southward around Greenland and in the northernmost Atlantic, creating difficulties for Norse ships sailing from Iceland as

early as 1203. Unusual cold brought early frosts and crop failures to

Poland and the Russian plains in 1215, when famine caused people to sell

their children and eat pine bark. During the thirteenth century, some

Alpine glaciers advanced for the first time in centuries, destroying irrigation channels in high mountain valleys and overrunning larch forests.

While colder temperatures afflicted the north, Europe as a whole benefited from the change. The downturn of temperatures in the Arctic

caused a persistent trough of low pressure over Greenland and enduring

ridges of high pressure over northwestern Europe. A period of unusually

warm, mostly dry summers between 1284 and 1311, in which May frosts

were virtually unknown, encouraged many farmers to experiment with

vineyards in England. After the turn of the fourteenth century, however,

the weather turned unpredictable.

The year 1309/10 may have been a "Greenland above" year. The dry

and exceptionally cold winter made the Thames ice over and disrupted

shipping from the Baltic Sea to the English Channel. An anonymous

chronicler wrote,

In the same year at the feast of the Lord's Nativity, a great frost and ice was

massed together in the Thames and elsewhere, so that poor people were

oppressed by the frost, and bread wrapped in straw or other covering was

frozen and could not be eaten unless it was warmed: and such masses of

encrusted ice were on the Thames that men took their way thereon from

Greenhithe in Southark, and from Westminster, into London; and it lasted

so long that the people indulged in dancing in the midst of it near a certain fire made on the same, and hunted a hare with dogs in the midst of

the Thames.I

By 1312, the NAO Index was high, the Atlantic storm track shifted southward, and winters were mild again. Three years later, the rains began in

earnest.

The deluge began in 1315, seven weeks after Easter. "During this season [spring 1315] it rained most marvellously and for so long," wrote a

contemporary observer, Jean Desnouelles. Across northern Europe,

sheets of rain spread in waves over the sodden countryside, dripping

from thatched eaves, flowing in endless rivulets down muddy country

lanes. Wrote chronicler Bernardo Guidonis: "Exceedingly great rains descended from the heavens, and they made huge and deep mud-pools on

the land." Freshly plowed fields turned into shallow lakes. City streets

and narrow alleys became jostling, slippery quagmires. June passed, then

July with little break in the weather. Only occasionally did a watery sun

break through the clouds, before the rain started again. "Throughout

nearly all of May, July, and August, the rains did not cease," complained

one writer.z An unseasonably cold August became an equally chilly September. Such corn and oats as survived were beaten down to the ground,

heavy with moisture, the ears still soft and unripened. Hay lay flat in the

fields. Oxen stood knee deep in thick mud under sheltering trees, their

heads turned away from the rain. Dykes were washed away, royal manors

inundated. In central Europe, floods swept away entire villages, drowning hundreds at a time. Deep erosion gullies tore through hillside fields

where shallow clay soils could not absorb the endless water. Harvests had

been less than usual in previous years, causing prices to rise, but that of

1315 was a disaster. The author of the Chronicle of Malmesbury wondered, like many others, if divine vengeance had come upon the land:

"Therefore is the anger of the Lord kindled against his people, and he hash stretched forth his hand against them, and hath smitten them."3

Tree rings from northern Ireland show that 1315 was a year of extraordinary growth for oak trees.

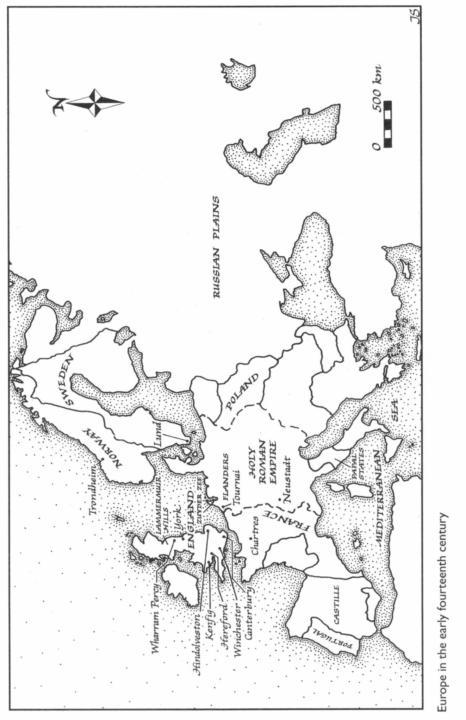

Europe was a continent of constant turmoil and minor wars, of endless

killings, raids, and military expeditions. Many conflicts stemmed from

succession disputes and personal rivalries, from sheer greed and reckless

ambition. The wars continued whatever the weather, in blazing sunshine

or torrential rain, armies feeding off villages, leaving empty granaries and

despoiled crops in their train. War merely increased the suffering of the

peasants, who lived close enough to the edge as it was. But the rains of

1315 stopped military campaigning in its tracks.

