The Life of Lee (21 page)

Authors: Lee Evans

Alas, whatever ‘it’ was, it would have to wait. I thought, ‘It may never happen.’ But there was no doubt that my fleeting encounter with the experience of being in front of an audience planted something in my head. It thrilled me like nothing else. I’d crossed a line. I didn’t know if it would ever come round again, but if it did, I’d be much better prepared the next time.

One thing was certain. I had changed and I knew that I was no longer destined to be a failure. If Mrs Taylor had been there that night, I would have blown her away.

19. The Art School Rebel

The band had kept my over-active head busy for a while, but now it was time to get real, as they say. I had left school at sixteen with a tiny pea for a brain and no qualifications other than the basic teenage trait of growing a face full of inflamed acne the size of which could be seen from space and a huge headful of fuzzy hair which a woolly mammoth would look at enviously and say, ‘Wow!’

All I had to show for my time at school was an O level in art, a subject I loved and was reasonably good at, so it looked as though the only prospect for me was to … if perhaps I could indulge myself for a moment, to artistically connect … to dig deep inside my soul and collaborate. With the end of the frigging dole queue.

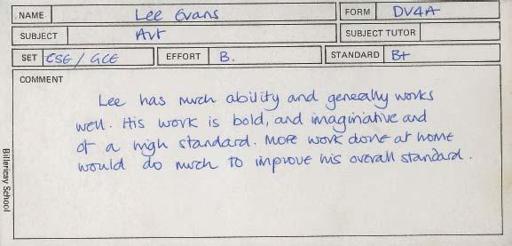

My art report – not too bad.

Margaret Thatcher was at the helm and driving us all mad. She was laying people off with a king-sized trowel and selling Britain off like it was a bring-and-buy sale. The country was experiencing a depression more gloomy than the Christmas Day episode of

EastEnders

. Mass unemployment reigned – jobs were definitely thin on the ground – and Norman Tebbit was telling us to get on our bikes. If I could have afforded one, I would have done.

I had no discernible talents apart from a good eye for drawing and painting – it was only the one eye, but it was a good one. Meanwhile, my school friends occupied

themselves with fighting, smoking, dating and then shagging their hands. They say it was the growth of the thumb and the ability to grip objects that propelled man from his ancestral ape relative into the sophisticated race we are today. Need I explain what perpetuated that growth? The date is 4000

BC

. We hear the echoes of frustration from a small cave entrance and just inside, lit by the flames of a burning fire, we see a hairy chunk of a man slapping himself in the groin area. ‘That’s nice … but if I could only grip it!’

Anyway, while my mates were putting their newly formed thumbs to good use, I was at home, busy creating stuff. Painting, drawing, modelling, that sort of thing. So by the time I left school, I’d managed to accumulate quite a body of work that I could take along to show the guy wearing a polo neck who was going to interview me at Thurrock College of Art and Design.

Art wasn’t something I was ever intending to do, but I eventually discovered it was the only option I had. Plus, I had become pretty competent at it, so I thought, ‘Why not? I’ve got nothing to lose.’

On the way to the interview, sitting on the bus clutching my huge art folder packed with my paintings, I really did feel that I was wasting my time. They didn’t let people like me into art college. I was too rough around the edges. Art college was for the floppy-haired Hush-Puppy mob. You know, the ones that slope around all day wearing baggy jumpers and scruffy jeans; the ones that if you told one of them to piss off, they would simply tilt their head with interest, bring one arm across their diaphragm to support the elbow of their other arm so they could wave

some pungent French cigarette inches from their lips and say in a pretentious turd-bag accent, ‘Yeaaah? When, like, you say “piss owff”, in what way do you actually mean “piss owff”?’ The sort of people who go home early as they have to spend the evening stroking their beards.

Well, that’s exactly how I turned out after six months. Yep, I was a fully fledged, beard-stroking twat who wore floppy jumpers, had bushy hair, wore odd-coloured socks and talked as if I needed everything to be somehow profound and meaningful. I had, as they say, had the operation. I was a bona fide art student.

