The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (4 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

-Geoffrey Chaucer, Canterbury Tales

And what a wonder! Some knights who were sitting on a magnificently outfitted horse gave the horse and their weapons away

for cheap wine; and they did so because they were so terribly

hungry.

A German chronicler of 1315

Major historical and climatic events, 950 to 1500

Anonymous, Hafgerdinga Lay

("The Lay of the Breakers')

he fog lies close to the oily, heaving water, swirling gently as a bitterly

he fog lies close to the oily, heaving water, swirling gently as a bitterly

cold air wafts in from the north. You sit gazing at a featureless world, sails

slatting helplessly. Water drips from the rigging. No horizon, no boundary between sea and sky: only the gray-shrouded bow points the way

ahead. The compass tells you the boat is still pointing west, barely moving through the icy chill. This fog can hug the water for days, hiding icebergs and the signs of rapidly forming pack ice. Or a few hours later, a

cold northeaster can fill in and sweep away the murk, blowing out of a

brilliantly blue sky. Then the horizon is as hard as a salt-encrusted knife,

the sea a deep blue frothing with white caps. Running easily under reduced sail, you sight snow-clad peaks far on the western horizon a halfday's run ahead-if the wind holds. As land approaches, the peaks cloud

over, the wind drops, small ice floes dot the now-calm ocean. The wise

mariner heaves to and waits for clearer weather and a breeze, lest ice block

the way and crush the ship to matchwood.

Icebergs move haphazardly across the northern seas. Pack ice floes undulate in broken rows in the endless ocean swell. Far to the north, a ribbon of gray-white light shimmers above the horizon, the ice-blink of solid

pack ice, the frontier of the Arctic world. To sail near the pack is to skirt

the barrier between a familiar universe and oblivion. A brilliant clarity of

land and sky fills you with keen awareness, with fear of the unknown.

For as long as Europeans can remember, the frozen bastions of the

north have hovered on the margins of their world, a fearsome, unknown

realm nurturing fantastic tales of terrible beasts and grotesque landscapes.

The boreal oceans were a source of piercing winds, vicious storms and

unimaginably cold winters with the ability to kill. At first, only a few Irish

monks and the hardy Norse dared sail to the fringes of the ice. King Harald Hardrade of Norway and England is said to have explored "the expanse of the Northern Ocean" with a fleet of ships in about A.D. 1040,

"beyond the limits of land" to a point so far north that he reached pack

ice up to three meters thick. He wrote: "There lay before our eyes at

length the darksome bounds of a failing world."' But by then, his fellow

Norse had already ventured far over northern seas, to Iceland, Greenland

and beyond. They had done so during some of the warmest summers of

the previous 8,000 years.

I have sailed but rarely in the far north, but the experience, the sheer

unpredictability of the weather, I find frightening. In the morning, your

boat courses along under full sail in a moderate sea with unlimited visibility. You take off your foul-weather gear and bask in the bright sun with,

perhaps, only one sweater on. By noon, the sky is gray, the wind up to 25

knots and rising, a line of dense fog to windward. The freshening breeze

cuts to the skin and you huddle in your windproof foulies. By dusk you

are hove-to, storm jib aback, main with three reefs, rising and falling to a

howling gale. You lie in the darkening warmth belowdecks, listening to

the endless shrieking of the southwester in the rigging, poised for disaster,

vainly waiting for the lesser notes of a dying storm. A day later, no trace

remains of the previous night's gale, but the still, gray water seems colder,

about to ice over.

Only the toughest amateur sailors venture into Arctic waters in small

craft, and then only when equipped with all the electronic wizardry of the

industrial age. They rely on weather faxes, satellite images of ice condi tions, and constant radio forecasts. Even then, constantly changing ice

conditions around Iceland and Greenland, and in the Davis Strait and

along the Labrador coast, can alter your voyage plans in hours or cause

you to spend days at sea searching for ice-free waters. In 1991, for example, ice along the Labrador coast was the worst of the twentieth century,

making coastal voyages to the north in small craft impossible. Voyaging

in the north depends on ice conditions and, when they are severe, small

boat skippers stay on land. Electronics can tell you where you are and

provide almost embarrassing amounts of information about what lies

ahead and around you. But they are no substitute for sea sense, an intimate knowledge of the moody northern seas acquired over years of ocean

sailing in small boats, which you encounter from time to time in truly

great mariners, especially those who navigate close to the ocean.