Trade and geography made Flanders one of the leading commercial

centers of fourteenth-century Europe. Italian merchant bankers and

moneylenders made their northern headquarters here, attracted by the

great wealth of the Flemish weaving industry. Technically a fief of France,

the country and its prosperous towns were more closely tied to England,

whose wool formed the cloth woven across the North Sea. The quality

and fine colors of Flemish fabrics were prized throughout Europe and as

far afield as Constantinople, creating prosperity but a volatile political situation. Both England and France vied for control of the region. While

the Flemish nobility kept French political interests and cultural ties dominant, the merchants and working classes favored England out of self-interest. In 1302, Flemish workers had risen in rebellion against their

wealthy masters. The flower of French knighthood, riding north to crush

the rebellion, had fallen victim to the swampy terrain, crisscrossed with

canals, where bowmen and pikemen could pick off horsemen like helpless fish. Seven hundred knights perished in the Battle of Courtai and the

defeat was not avenged for a quarter-century. The inevitable retaliation

might have come much earlier had not the rain of 1315 intervened.

In early August of that year, French king Louis X planned a military

campaign into Flanders, to isolate the rebellious Flemings from their

North Sea ports and lucrative export trade. His invasion force was poised

at the border before the Flemish army, ready to advance in the heavy rain.

But as the French cavalry trotted onto the saturated plain, their horses

sank into the ground up to their saddle girths. Wagons bogged down in

the mire so deeply that even seven horses could not move them. The infantry stood knee-deep in boggy fields and shivered in their rain-flooded tents. Food ran short, so Louis X retreated ignominiously. The thankful

Flemings wondered if the floods were a divine miracle. Their thankfulness did not last long, for famine soon proved more deadly than the

French.

The catastrophic rains affected an enormous area of northern Europe,

from Ireland to Germany and north into Scandinavia. Incessant rain

drenched farmlands long cleared of woods or reclaimed from marsh by

countless small villages. The farmers had plowed heavy soils with long

furrows, creating fields that absorbed many millimeters of rain without

serious drainage problems. Now they became muddy wildernesses, the

crops flattened where they grew. Clayey subsoils became so waterlogged

in many areas that the fertility of the topsoil was reduced drastically for

years afterward.

As rural populations grew during the thirteenth century, many communities had moved onto lighter, often sandy soils, more marginal farming land that was incapable of absorbing sustained rainfall. Deep erosion

gullies channeled running water through ravaged fields, leaving little

more than patches of cultivable land. In parts of southern Yorkshire in

northern England, thousands of acres of arable land lost their thin topsoil

to deep gullies, leaving the underlying rock exposed. As much as half the

arable land vanished in some places. Inevitably, crop yields plummeted.

Such grain as could be harvested was soft and had to be dried before it

could be ground into flour. The cold weather and torrential rains of late

summer 1315 prevented thousands of hectares of cereals from ripening

fully. Fall plantings of wheat and rye failed completely. Hay could not be

cured properly.

Hunger began within months. "There began a dearness of wheat.

... From day to day the price increased," lamented a chronicler in Flanders.4 By Christmas 1315, many communities throughout northwestern

Europe were already desperate.

Few people understood how extensive the famine was until pilgrims,

traders, and government messengers brought tales of similar misfortune

from all parts. "The whole world was troubled," wrote a chronicler at

Salzburg, which lay at the southern margins of the affected region.5 King

Edward II of England attempted to impose price controls on livestock,

but without success. After the hunger grew worse, he tried again, placing

restrictions on the manufacture of ale and other products made from grain. The king urged his bishops to exhort hoarders to offer their surplus

grain for sale "with efficacious words" and also offered incentives for the

importation of grain. At a time when no one had enough to eat, none of

these measures worked.