When I first entered the art department of the huge college for my interview, I was immediately struck by the sheer array of art. The white-painted walls of the studio were filled with all types of work by the students, all at different stages of development. Some pieces hung around the walls, others sat there with bits missing, half finished. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. This, I said to myself, is me, this is what I want to do.

I lumbered, mollified, across the studio and was beckoned over by a softly spoken hippy type, a good-looking man with long wavy blond hair and deep blue eyes, sitting at a large table. I unzipped my folder apathetically and laid my paintings out across the table before the man, who, it emerged, was Sam Benjamin, the head tutor conducting the interviews that day.

I sat and waited for his reaction, never making full eye contact. I just hunched over, staring at the floor and wringing my hands so tightly my knuckles kept going white as the blood was forced out of them. I expected

him to say something disparaging. I’d made the mistake of showing some of my paintings to friends once, and they didn’t get them at all. ‘What is it?’ they would whine. ‘It doesn’t look like anything I know.’

Plus, I was very self-conscious about the fact that I might not look very ‘arty’. It had always been assumed on the council estate in Bristol and by the new friends I’d found in Billericay that art was something for the knobs and not us. I know it sounds ridiculous, but that’s how it was. The only way the kids I knew expressed themselves was through their fists. I should know, I’d been beaten up by some of the best punch-up artists around. That was why I decided to speak as little as possible to Mr Benjamin, assuming that as soon as I opened my mouth he would immediately put me in a certain, unflattering pigeonhole.

So I just looked down and waited, but to my surprise Mr Benjamin’s complaints never came. I momentarily flicked a glance up towards him. My attitude was softening – Mr Benjamin had a gentle way about him. He was a Jesus lookalike, with a very relaxed manner. He sat there cross-legged, caressing his well-trimmed, greying beard with his thin, delicate fingers, gazing intently with no particular hurry about him, contemplating the pictures spread out across the table. Slowly he raised his head to speak. Because he had looked so deep in thought, it made what he was about to say all the more important. I bent forward to listen.

He spoke in a calm, almost whispering voice. ‘This one here …’ He leaned over to point at a portrait I’d painted of my mum. It was one of my favourites but, of

course, I assumed he wouldn’t like it – that’s why he’d picked it out. Whenever I painted, I always approached it with energy and excitement. I would set about the canvas with a real verve, constantly changing brushes and colours over the whole piece. For the particular work Mr Benjamin had chosen, I remembered I’d used a whole range of different hues, emphasizing my mum’s beautiful, warm green eyes with blues, pinks, aquamarines, purples and turquoises. Mr Benjamin continued, ‘Your use of colour …’

‘Oh?’ I shrugged. ‘Everybody always says that about my paintings. There’s too much colour and that’s why it doesn’t look how it’s meant to.’ I thought he was about to say the same.

‘Yes, but only an idiot would think that, right?’ Mr Benjamin interjected.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, I can see that with your use of colour, you’re painting what you see. That’s important. Who cares what others think? I don’t. It’s about risk, right? I can see what you’re doing, I can see it, Lee.’

My jaw dropped. I was astonished. Blimey, I thought, either this bloke gets it, or any moment now he’s going to burst out laughing, say he was joking and send me packing. But he didn’t. He just stood there, helped me pack up my paintings and said simply: ‘I’ll let you know formally in a couple of days. The clock-watchers who run this place force us to do all this paperwork lark to make it official. But I can tell you now, I love your work, Lee, and really hope you’ll come and study with us.’

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I was glued to the

seat – no one ever got my paintings! ‘What?’ I asked, trying hard to suppress my incredulity. ‘You don’t think it’s a bit mental?’

‘Yep!’ he chuckled. ‘That’s why I like it!’