The Norse had such a sense. They kept their sailing lore to themselves

and passed their learning from family to family, father to son, from one

generation to the next. Their maritime knowledge was never written

down but memorized and refined by constant use. Norse navigators lived

in intimate association with winds and waves, watching sea and sky,

sighting high glaciers from afar by the characteristic ice-blink that reflects

from them, predicting ice conditions from years of experience navigating

near the pack. Every Norse skipper learned the currents that set ships off

course or carried them on their way, the seasonal migrations of birds and

sea mammals, the signs from sea and sky of impending bad weather, fog,

or ice. Their bodies moved with swell and wind waves, detecting seemingly insignificant changes through their feet. The Norse were tough,

hard-nosed seamen who combined bold opportunism with utterly realistic caution, a constant search for new trading opportunities with an abiding curiosity about what lay over the horizon. Always their curiosity was

tempered with careful observations of currents, wind patterns, and icefree passages that were preserved for generations as family secrets.

The Norse had enough to eat far from land. Their ancestors had

learned centuries before how to catch cod in enormous numbers from

open boats. They gutted and split the fish, then hung them by the thousands to dry in the frosty northern air until they lost most of their weight

and became easily stored, woodlike planks. Cod became the Norse hardtack, broken off and chewed calmly in the roughest seas. It was no coinci dence Norse voyagers passed from Norway to Iceland, Greenland and

North America, along the range of the Atlantic cod. Cod and the Norse

were inextricably entwined.

The explorations of the Norse, otherwise known as Vikings or "Northmen," were a product of overpopulation, short growing seasons, and

meager soils in remote Scandinavian fjords. Each summer, young "rowmen" left in their long ships in search of plunder, trading opportunities,

and adventure. During the seventh century, they crossed the stormy

North Sea with impressive confidence, raided towns and villages in eastern Britain, ransacked isolated Christian settlements, and returned home

each winter laden with booty. Gradually, they expanded the tentacles of

Norse contacts and trade over huge areas of the north. Norsemen also

traveled far east, down the Vistula, Dnieper, and Volga rivers to the Black

and Caspian seas, besieged Constantinople more than once and founded

cities from Kiev to Dublin.

The tempo of their activity picked up after 800. More raiding led, inevitably, to permanent overseas settlements, like the Danish Viking camp

at the mouth of the Seine in northern France, where a great army repeatedly looted defenseless cities. Danish attackers captured Rouen and

Nantes and penetrated as far south as the Balearic Islands, Provence, and

Tuscany. Marauding Danes invaded England in 851 and overran much of

the eastern part of the country. By 866, much of England was under the

Danelaw. Meanwhile, the Norwegian Vikings occupied the Orkney and

Shetland Islands, then the Hebrides off northwestern Scotland. By 874,

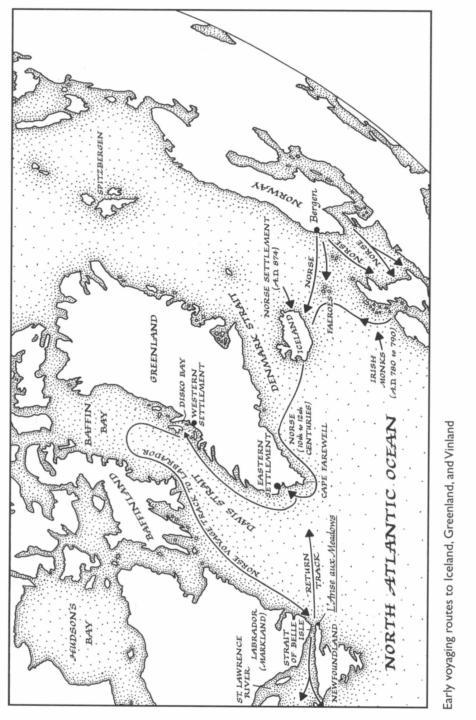

Norse colonists had taken advantage of favorable ice conditions in northern seas and settled permanently in Iceland, at the threshold of the Arctic.

The heyday of the Norse, which lasted roughly from A.D. 800 to about

1200, was not only a byproduct of such social factors as technology, overpopulation and opportunism. Their great conquests and explorations

took place during a period of unusually mild and stable weather in northern Europe called the Medieval Warm Period-some of the warmest four

centuries of the previous 8,000 years. The warmer conditions affected

much of Europe and parts of North America, but just how global a phenomenon the Warm Period was is a matter for debate. The historical consequences of the warmer centuries were momentous in the north. Be tween 800 and 1200, warmer air and sea surface temperatures led to less

pack ice than in earlier and later centuries. Ice conditions between

Labrador and Iceland were unusually favorable for serious voyaging.