From that day on, I was bowled over by the openness and impartiality Mr Benjamin showed towards me. He seemed not to care at all about how I looked or the way I sounded – to him, none of that mattered. I got the impression the only thing that really mattered to him was what I had to give as an artist. He looked at it simply as a contribution, another idea, a way to reach a path to somewhere else. I could have entered the room on a space hopper in a Kojak cap, blowing ‘Who loves ya baby?’ on the bombardon and he wouldn’t have given a rat’s arse. How you actually don’t give a rat’s arse is something I have never really understood, but that’s a discussion for another day: ‘Hello, here is a rat, but the bit you ain’t getting is right there at the back.’ Anyway, what Mr Benjamin cared about much more was what I was trying to say through my art.

I began attending art college full-time. I hated the early mornings – still half-asleep, I’d crawl on to the bus at the stop in Billericay with my humungously large art folder. That was always a pain: whenever it was windy, you’d see me in the street looking like a man who was trying to parasail on dry land without a board. I’d shoot up the road, desperately trying to control the huge, flat, black case that threatened at any moment to whisk me into the air and away.

If it wasn’t that, I’d be struggling to manoeuvre it up

the aisle of the packed, steamy, morning bus. It always had an atmosphere of heavy drudgery. Its oh-no-another-day-at-work passengers all had zero patience, especially when nudged or poked by a passing duffel coat with fuzzy hair holding an oversized briefcase.

As I heaved and huffed – with great physical effort – up the aisle of the bus to the nearest vacant seat, my art folder would usually attract attention from some of the different crowds of workers. At that moment, I would inevitably become the morning’s entertainment for some lunkhead at the back. ‘Someone run over your briefcase with a steamroller, mate?’ some weasel face would cry out. That was a real crowd-pleaser, eliciting great gales of laughter from the packed sardine-like top deck of desperately grey passengers. ‘Here he comes, the incredible shrinking man.’ Funny! Yeah, but not every freaking day.

As the two-hour journey went on and the bus got closer to the college, the early-bird passengers would all eventually get off, gradually to be replaced by the second crowd of morning travellers. They were the art students who eventually filled the bus and turned it into what could only be described as a freak show. They were the complete opposite of those who had been on the bus earlier. It would now became an entirely different journey, as the vehicle filled with punks with huge spiky hair, Mods and young girls dressed up as their idol, Adam Ant, a massive hit with students at the time. There were others sporting wedge cuts and wearing jodhpurs like the pop group Haircut One Hundred, and the couple who got on every morning all done up like Dave Sylvian from the band Japan. I wondered how this lot ever got out of the

door in the morning, with the amount of garb and make-up they were all wearing. It must have been like getting ready for panto season, but every single day.

The bus would arrive outside the college and offload its morning menagerie of oddballs and misfits. An exotically dressed crowd, it looked like the circus had hit town. We would all enter the college, walking down the long corridor to the art department. This would lead us past the various other departments. First up, our parade would trigger the usual morning barrage of catcalls from all the testosterone-fuelled lads in the engineering department. Dressed in oily, these-prove-I’m-not-a-poof dungarees, they stood around next to their huge manly lathes, sniggering at us. ‘Look at them!’ they would sneer at us as we went by. ‘Lazy bastards!’

Then we would pass the catering department where a few of the students would inevitably stand on the other side of the glass in aprons and white trilbies, pointing and hurling taunts at us. ‘Benders! Bleeding weirdos!’

I kept my head down and carried on walking. Sporting only a duffel coat, Hush Puppies and bushy hair, I was able to blend in and not draw too much attention to myself. The abuse was aimed at the ones who were wearing make-up and decidedly different clothing.

I had a deep sense of admiration for the way they would stick passionately to their beliefs, always adhering to an unyielding and non-conformist dress sense. When they received the attention of the more macho students, these alternative types would shout back, thumbing their noses and barking back in return, like some mad gang who had just jumped out of a

Mad Max

movie. ‘Piss off,

you boring, conventional tosspots.’ I saw it as a badge of honour to be associated with these defiantly individualistic art students. I liked the fact that they viewed it as their duty to stand out from the crowd.